This article is published here with permission from Air & Space Magazine and includes editorial comments and corrections. The original article appeared in September 2011 issue.

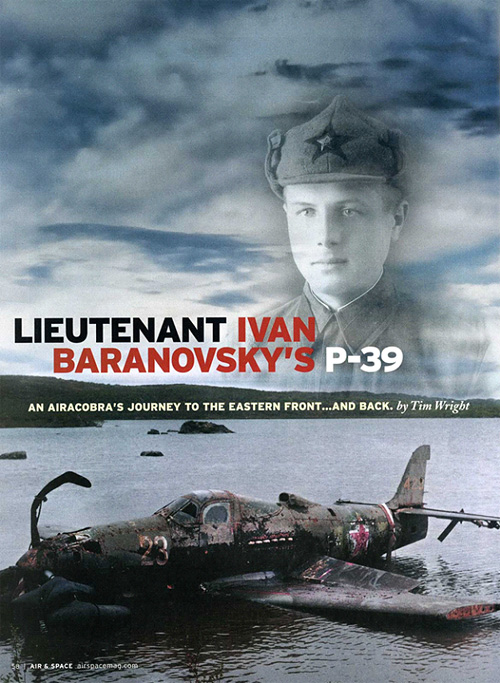

Most of the warbirds on view around the country today never made it into combat. This one did. I’m looking up at the ruined fuselage of a Bell P-39Q Airacobra, suspended from the ceiling of a work room at the Niagara Aerospace Museum in Buffalo, New York. Scattered about the space in the old Bell Aircraft factory where this very airplane was built are its wings, engine, and various tools for taking it apart. The underside fuselage panels are so badly damaged that they will be removed and replaced with new ones. The panels weren’t damaged from bullets, although the P-39 had been shot at plenty of times. They were battered during the fighter’s last landing, when 22-year-old Lieutenant Ivan Baranovsky, a combat veteran with seven victories, put it down on a frozen lake during a flight over the Soviet Union on November 19, 1944 [Lt. Baranovsky did not have seven victories. Between 21 June and 9 August his regiment, the 773 IAP (Fighter Air Regiment) recorded 7 Finnish airplanes to its credit – IG]. Sixty years later on an Arctic summer day, a Russian fisherman caused a sensation in the global warbird-hunting community when he reported peering into the clear shallows of that small lake near Murmansk and seeing the outline of a silt-covered Bell P-39.

Lieutenant Ivan Baranovsky

The museum curators know that Baranovsky was flying the airplane because when salvagers pulled the P-39 from the lake, they found his remains inside. They also found the airplane’s maintenance log, tracing the journey of P-39Q no. 44-2911 from Buffalo along a string of northern U.S. air bases to Alaska, where it was handed over to a Soviet pilot. It was one of 2,565 P-39 Airacobras that followed that route to World War II’s Eastern Front—and the only one that made it back.

Bell P-39s were but a small part of the war materiel sent abroad during World War II. Even before the United States became a combatant, the January 1941 Lend-Lease Act authorized a multi-billion-dollar effort to arm and feed countries already fighting. By war’s end, the Lend-Lease program had exported goods ranging from bombers and locomotives to Spam and paper clips. Under the terms of the act, weapons and industrial equipment were expected to be returned or paid for, once hostilities ceased, unless they were destroyed in combat. In that case, they were written off. The Act led the United States out of isolation and prepared it for war; it also made possible a singular, cautious instance of cooperation with the Soviet Union, an unknowable ally trustworthy enough for fighters but not for strategic bombers.

The P-39 pulled from northern Russia’s Lake Mart-Yavr in 2004 is a symbol of what this cooperation meant to both sides. A U.S. fighter aircraft, originally unloved, found its best use in the Soviet Union, the nation that sacrificed more than any other to defeat the common enemy. And the Soviet demand for arms helped build U.S. manufacturing might.

“The aircraft industries of western New York built 30,000 aircraft during World War II,” says Hugh Neeson. “That’s 10 percent of the country’s wartime production.” Neeson, 77, a retired vice president and general manager of Bell Helicopter Textron [should be Bell Aerospace – IG], is the development director of the Niagara Aerospace Museum. In early 1940, almost two years before America entered the war, Bell Aircraft was “a struggling young company,” says Neeson. That year an order from France for 200 P-39s, accompanied by a check for $2 million, pulled the company from the brink of bankruptcy. (France surrendered before the country could take delivery.) The 20 P-39s delivered to the U.S. Army beginning in January 1941 were the first of an eventual 9,584 produced—half of them for the Soviet Union through Lend-Lease.

As orders for fighters increased, so did the Bell workforce, expanding from approximately 2,000 in 1939 to more than 32,000 in 1943 at a brand-new factory in the Wheatfield suburb of Buffalo. When Sandra Hierl grew up in post-war Buffalo, the aircraft factory was still a landmark in the town. Her mother, Eleanor Barbaritano, and her grandmother, Teresa Barbaritano, had worked there, part of a now-famous wartime demographic, exemplified by Rosie the Riveter: women who filled the jobs vacated by men who went to war. “My mother was very handy with things like a soldering iron,” says Hierl. “And I’d ask, ‘How do you know how to do that?’ and she’d say, ‘It’s what I did during the war.’ They were very proud of what they did. My mother was 19 when she worked at the factory, long before she had me. She told me about taking the bus to work—she and my grandmother. I think it was a lot of fun for her.” Hierl’s mother died in 1979, at 55.

Shortly after the P-39 arrived at the Niagara museum, Hugh Neeson got a call from the son-in-law of a former plant worker who told him to look closely at panels inside the fuselage when they were taking that aircraft apart. “The girls used to write their names and addresses on them,” he said. Sure enough, the museum conservators found two names: Helen Rose and Eleanor Barbaritano.

“My mom had told me about that,” says Hierl, laughing. “It was probably something a bunch of teenage girls thought was hilarious. Now and then a pilot would write to one of the women and thank them for the good work they’d done.”

Hierl, who lives in Connecticut, returned to Buffalo last April to see the airplane her mom had helped build. “She had signed her name and address in pencil on this metal plate, maybe five by eight inches, that goes into this little opening. When I looked in to see it, I put my hands on both sides of that opening and thought, “My mom would have done this.”

ON CHRISTMAS DAY 1943, the maintenance log shows, no. 44-2911 left the factory on the first leg of its journey to the Soviet Union. The Lend-Lease flight path skirted the southern shore of the Great Lakes before turning northwest to head for the high plains along the Canadian border. Members of the WASP—Women Air Force Service Pilots—ferried the aircraft on the first legs of the journey west. “I flew them quite often from Buffalo to Great Falls, Montana,” said Violet Thurn Cowden last year. “In the wintertime, that route was pretty tricky because by the time you got to Chicago and over to North Dakota, we always had weather.” (Cowden, who learned to fly in the 1930s in Spearfish, South Dakota, died last April.)

Great Falls was the eastern and southern terminus of the aerial highway known as the ALSIB, for Alaska-Siberia. A string of rudimentary airfields on the way from Great Falls to Fairbanks provided maintenance, fuel, and safe havens in emergencies. On the other side of the Bering Strait, a similar chain of airfields stretched across Siberia to central Russia. More than 2,000 P-39s were shipped to the Soviet Union through Iran, but most were flown there on the ALSIB, along with the other Lend-Lease aircraft: P-40 Warhawks, P-63 Kingcobras, A-20 and B-25 bombers, C-47 transports, and AT-6 trainers. All of them paused in Great Falls before starting into the northern wilderness.

“The weather was our biggest hazard,” says Steve Allison, a member of the Great Falls-based 7th Ferry Command, who now lives in Enterprise, Oregon. Allison made 30 trips between Great Falls and Fairbanks. “Once in a while you could make a delivery in two days,” he says, but “in wintertime, [it could be] 10 days before you got back.” Because of the horrific weather, ferry pilots routinely took more than a week covering the 1,200 miles of the U.S. side of the ALSIB. Allison recalls that during a routine stop in the Yukon Territory town of Whitehorse, the temperature hit –54 degrees Fahrenheit. When temperatures got that low, “the oil was so thick it was on the order of molasses,” unless dedicated heaters were used to keep the engines warm. At the time, weather forecasts in that area of the world were unreliable, and flying the route, says Allison, was a matter “of making your way through mountains and dodging snowstorms.”

Few of the pilots were trained for instrument flying, and for many, the most important navigation aid was the new AlCan highway, a road cut into the wilderness to link the airfields leading to Alaska. Still, it was easy to get lost flying in the vast Yukon; 80 U.S. airmen died ferrying aircraft along the ALSIB. (On the other side of the Bering Strait, the death toll among Soviet airmen reached at least 109.) In his 1998 book Warplanes to Alaska, historian Blake Smith recounts the searches for ferry pilots who became disoriented as they attempted to cross the snowy wastes. Sometimes the rescuers found the pilots in time; as often, the remains were discovered long after the disappearance, if at all. Lieutenant Walter T. Kent’s last flight was typical of many. On October 27, 1943, Kent flew his Cobra into a snow storm in the mountains of the Yukon, became disoriented in the clouds, and flew into the ground. The wreckage was discovered by a Royal Canadian Air Force helicopter searching for a civilian aircraft—in 1965. Kent’s P-39 was identified by its data plate, and searchers recovered a high school ring inscribed with his name.

The maps pilots used for the ferry flights, says Smith, “were mostly stuff that had been copied from the bush pilots, and notable landmarks could have been way off [from the actual location]. It was like being a bush pilot in a fighter plane except the speeds are much quicker, and they had to make decisions a little quicker.” So empty was the landscape that the airfields constructed along the way “were really like an aircraft carrier in the middle of the ocean,” says Smith.

“What they faced in the first year and a half was a lot different than how things were at the end of the war,” Smith continues. “It was the coldest winter in over half a century. They were ill prepared for everything.”

In this early period, ground crews were working outdoors and sleeping in tents even in subzero weather. “Those poor boys,” says Allison, “they worked out there, under all kinds of conditions, and they did a tremendous job.”

ALL WARBIRD ENTHUSIASTS have a favorite fighter from World War II. British fans swoon over Spitfires; for Americans, it’s often the P-51 Mustang or the P-38 Lightning. But for Ilya Grinberg, it’s the P-39. An electrical engineering professor at Buffalo State College, who was born in Ukraine and earned his doctorate in Moscow, Grinberg is also an expert on Soviet aviation history and the creator of lend-lease.airforce.ru, a Web site in Russian and English stocked with historical documents, interviews, and commentary on the aircraft that the United States sent to the Soviet Union during the war.

“I do love the P-39,” says Grinberg. When I visited his campus office, where technical volumes on power distribution fill his bookshelves, I noticed the screen saver on his computer scrolls through a parade of aircraft from the earliest Soviet fighters to modern Sukhoi jets. “I consider it one of the prettiest airplanes of the period with a number of innovations that are the signature of modern airplanes: tricycle gear, teardrop canopy, radio button on the throttle—the pilot doesn’t have to take his hand off the throttle to key the mic.”

Few U.S. Army Air Forces pilots—and fewer Royal Air Force ones—would have had such nice things to say about the P-39. In 1940, the British purchasing commission ordered 675; the RAF, after four missions, gave most of them back—except for 200 they charitably shipped off to the Soviet Union. Had the aircraft been equipped with a turbo-supercharger, which had been the plan, the British pilots might have been happier. But superchargers were an emerging, unreliable technology that caused constant problems, and Larry Bell, president of Bell Aircraft, had succeeded in convincing the U.S. Army that the supercharger should be removed from the airplane’s engine. Without a supercharger, though, the fighter was useless at the high altitudes where British fighter pilots had to fly to protect their strategic bombers from Luftwaffe fighters.

It may come as a surprise to the admirers of Mustangs and Lightnings that the highest-scoring U.S.-made fighters in World War II were P-39 Airacobras, flown by Soviet pilots. Throughout the war, combat on the Eastern Front rarely occurred above 20,000 feet. Against the Red Army, German aircraft flew ground attack and close-support missions, down at low altitudes where the Cobras could strike. Eight Soviet P-39 pilots shot down at least 30 German aircraft each, and the highest-scoring Soviet ace, G.A. Rechkalov, scored 48 of his 54 confirmed kills in a P-39. [Rechkalov has 61+4 confirmed victories of which 54 were scored in P-39 – IG]. The Soviets called it Kobrushka—Little Cobra.

In 2004, salvagers pulled a Bell P-39 from a Siberian lake, where 60 years earlier pilot Ivan Baranovsky had crash-landed it

At the time it entered operations, the airplane was the only U.S. fighter with the engine located behind the cockpit. Bell chief designer Robert Woods wanted the nose section free to carry a 37-mm cannon, which fired through the propeller hub. “Normally, one strike on an enemy fighter and he was finished,” said World War II ace Nikolay Golodnikov in a 2003 interview published on Grinberg’s Lend-Lease Web site. The cannon fired a round that “no engine could withstand,” explained Golodnikov.

There are military aviation histories and Web sites in which you can read that Russians used the P-39s as tank busters, flying ground attack and strafing missions. “That’s a fairy tale,” says Grinberg. “It flew air superiority missions. Yaks and Ilyushin Sturmoviks flew in the ground attack role, at low altitude. The P-39 plugged a very important gap” by prowling the mid-altitudes used by the German and Russian bombers, Grinberg says. [Should be “by prowling mid-altitudes from which Germans attacked Russian bombers and Shturmoviks” – IG].

“If we had flown it [as] the Americans outlined in the aircraft’s specifications, they would have shot us down immediately,” said Golodnikov, a retired major general in the Soviet air force. “This fighter was a dud in its [design] regimes. But we conducted normal combat in ‘our’ regimes.”

Cobras had another feature the Soviets desperately needed: good radios. Before World War II, only one in 10 aircraft was equipped with a radio, and “they were poor excuses for radios,” said Golodnikov. “Garbage! The circuitry was wound on some kind of cardboard material. As soon as this cardboard got the slightest bit damp, the tuning of the circuit changed and the whole apparatus quit working. All we heard was crackling.” To communicate with their pilots, commanders relied on hand signals. With the arrival of the P-39 and other Lend-Lease aircraft, Soviet pilots were finally able to communicate effectively, and this ability was a significant factor in their success against the Germans from 1943 on.

NO. 44-2911 REACHED FAIRBANKS on January 9, 1944, and was accepted by a contingent of the Soviet air force’s foreign service. Nearly a month later, on February 1, a Soviet pilot flew the airplane west to Nome and across the Bering Strait to the Soviet Union. The P-39s were flown in groups of six or more, escorted by a North American B-25 or other medium bomber with more sophisticated avionics than those in the P-39. Hopping from base to base across Siberia, in March the aircraft reached a central Siberian base at Krasnoyarsk, the end of the ALSIB. There it received the designation White 23 and may also have been repainted with Soviet markings, including the red stars it would wear.

White 23’s log shows that it flew several missions from a base near Murmansk during an October 1944 offensive to drive German forces from the Finnish town of Petsamo. Ground forces were pushing the Germans back; they occupied Petsamo and a Norwegian port city, Kirkenes. On November 19, Lieutenant Ivan Baranovsky was to fly the airplane with his squadron to the recently captured air base Luostari, near the Norwegian border. White 23 took off from the base near Murmansk, but did not make it to Luostari.

In 2010, workers at the Niagara museum lifted the engine from White 23 and found two gaping holes in the engine block. “The engine had thrown two rods,” Hugh Neeson says. Grinberg believes the poor quality of lubricants explains the crippled engine and Baranovsky’s attempt to land on Lake Mart-Yavr. Neeson asked Grinberg to track down the pilot’s family to let them know. Working with a Russian group that investigates the cases of soldiers and airmen missing in action, Grinberg quickly found telephone numbers for Baranovsky’s brother and nephew. [My gratitudes to Ilya Prokofyev – IG].

GRINBERG STARTED his Web site on the Lend-Lease program, he says, as a way to remember and honor the past. “The people who fought, these people who flew and serviced these airplanes, there are very few of them still alive,” he says. “With every month, literally, there are less and less of them. I think the world should know who they were and the weapons that they fought with and what they felt. How do they feel, really, without any limitations of what they could say or could not?”

The Soviet recovery from the initial German onslaught in World War II is miraculous. Operation Barbarossa, the surprise Nazi attack in June 1941, decimated the Soviet air force. Within the first week, the Luftwaffe destroyed approximately 2,000 Russian airplanes, most of them as they sat on the ground, while losing fewer than 40 of their own. From this devastation, the Soviets rebuilt while they fought. They moved their factories east, away from attacking German aircraft, and eventually produced more than 140,000 aircraft, among them almost 60,000 fighters.

Post-war Soviet propaganda claims Lend-Lease aircraft did not play a significant role in the Soviet defeat of Germany because they represented only 13 percent of the aircraft the Soviets fielded. “And this figure continues to sit in the public consciousness,” says Grinberg. But to have supplied the 9,775 fighters sent by the United States (which included Curtiss P-40 Hawks and Bell P-63 Kingcobras), the Soviet government would have had to build four more factories, according to Grinberg, a project that would have drained resources and taken much longer to accomplish than merely taking deliveries from the United States. The resources that would have been required to build factories were instead sent to the front to repel German attacks. The Lend-Lease aircraft did not change the outcome of the war, he says, but without them, defeating Germany “would have cost many more millions of lives in several more years of fighting.”

Grinberg and his Web site also played a role in the Niagara museum’s acquisition of White 23. After the aircraft was recovered, it was moved to England by Jim Pearce of Warbird Finders, an aircraft recovery firm specializing in World War II aircraft. Grinberg posted an article about the recovery on his Web site that quickly drew attention across the world. [http://lend-lease.airforce.ru/english/articles/sheppard/p39/index.htm].

He also called Hugh Neeson. “Wouldn’t it be wonderful if you could get the airplane?” Grinberg said. With introductions from Grinberg, Neeson visited White 23 at its British home. “As soon as we saw [it],” says Neeson, “we said ‘That’s gotta come back to Buffalo.’ That was 2008.” Neeson used the museum’s assets and found additional sponsors to buy the aircraft for $400,000.

On August 27, 2006, the Alaska-Siberia Research Center dedicated a monument in Fairbanks to the U.S.-Soviet partnership formed during the Lend-Lease program. At the dedication, before an audience including war veterans from both sides, Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld, Senator Ted Stevens of Alaska, Russian Ambassador Yuri Ushakov, and Russian Minister of Defense Sergei Ivanov, the research center awarded Ilya Grinberg a medal for educating people about Lend-Lease. Grinberg says it was “the most symbolic moment of my life.” He told the audience, “I grew up in Ukraine and I knew many friends whose parents were flying P-39s. And now I live in Buffalo, where I know many people whose parents worked at Bell and built P-39s. And here in Fairbanks, these planes changed hands.”

White 23, renamed by the museum Miss Lend Lease, will make its first public appearance at the Thunder Over Niagara Air Show, on the weekend of September 10 and 11 at the Niagara Falls Air Reserve Station. It is not being restored, but rather conserved in its present condition for display at the museum’s exhibit space in the former terminal of the Niagara Falls Airport. Exhibit designers will make simulated snow and ice as the airplane’s support. “Our intent is to show how it landed on the ice at the end of its flying trail,” says Neeson. The exhibit will include the maintenance log and another discovery that salvagers made when they pulled the airplane from the lake: 11 small cans of food that had been stashed in ammunition bays. They were labeled “made in USA.” [These cans were not delivered to the museum – IG].

Frequent contributor Tim Wright, a photographer in Virginia, has found that he can sometimes create a better picture with words than with a camera.

Air & Space Magazine, September 01, 2011