– Please, introduce yourself.

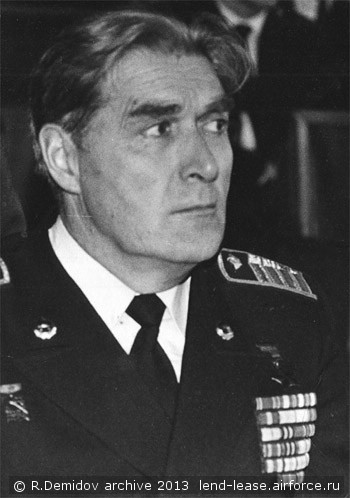

I am Rostislav Sergeevich Demidov. I was born in Kharkov on 4 November, 1922. I turned 90 this year. I assembled all those who could come, mostly my cadets, who did not participate in the Great Patriotic War. Almost all of them had become generals. Among them was Colonel-General Deineka. He is my full “god son.” I went to the city Nikolayev, which I commonly visited after the war, and noticed a talented young pilot there. 24 years old, fine pilot with exceptionally well working head. With a lot of difficulties, I persuaded the VVS Commander and the Chief of the Academy (Kuznetsov Naval Academy in Leningrad – ed.) to accept him to the academy. At that time the screening was very rigid for age and position. Only squadron commanders and higher could be accepted, while he was just a regular pilot at the time. He was still accepted, and I was not mistaken. He was a very talented and smart man! [Colonel-General V. G. Deineka was the Commander in Chief of Naval Aviation of the Russian Federation from 1994–2000 – ed.]

Rostislav Sergeevich Demidov, 1945

– Who were your parents?

Dad worked as a chief engineer at the “Red October” plant in Kharkov before war, and then he fell victim to the purges. Mom was a dentist; she graduated from Berlin University before the Revolution. She came from a rich family. I was the only child in the family and was born late; Mom was 40 years old by then.

– Why your father was sent to prison?

He was not imprisoned, he did not do time. He was punished for being an engineer-senior lieutenant in White Army. That was enough in those days. He was issued a “white card,” a so-called “wolf ticket,” so he couldn’t work and earn money. He was stripped of all rights. He was not allowed to work or participate in elections. He could do nothing, so he worked in his private garden and yard. During my last two years in school, grades, I had to work as a draftsman. Old friends of my dad from the plant gave me work, so that I could earn something along with studying.

– What was your relatives’ attitude toward the Soviet State?

Excellent. Mom worked all the time and was also a member of а village council. Dad returned to the plant, but not as a chief engineer, rather an ordinary engineer.

– When did you choose to tie your life to aviation and the Army?

You know, it was in 1940, when we were about to graduate from 10th grade. It was absolutely clear that there would be war. We also understood that going to war as a private meant sure death. We needed to graduate from military school. So we decided… At first I wanted to go to naval school, and then switched to flying.

– You studied at Nikolayev School named after Levanevskii? How did you apply for it?

Oh… The path was long. In 1940 I finished school with a gold medal. I went to Leningrad and was accepted without exams to Dzerzhinsky [Navy – ed] School. But there I was sent to clean toilets, which my pride couldn’t allow, so I quit.

Rostislav Demidov as a flight school cadet

– But didn’t all cadets have to do this in their turn?

Yes, it was common work. But I did not like it. So I went to Levanevskii School, where the toilets were cleaned by people hired for that task. We had only to study.

– How did you make it to the flight school? How did you pass exams and mandatory [medical] commission?

I had left Leningrad Naval School named after Dzerzhinsky with a medical diagnosis that I had a punctured eardrum. When I passed the medical commission at the flight school, none was found. To be honest, I had faked it. I wanted to leave naval school; I didn’t like situation there. I took my documents and left for Nikolayev straight away. There were no problems with acceptance, since I had a gold medal. I was accepted without exams and studied with pleasure.

– Do you remember how many regiments there were in the school?

There were two regiments. One was equipped with the MBR-2, the other with the R-5.

– How many airplanes were in these regiments?

I can’t recall. I believe about 30 in each, but I may be wrong. I was assigned to the MBR-2 regiment.

– How would you describe this airplane?

It was an awful aircraft, a constant source of trouble. It was built out of thin plywood. It had a 108 lb. anchor, so that it would not drift when sanding at sea. After touchdown the navigator, that’s me, had to get out of the cockpit and drop this anchor into the water. When it was released, it tended to fall to the fuselage side instead of the water. Water could get into the fuselage and the airplane would sink very rapidly. Of course, we tried to avoid this problem [laughs – ed.]

When we were taking off, the most dangerous things were “deadheads” – water-soaked logs in the vertical position. If we hit one, it would be all over. At take off a huge amount of water poured at navigator, who had to stand in the open cockpit, looking out for those logs. The water was cold, but we still did not catch flu, even though we got up to altitude in wet clothes.

– That’s when you were cadets?

Yes, when we were cadets. When we graduated, 20 men were sent to the Far East, where we were sent to different units. I was sent to the mine–torpedo regiment.

– When did you graduate?

It’s difficult to say, I had forgotten… The war went on for a long time.

– How did you find out that war had broken out?

When the war began, we were still studying; everything was terrible, chaos, confusion. We were issued weapons and sent after German spies in Nikolayev. We walked on patrols.

– Were squadrons or regiments formed on the basis of your school? Were cadets included along with instructors?

There were such squadrons, but I didn’t see this. We were sent to the rear before that. Mostly they were equipped with instructors, but some cadets were present. I knew one guy, Valentin… I can’t say, if he is alive or has died already… He flew to Stalingrad. A squadron formed from our school and equipped with the MBR-2 bombed the Germans in Stalingrad.

– Where you were sent to from Nikolayev?

1Some of us flew with the airplanes and others were sent by barges. Along with my comrades, I arrived in Stalingrad, where we were loaded on barges and sent to Astrakhan. I remember that well. The barges were loaded with bags of sugar and barrels of herring. For almost a month we traveled from Stalingrad to Astrakhan. We were not fed, there was no bread at all, and so we ate salted herring and drank tea with sugar.

– Those who were training on the MBR-2 were sent to Astrakhan, but where were those who were training on the R-5 sent?

I don’t remember. I can say for sure that there were 200 men on board our barge.

– Did you make training flights in Astrakhan? Were there any airplanes?

We were not in Astrakhan very long, a couple of weeks, maybe. We had no airplanes and thus we did not fly. We slept in fishing nets and ate fish. It was somewhat of a transit center. Then we received documents about graduating from school, and we were sent to the Far East by freight train. We traveled for two month to get there. I truly trained in the regiment there.

– Was there some kind of graduation ceremony?

There was no time or need for that; we simply were issued documents.

– As far as I know, Nikolayev aviation flight school was evacuated first to Mozdok and then to Bezenchuk.

Yes, I begin to recall… I was in Bezenchuk, but for a very brief period of time. Then – Stalingrad and Astrakhan.

– Were you bombed or did you see Germans before evacuation?

No. We were evacuated before the Germans reached Nikolayev. We were sent out to conduct anti-parachutist patrols at the airfields and mock-up air bases, but there were no actual engagements with Germans.

– Could you tell us about these mock-up airfields? Were they air bases of the Levanevskii School?

From Nikolayev we were sent to Yeisk. There we were supposed to train. It was a school named after Stalin that trained fighter pilots. We had to guard mock-up bases. There, in Yeisk, were sandy islands on which false airfields had been constructed. Broken, written-off airplanes were dragged there, and machine gun nests were placed around it. Old turrets with machine guns were removed from damaged and destroyed airplanes. So we patrolled there. The Germans attacked them, while we shot at the Germans. Of course we did not shoot down anyone, but we fired.

– Were you set up on Yeisk Spit?

Yes, right there in Yeisk, on the spit, our entire operation. Around us were airfields and islands.

– Were you transferred from Nikolayev to Yeisk with airplanes?

We flew with a small portion of the planes.

– What did you know about the prewar conflicts — Spain, Khalkhin-Gol, Finland?

Only general information…

– You had MBR-2 and R-5 airplanes in your school. Were you given any information about other types of airplanes?

No, only these two types. When we arrived in the Far East, we began studying the DB-3, which we later had to fly.

– There was a navigator, Gregory Avanesov, in St. Petersburg, who used to fly the MBR-2. Did you know him?

Gregory! Of course I knew him; he used to be my best friend. He was an anti-submarine warfare navigator with the MBR-2 squadron.

– He told us about a special aiming technique, used with MBR-2 – by machine gun sight. Did you use this method?

No, I never used machine gun as bombsight. We did not use it that way.

– Was training cut back after the war began?

Yes, it was shortened. We were not fully trained, and that’s why we were sent to the Far East. There we got a year of good practice.

– You were sent to DB-3F there?

No, we began flying the DB-3B, that’s with the short nose. We were divided among crews as “understudies” of the navigator. This airplane had a drastic flaw. We flew at high altitudes there, and it had two machine guns in the nose with large holes [in the plexiglass]. Wind blew right into the navigators’ compartment. At an altitude of 9,000 meters, the temperature could be lower than -57 degrees centigrade. It was cold. We had a mole skin mask, three pairs of gloves, and still got frostbite. It was a major flaw. This problem was solved in the DB-3F.

– You ended up in 4th MTAP {mine-torpedo air regiment – ed}? HSU Minakov also began in that regiment. He recalled that it was a good regiment with a good school.

Yes, I made it to 4th MTAP. The Regiment was truly excellent; my main knowledge was received not in school, but in this regiment. We were well trained, and that is why we made it through the war.

Later, many years many, when I was a teacher myself [in the Academies – ed.], I always said that it is important not to only get information, but to be able to think it through. Your move should be thought through, a prognosis should be made and the best possible course of action be executed. That is what I taught my cadets about, and many of them became generals. Some 36 candidates of science were prepared in the faculty at VMA over a 10-year period. I did not select adjunct students — “crammers” — as being the outstanding ones. I believed they were a lost cause — one could not make a scientist from them. A “crammer” can remember other peoples’ achievements and knowledge, but he cannot create his own, new. They are not trained to think.

– Are you tired?

Yes, I am. I would like to have a cup of tea. Don’t be fooled by my active state; I’m over 90 already [laughs – ed.].

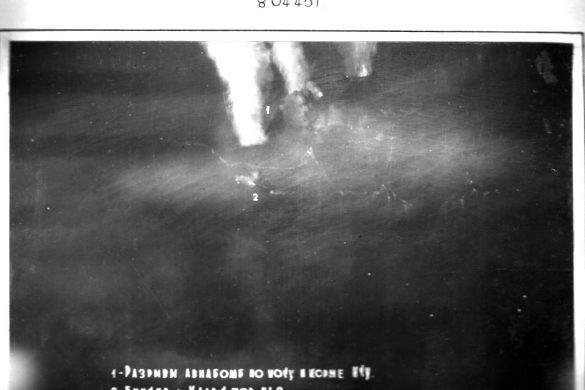

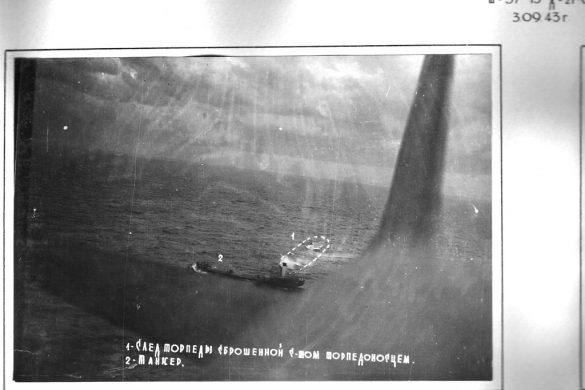

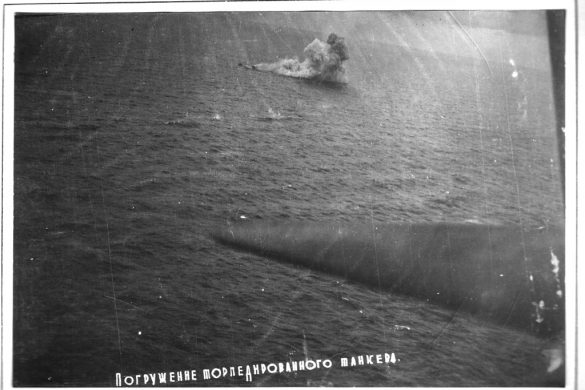

– Take a break. We, meanwhile, will look through the photos… They are of surprisingly fine quality, even though they were made by film cameras.

Yes, it was films. Some photos I made 60 years ago, but now I have digitized all images and printed them… [laughs – ed.]. There are a lot of photos of my wife.

I was very lucky to be married to her. We lived together for 63 year, we were very friendly, and not even once did we have an argument. I took a lot of photos of her. We had an excellent family… Here is her last photo, which I made in 2010… She wouldn’t listen to me, and died from the complications of hernia. When I brought her to the hospital, it was too late.

My wife worked all her life, in Leningrad Pioneer Palace. She headed up the children’s art section. I still can see her, when I close my eyes. She delivered me a son, a great boy, but doctors forbade us to have other children, because she almost died in process.

– Very beautiful photo. Was she a painter?

She was an artist all her life long, all the paintings in my apartment are made by her or by my son. I do not keep any other painters work.

– All HSU’s were sent to the artists, so that they would make their official picture. Do you have such portrait?

I chose not to go. I have a portrait made by my wife. It was exhibited here, and even abroad. She drew it in 1957.

Here are photos from the war period. We made them our selves. I had a Leica during war.

– It was forbidden to make photos during war time. Were you informed about it?

We spat at these orders, and made photos. Our Special Department officers were pretty smart, and we did what we wished. Unluckily, very few photos survived, but it is our fault… Here is a Boston [A-20, also known as the Havoc, of which the Soviet Union received 2,900 in the Lend-Lease program – ed.], but not mine; it will be in another picture.

– By the way, it is a rebuilt airplane.

Modified. All the Bostons were rebuilt in Leningrad, at our aviation plant for navigator accommodation. We couldn’t fly without navigators.

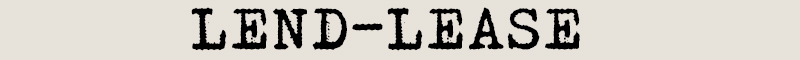

…This is a photo of my airplane, “Number 6,” in flight, taken from another aircraft by my friend . It was shot down by our own AAA. They were based at our Panevezhis airfield. We had taken off for a mining mission.

– How did they manage to make such a mistake?

Panevezhis was severely bombed by the Germans then, and on that particular night they did it again. The skies were pierced by searchlights. There was panic and complete chaos on the ground. We came in right in the midst of it all. We were on final approach and fired off a flare to mark our identity. But the AAA gunners decided that it was fascist plane on a bombing run and opened fire. Our engine was hit. The pilot said to me:

-Bail out!

– I won’t. They will kill me in the air, thinking that I’m German, – I shouted in reply. -Land!

Eventually we safely landed; we had some bruises and scratches, but we were alive. The airplane was a complete wreck, though.

Here is Vyacheslav Balashov [Hero of the Soviet Union – ed.] with his wife. We were very friendly. We became friends when I came to Leningrad to work at the Academy. We lived in a dacha during summer time, where we were a part of great, cheerful and smart company. My distant relative Rudolf Ferdinandovich Its, academic – ethnographer, a traveler with a great mind, was always the toastmaster. I thought: I have a myriad of tales, too; I worked a lot as a lecturer and had a good tongue, why can’t I be a toastmaster? From that time until this, at all the holidays, I am the toastmaster. Not so long ago, I was the toastmaster for a friend’s 60th birthday. There were 50–60 people; it was difficult. There were children, people of my own age, and some who were younger — of various ages. I had to entertain all of them, and I accomplished this task. I came home from there hungry as a wolf because I spent so much time telling stories or proposing toasts, that I didn’t even eat [laughs – ed.].

– Were you eager to get to the war, when you were in the Far East, or were you trying to learn as much as you could?

It was absolutely clear to me that I had to study.

When we arrived in the Far East, we came to “Heaven.” We had an officers’ club, movies on a daily basis, concerts, dances on Saturdays and Sundays. Even though we were mostly young and single, we lived in apartment buildings specially built for officers. So, it was true Heaven. Some time had passed, and they tore down the officers club. We were told:

“People are fighting a war and dying out there, while you are watching movies here and dancing.”

It was the first sign. The second one was when we were thrown out of the officer apartments:

“People are living in dugouts at the front, while you are here showing off.”

So we had to make dugouts for ourselves and live there. It was simply stupid. It went this way until our superiors were changed. New commanding officers came from the front line.

– Who initiated these changes, military or political officers?

Political officers. We did not like them. During my entire life I saw perhaps two good ones.

– Political officers were divided into two categories: “Do as I do” and “Do as I say to do.” In the Baltic Fleet VVS was a famous and universally liked political officer, Serbin. He flew combat missions and actively participated in combat.

I knew him well. He was a true political officer and excellent pilot. We had another good one – Kalashnikov. He was removed later, because he was good man. All the other political officers whom I met during wartime were crooks.

I remember how at the end of war we were called to the command post. We constantly had to fly special missions, because we were experienced pilots. The regiment commander issued an order:

“I have a special mission for your crew. Fly to Germany, land at Kohlberg Airfield, which was occupied by our troops yesterday. You will take a political officer – a representative of the commander-in-chief’s staff.”

He said that we were to be escorted by 12 fighters. We were shocked – during the entire war period we never had such escort, no more than a couple or two. This time – a full squadron.

So, we made it there, this representative said:

“You are to sit here with no right to leave.” Then he left the airfield. When he returned, he brought antiques, paintings, radiolas, crystal…

Supply officers had set up warehouses at the airfield. All sorts of goods were brought there.

– Were they emptying abandoned houses?

Everything came from the empty houses; the population had fled from us. There were special trophy teams that gathered all this stuff. The political officer loaded our airplane to the top. We haven’t taken anything. I brought only a single small ring from Germany as a memorabilia.

When we were based at one airfield, we had to live far away from our airplanes, and had to walk for almost five kilometers one way. We said to our gunner Vaniamin:

“Go to the warehouse and get a light motorcycle that we can ride to the airfield.”

He went there, but returned empty handed. We went there ourselves, and said to supply officer:

“Issue us a motorcycle; you have half a hundred there with no use for them.”

“Well, you know…”

He refused. Later we found a good German motorcycle, a “Victoria”, and rode it for two years. There was a radioman, the chief of radio operations of the regiment, who was of thin complexion and looked like a gnome with a large nose. He begged this motorcycle from us and went right through the shop window in Pyarnu. He suffered some injuries, but our motorcycle was totally wrecked. The radioman healed, but our motorcycle had perished.

– Were you assigned to the 1st Guards MTAP when you arrived from the Far East?

No, not to the 1st Regiment. We, two crews, were assigned to the newly formed 51st MTAP. When we arrived, there were no commanding officers, neither regiment commander nor squadron commanders. We came to the posts of flight commanders. We saw “Bostons,” which were flown to the Baltic from the Northern Fleet for the first time. We were told:

“You may fly them.

There were no instructors, and there was not a single man familiar with these airplanes. The non-flying leadership pressed us:

“You are pilots, so get inside and fly them.”

We searched for instructions, but when we finally found them, they were all in English! But most of us had studied German, as we were planning to fight against them.

– Was it in 1943?

Yes, 1943.

– I thought that you underwent training first, and only then were sent to a first line unit.

No, we were transferred to Bostons straight away. I can’t recall which month it was, spring time, I believe. It was at Novaya Ladoga airfield, where we were stationed for a long time. We searched for somebody who knew English. We brought a young female teacher from the local school. She glanced at the text, but if she knew general English, she knew no technical terms, and thus was of no help to us. We got into the cockpits and began examining them ourselves; airplanes are all alike all round the world. The most difficult part was that all the instruments were marked in miles and feet, while we were trained in the metric system. It was not common to us and caused some discomfort. We had to recalculate everything. It was quite awkward, but there was no other way. Later, much later, all the instruments were changed in our planes.

– Were the instruments changed? Which ones were used instead, Soviet ones or localized American?

We were given Soviet instruments. We were told that they were identical.

– Did technicians help you to master the airplane? They should have studied it to the last bolt.

We studied ourselves, but the ground crews helped a lot. First, we simply sat in the cockpits and learned the instrument panel; then for a couple of days we simply scrambled round the airfield without actually taking off. Then we started flying for real.

– Who was the first to take off?

I can’t recall now. It’s quite possible that it was our crew, since we were the most senior crew in the regiment.

All the Bostons came armed with four machine guns and two cannons in the nose. They were in a gunship version. It had a so called “artillery section” in the nose, but there was no glassing there. But we, torpedo bombers couldn’t fly without navigator. Do you understand? Not every pilot understands.

The pilot is the crew commander. He is a pilot and he should fly the machine, but he should not make tactical decisions. When it is time to plan the approach to the target, and there may be four, eight, or 12 aircraft in the group, you have to command them. The Germans were not willing to swim, so they went all guns blazing at us. If the pilot were commanding the entire group, he would be unable to fully understand the situation; he would be unable to detect threats and he would be brought down. It was quite common. So we talked this over with the pilots. I told mine:

“Aleksandr, you just make sure that we will return home safe!”

That he did; he maneuvered, avoided tracers, fell as a leaf to the altitude of five meters from the water – it was a true circus. That is why we stayed alive. He was not busy with tactical decisions, weapons aiming and use. All this was my responsibility. I was fully free in flight. He piloted, while I commanded the crew as to what they should do. External radio communication was also in my hands. [Pilot A.M. Gagiev was the crew commander in which Demidov flew as navigator – ed.].

Aleksandr Gagiev, Panevėћys

– In the Luftwaffe, the navigator was crew commander.

That is right, but it could never be this way in our aviation.

– Was there taunting between pilots and navigators? I spoke to HSU Yevdokimov, who used to say that: “The pilot is a taxi driver, who brings navigator to the work site.”

We also had such jokes. But I explained how it was in our crew, and that was the only reason why we made it through. The navigator should be like a mother or nanny to his pilot. Those who followed standard instructions to the letter, perished.

– I believe that a smart pilot simply passed some of his duties to other crew members.

Vassilii Minakov was a smart pilot, but there were very few of such ones. Pass my greetings to him, and tell him that I still remember him. We used to live in the same apartment building with him in Leningrad. He is a great man.

– We will! The Boston could carry two torpedoes. Why did you fly with just one?

It was very heavy, unmaneuverable and had a tendency to spin out of control [with two]; that’s why we flew with one torpedo. We used to carry two only when we had to deliver them from Leningrad to Baltic airbases. Combat missions were flown only with one torpedo.

There was a chief of staff in our regiment, a colonel from cavalry, I forgot his surname. He had no idea about aviation. He made us fly with a torpedo and a bomb. He ordered us to drop the torpedo from a range of one kilometer, and then perform a mast-top bombing. That was a complete delirium. We flew out to the coast line and dropped the bomb there. The mission was carried out with only a torpedo.

– Where did you get torpedoes from, and why did you have to fly them from Leningrad by air, and not by trucks or ships? Wasn’t there a problem with aviation fuel?

There was aviation plant in Leningrad, or maybe a warehouse. The Gulf of Finland was still closed for naval navigation due to mine danger, and the roads were long, of bad quality and unsafe.

– How would you describe the effectiveness of torpedo strikes? In percentage.

It’s hard to say; it depended on many factors. I’d say, 30 percent were hits. Mast-top bombing allowed reaching up to 70–90 percent hits.

– Vassilii Minakov fought in the Il-4, and you in a Boston. Could you compare them?

Boston was better because it was lighter than Il-4. The Il-4 was a very heavy aircraft, and it was much less maneuverable than Boston. When we returned from a mission with a success, we would make a low altitude barrel roll with a Boston.

– Barrel roll with a Boston?!

Yes, we did it. HSU [Yurii Emmanuilovich] Bunimovich was killed this way; he caught a dugout roof with a wing tip and crashed. He was performing a barrel roll at low altitude. It was proclaimed to be hooliganism, but it was general practice in the regiment.

– Do you remember how HSU Vadim Yevgrafov died?

Yes, a handsome guy from 1st Guards MTAP. A great man. His death was stupid. I believe that he crashed his airplane into the guardhouse. The regiment commander had punished him for something, I can’t remember what it was exactly. But I do not believe that he could have crashed into the guardhouse by pure accident after that. That couldn’t have been a coincidence. It was a suicide. It was not announced or written anywhere, but it was really that way. [According to the official version, they had sent Yevgrafov in a Po-2 liaison aircraft to Leningrad with a report, and on the eve he learned that he had been awarded the rank Hero of the Soviet Union. Ostensibly, when he was flying back, in celebration, he spun his aircraft . . . He perished accidently. Ed.]

…I had good relations with Borzov. There was a great navigator in his crew, Dmitrii Kotov. But it was common for me to fly with him, too, and we became friends. He was a very stiff man on the ground, and could swear a lot. In the air he was an ideal pilot, obedient and responsive, steady. I was his friend; I witnessed his marriage and knew his wife well. Borzov was an amazing person. [I. I. Borzov, Commander of 1st Guards MTAP; subsequently a marshal of aviation. Ed.]

– Was there a practice to try and “improve” mission results, or you were realistic in your reports?

No, we did not exaggerate. It was impossible to fool Borzov. I remember, how I was once “sentenced” to execution. In the autumn of 1944, I led a group of eight young crews. When they spotted a convoy, they simply turned around and flew home. Only our crew dropped a torpedo, with no success. When we returned to the base, we were told:

“You haven’t accomplished your mission? You will be executed!”

Borzov was absent at the time; it was the chief of division staff. I was being walked to the execution site, when Borzov landed.

“What’s going on here?! What for?”

He saved me then, and chief of staff was removed after this event.

– If you missed, did your commanders severely reprimand you?

Never. Our regiment commander Borzov was a very clever man.

– I spoke to the navigator from 51st MTAP, Yuri Abramov, who flew 10 missions in Bostons before being shot down. He claimed that in his Boston G navigators’ cockpit was set up as a gunner’s compartment, and that he couldn’t see anything except straight down or up.

Yes, that’s how it was. But I flew in a shallow compartment behind the pilot, head-to-head with him. You couldn’t see anything from the rear compartment, while I could see everything from here. The Americans sent all the Bostons to us as gunships, and we were unable to repair them. The front compartment was added in Leningrad a bit later, but we had to fly missions somehow before those modifications were made.

– What did you do under the canopy? There is no place to even turn there!

I helped my pilot, turned my head side to side, increasing his situational awareness. The pilot only flew the plane, I did all the rest. I advised when he should release torpedo or bombs, when to open fire with machine guns. There was also a map in front of me, if it was needed to plot a course.

– Did you fly top-mast bombing missions?

We were the first to be trained in this maneuver. It was in Novaya Ladoga. I had flown a lot of mast-top bombing missions, both at the practice range and in real combat missions. One pilot was lost during practice; a bomb blew up immediately after release due to a faulty detonator.

– You used live ammo in practice runs?

Yes, of course; there was no way to get duds. We used to have concrete bombs before the war. I had flown 30 combat mast-top bombing missions, which is quite a substantial number.

– What kind of targets were used for bombing practice?

We were trained on Lake Ladoga, using normal shield targets. This was a vertical target on floats.

– Did the Germans bother you a lot?

We suffered mostly from Swedish 20mm Oerlikon automatic cannons. For us it was very dangerous weapon, while we were not so seriously bothered by large caliber cannons. We were hit once by one of them, and it was our gun crew that brought us down. I told you this story before.

I can say for naval aviation, most losses were caused by insufficient crew training, and not by enemy actions. We commonly flew mining missions at night time. We flew in three-plane formations – a flight. Some pilots had never flown at night before. When he was caught by a search light and blinded, the pilot immediately lost orientation and simply dropped out of the sky. I can repeat – most losses were caused by lack of training. We always flew very low, near the water, which is very difficult. For example, in a bank you could catch a wave with a wingtip. We had a lot of young pilots, who were never taught how to fly at these altitudes.

– There was a special line at the Shepelev lighthouse which was made to allow pilots to remember how water would look from an altitude of 20 meters.

I cannot remember this, but it is possible. We flew at the altitude of 20 meters above the water. It was very difficult. When a mast-top or torpedo bomber is making its run, it had to pass over the attacked ship. Young pilots often brought pieces of masts from those ships back to the airfield. It was common to untie wires from propellers and to get pieces of masts from bomber fuselages. I did it three times myself from my wingmen’s airplanes.

– Vassilii Minakov tried to make a combat turn to escape after weapons release and avoid passing over the attacked convoy.

It is his point of view. We flew over the target. If you turned above ship and presented the belly of your aircraft, you could be torn to pieces by gunners. We “jumped over” the target and descended as low as possible on the other side again.

– But if one flew over the ship, its gunners had a good, non-maneuvering target as well, and chances to survive were also low.

Some experienced bomber pilots made a run, released their weapon, but instead of jumping over the target they would skid to the side and fly below the deck level, in front or behind the ship. It was a trick for the circus, very complex to perform. To skid an aircraft at such an altitude required ultimate mastery of the plane.

– Losses of flying crews during wartime in the 51st MTAP totaled as 260 men. Can you comment on this?

When we were assigned to the 51st MTAP and were based at Klopitsy, along with 3–4 other regiments, including two regiments from ADD [long-range aviation]. We all flew mining missions to Tallin and Riga bays. Borzov was at the command post. We returned to our base, and nobody could land due to heavy clouds, except us. Borzov called me and Aleksandr:

“How did you manage to land?!”

We had thought through such a situation before and trained prior to becoming operational. There was a road going straight from the Gulf of Finland and we followed it. Clouds never connect to the water; there always is a free space. We would enter it, find the road and follow it to the airfield below tree tops. I got down on the cabin floor and told the pilot:

“Slightly up, slightly down…”

Then we simply dropped out of the sky to the runway from an altitude of 10–12 meters. Borzov was very surprised at that, so he said:

“Would you like to join my regiment?”

We replied:

“Yes, of course!”

In one week’s time, we were transferred to 1st Guards MTAP.

– What was wrong with 51st MTAP?

We liked that regiment, but it was filled with inexperienced pilots. It turned out that we were the most senior in it; everybody learned from us, while we needed teachers ourselves. In 1st Guards MTAP, all pilots were experienced, with serious experience, and were ready to pass it to us.

– 1st Guards MTAP lost 560 crew members during war; 51st lost 260 men. If we are to analyze losses of 1st Guards MTAP, almost half of them fell in the first months of the war, when ground bombing missions had to be flown by small groups without fighter cover. A second rise in losses occurred in the second half of 1944 and in 1945, when the regiment flew anti-convoy strikes and bombed naval bases.

We had severe losses when we went after convoys. In the beginning of the war they had singular ships at sea, and later the Germans began forming convoys, covered by destroyers, corvettes and other military vessels. They had very heavy AAA cover.

– There were heavy losses when you had to bomb naval bases, too, for example, at Libava… Do you remember Stepanyan, he perished there? [Twice Hero of the Soviet Union N.G. Stepanyan – ed.]

We bombed Libava, too. I remember Stepanyan well, I knew him. He was a smart, good, likeable man. There was a time miscalculation in that mission when he was shot down. He and his group of Sturmoviks arrived at the target before the fighter cover joined them. So German fighters shot him down. I had forgotten the details already. I remember that this loss was due to an incorrect arrival time of one of the groups. [There is another version of the event, according to which the first strike group, participating in the operation, arrived earlier than the planned time and attacked the target. Stepanyan was leading the second group, but by the time of the approach of his Shturmoviks, the Germans had readied themselves, and their air defense fighters had taken off to intercept Stepanyan over the sea. Ed.]

– What did you do if crews did not return from combat mission?

…Here is another story. We came from Far East in two crews, I told you about it already. The second crew’s navigator was Gregory Pryakhin, while the pilot was Viktor… I forgot his surname. We lived and flew together all the time. During one of the missions, his aircraft was hit over the target convoy. We escorted him home. One of the engines was destroyed, but he still pressed toward home base. We gave him advice on how to make it better. When we returned to base, we told him:

“Viktor, land immediately.”

“Fine.”

We began landing, when he announced:

“I’m going to make a second attempt.

“No way! Land now! With gear down, or belly land, just do it!” We yelled at him over radio.

“I can’t land!”

He made a second attempt and crashed. They burned to death. Their crew was buried in the nearby forest.

– What had happened? He ran out of fuel? Stalled?

One engine was out, so he lost speed and stalled. He was a good pilot, very good one, but he should have never risked so much, despite his pride or honor. He lost his own life and took another three with him. It happened at the end of the war.

– We spoke about Bunimovich. What kind of man was he?

He was an excellent pilot, from the first generation. They were experienced, and we were fledglings.

– Do you remember other “old school” pilots? Have you met Rakov?

[Twice Hero of the Soviet Union V.I. Rakov, at that time commander of the 12th Guards PBAP (dive bomber regiment). Ed.]

Rakov was very good pilot. I flew with his regiment against Konigsberg. They delivered a punch from high altitude, while we flew lower and we saw his flight. It was magnificent! They flew in 9-ship formation, close to each other.

– I was told that the Pe-2 was a good aircraft, but not so good as a dive bomber.

Yes, it was complex airplane. But I saw over Konigsberg how Rakov’s regiment dove at their targets. It cannot be described by words. Magnificent! What power!

There was an “old” pilot Shamanov, who came from civil aviation. If I’m correct, he flew with navigator Lorin. [Hero of the Soviet Union I.G. Shamanov, then instructor pilot in the Headquarters, Air Forces, Red Banner Baltic Fleet; he flew combat sorties with 1st Guards MTAP. Ed.]

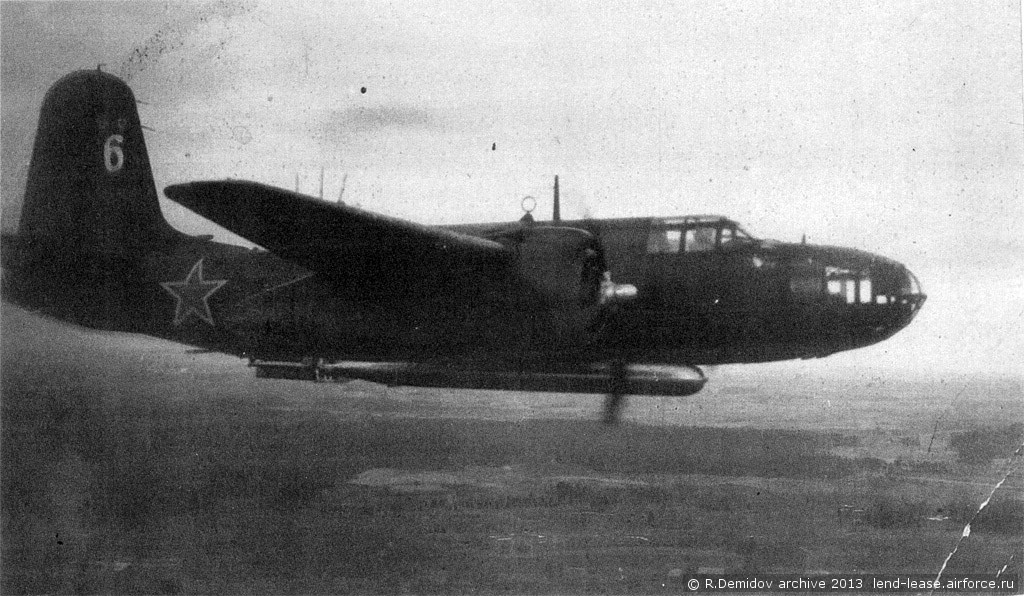

Gagivev is standing on the left side of the photocamera. A-20 on a background belonged to Gagiev/Demidov crew

– Could you describe how crews were formed? Were they fixed, or could they have changed, if needed?

They could be changed, but very rarely. Mostly crews were fixed. My pilot, Aleksandr Gagiev, didn’t fly single mission without me, although I had to fly with another pilots. We were very close to each other, more like a family. The radio operator in our crew was not so great, but our gunner was excellent. I wrote an article, not so long ago, called “Blue 2.” Once, in August 1944, our 12 crews were summoned to strike a convoy. We were young then. Just before takeoff, Ivan Ivanovich [Borzov] said:

“I will not go. You will lead the group in my airplane.”

“Blue 2” was his aircraft. We successfully accomplished our mission, even though we lost one plane. I remember that mission well, and even wrote an article about it. I once started to write a book…

A man from American embassy (it is located on the opposite side of the road) came to me and said:

“You flew American Bostons; please, write a book about it, we will edit it, translate, sell and pay you an honorarium”.

The honorarium was laughable, minuscule. I said to him that I was not interested in his honorarium. So I began writing a book, including an introduction. I gave him the text for corrections, he edited it and returned it to me. On the title page, I was not even mentioned among the authors! So I said straight out that I was not interested anymore and sent him away. I dropped the idea, since I had other things to do.

In that mission, when we flew in Borzov’s “Blue 2.” Our gunner, Sokolov, shot down an enemy Messerschmitt 109. All 12 crews witnessed and confirmed it. He was issued an Order of Lenin for that.

– Which planes did you fly during the war period?

I flew Bostons, a little bit of the DB-3f with the pointed nose, and the MBR-2 when I studied at the school.

– Here is a photo, where your crew is standing near an airplane. It is marked with two ships and a U-boat symbol. It is your work?

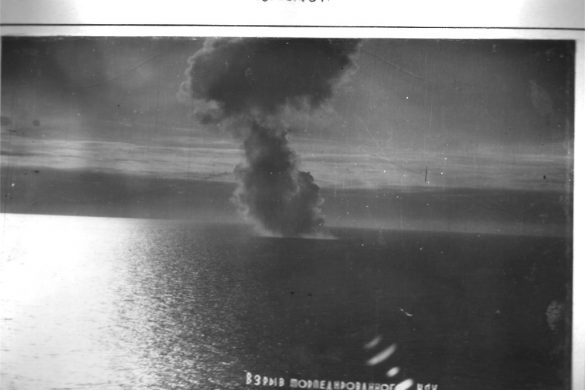

It was absolutely spontaneous. We were to attack a U-boat base in the Klaipeda–Memel area. There was one large merchant vessel, our main target. We were to attack it from a different direction, and when we were going our way, a U-boat emerged from the water right in front of us. We torpedoed it. It was pure luck that I pressed the trigger.

– Navigator Abramov said . . .

There were a lot of good young men. There was a young navigator Rashevskii. Ram Zaifman… He searched for me in Moscow after the war, but somehow we did not meet. There was another young navigator in Mikhail Tokarev’s crew. I remember, we had to attack ships in Memel. Naval AA was assisted by heavy AA from the shore. Shells as tall as men flew at us. But they were not shooting at us, but at the water. A column of water rose after the explosion. Their crew hit such column and vanished. They flew 30–40 meters to the side from us; it all happened before my eyes… It was like hitting a concrete wall.

– Minakov and Abramov told me that they didn’t use torpedo sights during attacks, while Razgonin said that his navigator used one, while he followed navigator’s orders. According to recent research, Razgonin was credited with the highest real tonnage sunk. Did you use a torpedo sight?

Sometimes, but mostly not. Most important was to get within 900–800 meters from the ship and aim at the center of the ship. We did it by plain eye, and there was no way for the ship to evade.

– But there was no sense in releasing the torpedo at the range less than 600 meters, or it would not be armed.

Yes, but if you will drop it from 1000–600 meters away, it will surely hit the target.

We were friends with Razgonin. You know his story, how he was shot down, how he was captured and then escaped… There is no sense in repeating all this. He was my friend, so I called him to live at my apartment. We lived well together. Then he was summoned for a check, and sent to jail. Then he was released. But we thought that he had perished. Sometime later I found out that Aleksandr Razgonin had returned alive, but was living in a very difficult conditions and working at a garage. I went to Ivan Ivanovich Borzov and told him all this. Borzov, in turn, went to the Fleet Commander. We went there together, but I had to wait in the reception area, while Ivan Ivanovich spoke to commander. As a result, Razgonin was restored to his former rank and his former position, so he began receiving his military salary.

– He was not stripped of his HSU title?

No. He was simply forgotten about. They threw him from the military ranks. His active service time was low and pension was low too. He was a very gentle, standoffish, and modest man. He did not know how to push a queue aside. A nice man.

– What about alcohol during the war?

I had a line in my evaluation reports – drinks a lot, but with disgust [laughs]. I was never too keen to drink, but was not a stranger in a company. I could hold on pretty long, and never was completely drunk.

– Did you fly under the influence of alcohol?

No, never. We never flew drunk. But in 1944–45, there was a decanter with spirit in our officers’ mess, so after we returned from a mission we sometimes would drink to relieve the stress. Unfortunately, a lot of us couldn’t stop when war ended.

– Old pilots used to say, that those pilots who flew recklessly during war often were killed in air accidents in peace time. Could you confirm?

Yes, it was a common problem.

– Were there problems regarding nationality?

How could there be?! Aleksandr Gagiev was an Ossetian and, despite a difference in characters, we were very friendly. He liked women a lot, chain-smoked, drank a lot. I, on the other hand, was monogamous, never smoked and drank alcohol only when the situation required.

A-20 crew. Left to right: Gagiev, Demidov, Sokolov (crew gunner, shot down one Bf.109)

– Which colors were used to paint aircraft tactical numbers in your regiment?

Yellow. My bort number was yellow “6”. Then my number was yellow “30”, since “6” had been shot down by our own AAA. I flew “30” till the end of war.

– Wasn’t there a possibility of confusing your aircraft with German planes that carried yellow friendly recognition elements (FRE) because of this color use?

No, it was not so much of a problem.

– Were there FRE on your planes? A “cap” at the fin, or perhaps the rudder was painted in a special color? Some nose art?

No, nothing like that; only the tactical number.

There were things like that in civil aviation. After the war I worked there. I resigned and had to move from Leningrad to Moscow, because my wife was sick. 15 times she had pneumonia in Leningrad. The doctors told me, that if I did not take her to other region, she would die in a year. I went to the personnel department, wrote a report and resigned. I began working in the Moscow Civil Aviation Academy.

– Were aircraft numbers issued according to some rules?

No, they were different. We just used the ones that we received. Who wrote them, I do not know. We were surprised by them ourselves.

– What was the attitude toward decorated comrades and those who received the Hero title?

Normal, ordinary. There was no jealousy or any urge to get one. If we sank a merchant vessel, we would usually get an Order of Combat Red Banner.

– I spoke to a HSU shturmovik pilot:

“Were you happy to become a Hero?”

He replied:

“You don’t understand what you are talking about. When I received it, I had no idea how to get rid of it. From then on I got all the most difficult and dangerous missions, because they believed that I could do anything.”

Yes, very close…

– Do you remember your first combat mission?

Like it was yesterday. Our 51st MTAP was tasked with the destruction of an enemy assault force in the area of Luga Bay. It was a real story.

When we breached the blockade and cut a railroad by means of which the Germans in Leningrad area supplied themselves, they had to bring in supplies via sea, and decided to build a naval base in Ust-Luga. For that they tried to effect an amphibious landing there. It was where I hit my first target by skip bombing, in a first mission.

We took off from Klopitsy in a four-ship formation and attacked the convoy from the shore line. When commanders assigned the mission, we were ordered to attack from the open sea. We disobeyed, but the Germans did not expect us from that side [landward]. If we would have followed the prescribed directive, we would all have perished.

– In which Fleets did you serve?

Only in the Baltic. But I served on temporary duty in all others, except the Pacific Fleet.

– Did you meet Preobrazhenskii? [HSU Ye.N. Preobrazhenskii, well known commander at several levels in Baltic, Northern, Pacific Fleets; commander of all Soviet naval air forces from 1950–62. Ed.]

Yes, I did, but not in a regiment commander role, rather when he was the Baltic Fleet Air Forces commander. Smart and intelligent man.

– Did you fly with him?

No, I did not. I had to fly with Borzov a lot.

– What was your attitude toward the Allies and the Second Front?

We were not concerned about them at all. At first we waited for their help, and swore that they wouldn’t help us. But later we were indifferent.

– How about when they finally did open the Second Front?

We spat on them then, too. Absolutely indifferently.

– When did the war end for you? When did you stop flying combat missions?

After 9 May, 1945, we kept flying combat missions for two month, looking for enemy ships in the sea, sinking them. We ended the war completely in Latvia in 1949.

Ilyushin Il-4. North Fleet museum

– Were these missions accounted for as combat ones? The war was over. How seriously did you look after your score and awards? Were there any monetary prizes for successful crews?

There were clerks who did all the counting and writing. We were not bothered at all. There were some payments, but not a lot. For each merchant we got 3000–6000 rubles. Some of our pilots used money for wallpaper. A loaf of bread cost more then.

– Nowadays, historians like to discuss how much this or that person got without understanding how much money really was worth back then. Did you send money to your relatives or to the “defense fund”?

Money was collected for different funds. We mostly didn’t send money to our relatives, because they were cut off from us.

The most dangerous day in my life was when I went on vacation after the war. My relatives lived 18 kilometers from Kharkov, where they had built a house, instead of apartments in Kharkov. There was famine there, while we had some food. I gathered two suitcases of food and went to Kharkov. There were regional trains before war, but they were not working immediately after the war ended. There were no cars or trucks either. So, I thought, how am I going to get there? So I went to the railway station with these two suitcases, got between two freight cars and traveled standing on the buffer between the cars. While train was going slowly, everything was fine. But then it gained speed! I was terrified, having to balance between cars with suitcases in both hands… I jumped off the train while it was still moving; luckily, I was unharmed. That was the most terrifying and dangerous moment in my whole life!

– Germans received metals, iron ore and ball bearings from neutral Sweden, and this materiel was brought in by Swedish ships. Was there any difference for you between German or Swedish ships?

No, there was none. We attacked and sunk Swedish ships, too. We drowned them near the Swedish coastline.

– So you operated in Swedish territorial waters?

Yes, we flew there, identified and sunk their ships there. They did not present any objections [laughs]. Swedish fighters took off and flew near, but did not engage us.

By the way, I remember there was a large German airfield in Pyarnu, which we later captured. The Germans had Messerschmitt-110s there. However strange it may seem, we were quite friendly to them. When we flew over them, we rocked our wings; they would take off, fly round us and swing to us. But that was an exception, of course. Our forces were pretty similar, both had twin-engine airplanes, and no one wanted to die at the war’s end. So we flew straight to the west through Pyarnu, while routes to the north or south were much more dangerous.

– Sober calculations on both sides saved many lives. But a lot were still lost… I can see that in some photos you and Gagiev look alike – with moustaches.

There is a real story behind them. At the war’s end, we flew to Leningrad for torpedoes. The trains were not going yet, nor were other means of transportation available. We had to bring one or two torpedoes for ourselves. So we had to fly to Leningrad once again.

Just one month before that, my pilot Aleksandr Gagiev got married. He had an excellent wife, who lived with her father, mother and sister in Leningrad. When we came in, we stayed there for a night. In the morning we were awakened by completely unknown woman. I asked:

“What happened?!”

“The war is over! Get up!”

We got up. We had an agreement – when war ended, we would shave our moustaches off.

He had had a moustache all his life, while I never had one. I told him once, recklessly:

“Your moustache is not growing.”

He was offended:

“Your moustache is not growing, either.”

“I will get it twice as big as yours in a month.”

“They will not.”

“I’ll make you a bet. If I grow mine out, at the end of war we both will shave them off. You and I.”

I took up the challenge. We made an agreement that we would shave them off when the war ended.

– When did you have this argument?

At the beginning of 1945. In the end I grew such a moustache, that it did not allow me to eat properly.

So, we went to the barber shop at the Moscow railway station to shave. When we were finished, we walked out to the station plaza. We were wearing our Gold Stars, but no other awards. People lifted us in the air and carried us through all Nevskii prospect. I will never forget it!

– When did this happen?

On 8 May, when the end of the war was announced.

– When you were transferred to 1st Guards MTAP from 51st, did you receive a Guards title straight away?

No, a bit later. Even though Borzov respected us after that flight that I described earlier. Then we became Borzov’s favorites. He sent us, captains and lieutenants, to lead entire squadrons instead of him. He trusted us. Aleksandr Gagiev was an excellent pilot; I can compare him with Gromov [HSU M.M. Gromov, who established a world-record flight in September 1934] or Chkalov [HSU V.P. Chkalov, who participated in record flights in 1936–37, including a non-stop monoplane flight over the North Pole from Moscow to Vancouver Barracks, Washington]. In the air he listened to me and paid attention. Borzov liked him and tried to place him in different command positions, but Gagiev did not become a high ranking commander. He was not successful in science, either. He graduated from the Academy after the war, but just barely.

– Veterans used to say that Borzov rose after the war due to Vassilii Stalin’s protection.

I knew Vassilii Stalin too. We were based at the same airfield in Shaulay. Our regiment and his division were based there. I went to his commanding post several times and spoke to him. My opinion – smart, good pilot, but spoiled by his father’s ass-lickers.

– There are two opinions about Vassilii Stalin: a sloppy or, on the contrary, a very good commander.

He was an excellent commander! I had an opportunity to see him act in most difficult situations. There was a case, when a surrounded German tank regiment attacked our airfield at Shaulay. Vassilii Stalin organized the defense; on his order, airplanes were directed toward the enemy, and thus we managed to repel the attack. All thanks to Vassilii. Just imagine – we repelled a tank attack only due to his steadfastness and organizational abilities.

Vassilii Stalin was Borzov’s friend; they spent a lot of time together. Once Vassilii asked Ivan Ivanovich to exchange one of his fighters for one of our Bostons. It was supposed to be done officially. Stalin had an old, slow Douglas [C-47]. Because he had to visit Moscow very often, he wished to get our plane, which was twice as fast. But someone reported the exchange to Stalin, his father, and they both were reprimanded.

– You mostly were escorted by 21st IAP?

The 21st IAP under the command of Pavlov and 14th Guards IAP under the command of Mironenko.

– Vladimir Tikhomirov from 12th IAP told us that at the end of war Army fighters were ordered to cover Navy shturmoviks and bombers.

I remember that, but they were worthless. Naval pilots were used to fly over the water, while VVS pilots were not. Once they reached shore line, they began whining over the radio:

“Let us go. Release us! We cannot fly here.

It was a stupid idea to ask them to escort us. They could get lost at low altitude.

– Was there a test Boston in your regiment equipped with radar?

It was Borzov’s airplane, and our crew tested it. We clearly understood that this radar was worthless, but still wrote a positive report. There was a need to kick our technology a little bit forward, which is why we wrote a positive report.

– When did this happen?

In 1944.

– These radars were tested in all fleets, but pilots reported that they were more of a problem.

Yes, that’s true. I wrote a positive report, even though I should have written a negative one. It was not ready yet. But if we would have made a negative report, the project might have been halted completely. So I carefully described all the problems that we encountered, but made a conclusion that work should continue.

– Did you participate in the Konigsberg liberation?

Yes, the fighting there was heavy. For the first time we used high-altitude torpedoes there. We dropped three torpedoes from 5,000 meters into the bay of Danzig. Shturmoviks reported that one of our torpedoes hit a merchant, even though it shouldn’t have. These torpedoes ran in circles and were used to block convoy movements, allowing mast-top bombers and torpedo-bombers to strike more effectively. Our task was not to sink, but to block a convoy from dispersing. But in the end, as I mentioned, shturmoviks reported that one ship was sunk by a high-altitude torpedo.

– What kind of opposition did you met over Konigsberg? Were there any fighters?

There was almost no opposition to us in the air over there.

– When you were based at the airfields in Germany, did you see German equipment there?

No, when we landed at new airfields, everything had been cleared.

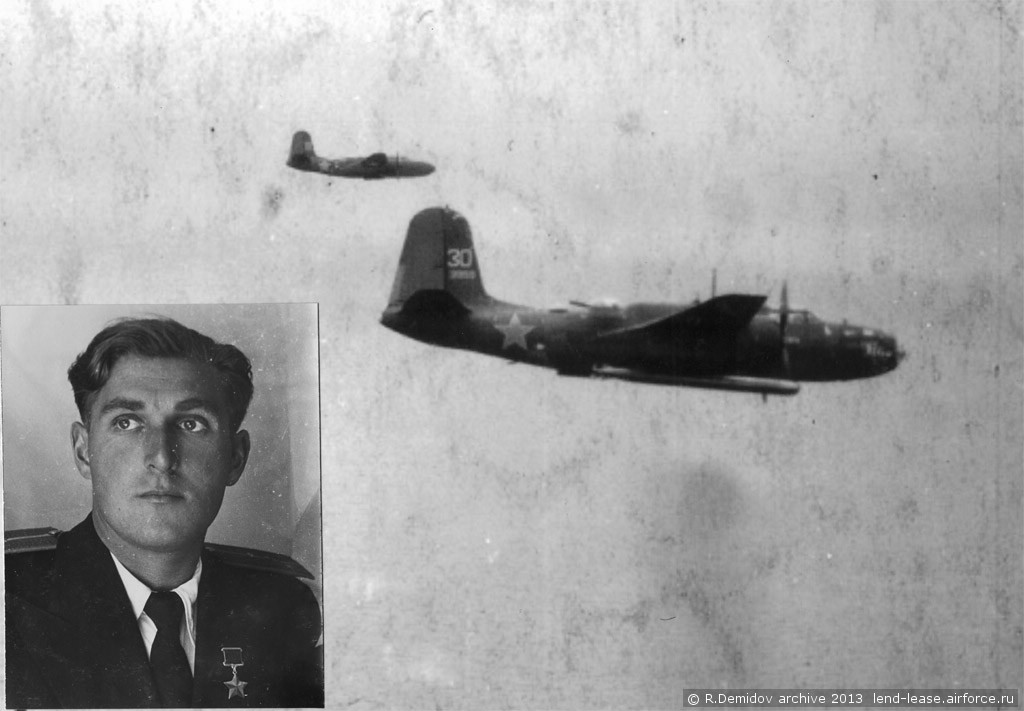

Here is our “30” at the airfield, and here is our Masha, from photo lab. When we were going to fly, she gave us a photo camera, and we made photos from the air. We had to fly reconnaissance missions, make photos of each ship that we encountered and make photos of the strike. It was done with ordinary hand cameras.

– Did you have built-in cameras?

Usually, we took ordinary cameras, although I recall that we carried special camera when we made a strike against Libava airfield.

– How durable was the Boston?

It was very durable. Once we were given a mission to attack German shipping in Riga Bay. We took off… We attacked an “ordinary merchant,” but it was a decoy ship, with a lot of Oerlikons. We took some heavy hits; our airplane was torn to pieces, full of holes like a sieve, and without a tail. We barely made it home.

– What do you mean “without tail”? How did you fly it, then?

The fin was torn away completely, while there were remains of the stabilizer and elevators. It was hard to fly it, but we made it. Aleksandr was a great pilot, he brought us home.

– Were you afraid in war?

No, never. We thought about it as a sport. Even combat missions were sport to us. I was much more afraid on that train, fearing that I will die stupidly.

– After the war, you studied at Monino Academy and remained there as an instructor?

Yes, I studied there and became a teacher. I taught for six years before we moved to Leningrad, when the Aviation Department was opened in Kuznetsov Academy.

There used to be a Navy Aviation section in the Navigators Department at Monino Academy, organized in 1947. We were the first there. After us, there were several others. Later, when they recruited for the Naval Academy in Leningrad, they stopped selecting naval navigators [for duty] at Monino.

– Were you in a “Golden Horde”?

Almost. I was at the navigators’ course, while “Horde” was at the command course, and consisted almost completely of HSUs or twice HSUs. There were fewer HSUs among us navigators.

– I can see that you have original photos with Gagarin. Did you meet him in person?

Yes, I did. It happened at the VVS Academy in Monino. We were preparing them for space flight. Cosmonauts were brought to us and we taught them navigation, not too deep. It was very important for them, so they listened to us with great attention. They were nice guys, and Gagarin was a very modest, good lad.

I took several photos of them in Monino. My wife had taken his picture, but it was taken away. Great picture! This post card was made on its basis. I kept it, and later Gagarin signed an autograph for me on it.

– What do you think about his death?

They shouldn’t have flown. There was some human error; the airplane seemed to be fine… But the exact reason was not found.

– When were you invited to the navigation department in Leningrad?

In 1963. In the autumn of 1964, I became the faculty chief. There was no aviation department in the academy before that. When it was created, I was invited. The temporary chief of the department was Ivan Gavrilov, but after my arrival, I was given this post.

– Why you?

It’s hard to say, perhaps because I had more experience in navigation. Gavrilov was a navigator with a very narrow field of expertise. Like Gregory Avanesov, he was an anti-submarine warfare (ASW) unit navigator, and flew with an MBR-2. They had the very specific task of finding enemy U-boats with special equipment and attack them with special weapons.

Rostislav Demidov in civil aviation

– What were the relationships between the tactics and navigation faculties?

Excellent. The chief of the pilots department was Balabasyov. We studied at flight school together. But I had very little contact with pilots, so I remember them less than the navigators. When we conducted customs and traditions work with them, we had to nursemaid the wives when they got to arguing among themselves.

I remember the chief of the academy, Fleet Admiral Orel. For some reason he liked me. If he had any questions regarding aviation, he would summon me. For example:

“My mother-in-law is flying out of Orenburg today. When I should meet her? Can you calculate?”

“Any additional data?”

“No.”

So I went to my office, called the airport and asked the information desk when the flight from Orenburg would land. I returned with a report. He announced to all present:

“Look – Demidov knows everything!”

I also witnessed how he dismissed one of the sailors, threw his hat down and stomped on it; another time he threw the telephone and also stomped on it; and another time threw an admiral out [of his office]. He was an original, but for some reason he liked me.

– Can you say anything about Zhitinskii? [Lieutenant-General of Aviation N.P. Zhitinskii – ed.]

Zhitinskii was great, smart man! He was purged, spent some time in jail. Zhitinskii was no worse than Borzov, but softer. I knew him and his family well. He did a lot for me. He was a respectable, kind, and remarkable man.

– Were you sorry to leave Leningrad?

I always loved this city, and I still do. Almost all my life was connected to it. If not for my wife’s health, I wouldn’t have left it. But we always called it Peter.

– Two final questions. Which missions did you most prefer, and which did you most dislike?

We hated to fly after some stuff for political officers, and we just loved to fly to Leningrad to pick up torpedoes.

– What surprised you the most during war time?

It’s hard to say. Let me think… I’d say, that Borzov decided to transfer us to his regiment, it was very important for us! 51st regiment was “condemned,” and we clearly understood it, there was no one to teach us there. In 1st Guards MTAP were a lot of men who could teach us. I’d say, this had the most positive effect on us.

Rostislav Sergeevich Demidov, 2010

Appendix: Photographs from the Naval Aviation museum (St.Petersburg)

Interview by Galina Vabischevich and Oleg Korytov

Editors Galina Vabischevich and Vasilii Silantyev

Translation by Oleg Korytov and James Gebhardt