Part 2. Korean War

Editor’s comment: Although the events described in this interview are not related to Lend-Lease, the editors feel that describing Korean combat experience of pilots earlier involved in flying Lend-Lease aircraft, will be beneficial to our readers.

Let’s move on to Korea. In Korea did you fly the MiG-15, or did you already have the MiG-15bis?

In China we were training Chinese and Korean pilots on the MiG-15, and we conducted combat actions in the airspace over KNDR [the Korean People’s Democratic Republic—North Korea] in the MiG-15bis. As part of the same 28th Guards Fighter, Order of Kutuzov III Class Regiment.

Did you replace someone there? Or were you in the first cohort?

No, on this occasion we were not replacing anyone. There were already propeller-driven aircraft there—night fighters. But I did not see them. Our regiment was based in Andun. At that time they were just building the Myaogou airfield. Kozhedub arrived in Korea with his division. He landed at Andun airfield. Lobov’s division went to Myaogou.

Tell us, how did the Korean War begin for you?

The long version or the short version? I guess it’s my choice. I was at periodic training for fighter pilots for flying in bad weather, on instruments, and at night. This was at the Savasleyka center for combat use of the aircraft (similar to “top gun” school) The regiment sent me there sometime in March.

At this time, this was in 1950, the Korean conflict began. Initially the Koreans advanced, and drove the South Koreans almost to Pusan. Then the Americans intervened.

Pilots from Lobov’s division were also attending these courses. I recall that one of them was Perepletchikov. He learned that their division was leaving on temporary duty to China, and went to the superiors. He requested that he be permitted to test out of the course early and return to his regiment. He soon left. A division from Yaroslavl was also sent to the East.

I completed the training. In addition, I will tell you, only two pilots—and I was one of them, the second one was the commander of Savasleyka Center, who later became commander of the 8th Army of PVO in Kiev, I just can’t recall his name—received the rank Pilot First Class. The remaining pilots were designated “second class.” I completed a MiG-15 flight at night in such terrible conditions that I was barely able to land.

What was your rank at that time?

Senior Lieutenant. The courses were completed and I returned to Kalinin. I had gone there in the winter and returned to my unit at the end of June. It was summer—hot. I got off the tram that delivered me to the airfield and was walking, carrying my suitcase and greatcoat. The division commander approached me in his GAZ. My appearance surprised him. “Ovsyannikov! Where are you coming from?”

This was a jeep-like vehicle, named from its factory of production—Gorkiy avtomobilnyy zavod. [JG]

I stopped and thought to myself—did I forget to greet him? This happened sometimes, that you have to salute your senior commander even if he is in a vehicle. I said, “From training courses, Comrade Colonel! I just completed them.”

“OK, go immediately to the headquarters, and tell them to include your name on the list.”

What list? Well, I continued walking, and met some of my comrades along the way. They were all in civilian clothes, and drinking beer at a kiosk. At that time we had beer in the cafeteria flight crew canteen. They also sold vodka from the cafeteria.

In an aviation unit?

Yes, in an aviation unit. We did not drink to excess. We knew what and when to drink.

In short, I arrived at the headquarters and reported to Matvey Matveevich Pestov, the chief of staff. “Comrade Major! The division commander met me and told me that you should include me on the list.”

“I have to redo the list again!”

I said, “I don’t know. I am only carrying out an order. What is the list for?”

“Temporary duty in China.”

Well, we knew that. The American spies also learned where Lobov’s division had gone. The Western nations covered it in their press, so the division was diverted to Vladivostok. In its place they were sending our 151st Guards Fighter Division (GIAD) to China.

Did they have to force anyone to sign the confidentiality disclaimer?

I don’t remember.

Before your temporary duty, how many flight hours did you have in the MiG-15?

Perhaps 15. Including my night hours. The regiment’s other pilots — no more than that. I had more because I flew more.

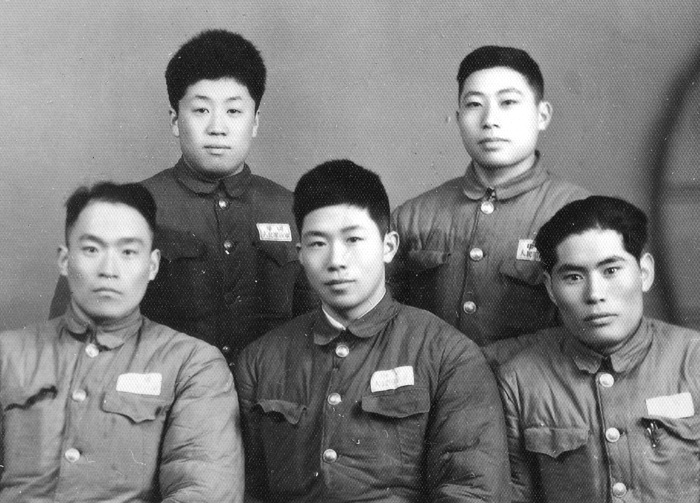

We went to China by train; our MiG-15 aircraft were supposed to come right after us. While we were getting organized, a week later our trains with aircraft began to arrive. We test-flew the aircraft after they were assembled, and they assigned us the mission to transition the Chinese pilots. These Chinese pilots had completed school in the Yak-11, a propeller-driven aircraft.

These were the pilots we were to transition. And not on a dual-control MiG, but in a dual-control Yak. Altogether, we had six or seven instructors, I think.

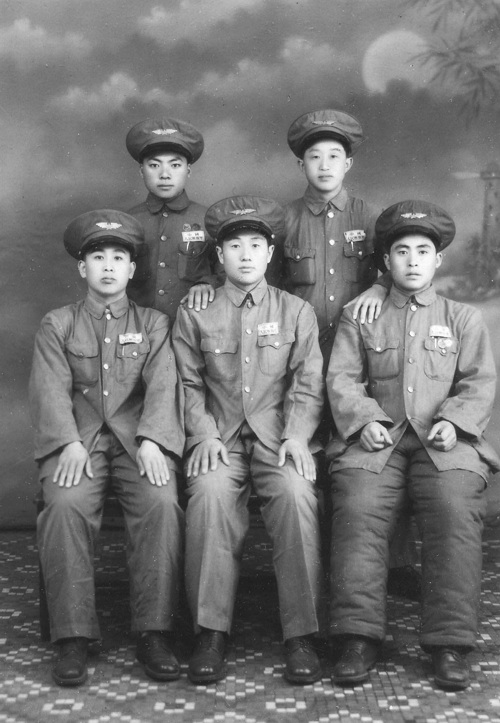

Chinese pilots before transition training

As far as piloting techniques, were they different for a Yak-17 than for a MiG-15? Or were they pretty much the same?

You must understand that there are differences between any two airplanes. At the same time, they have things in common. Their speeds, of course, were different. And landing with a three-wheeled aircraft was simpler than on an aircraft with a tail wheel or skid.

In your opinion, did the Chinese have problems with moving from the training Yak-17 to the MiG-15?

Almost no problems. They were studious pilots. They executed instructions literally and without question.

Chinese cadets

It’s generally understood that they normally eat less than we do. Were there occasions when they lost consciousness in flight?

I will tell you about this later. We began to transition the Chinese pilots. We flew and we flew and we trained. In one of these flights, the regiment commander, Kolyadin, who was supervising that flight, transmitted to me: “115—after landing, report to me!”

Just like at the front, we had callsigns there. All of us had our own callsigns. I walked over to him, and the division commander was there, smiling. He extended his hand: “I congratulate you! With the rank military pilot first class, and with promotion to the rank of captain!”

They did not give everyone first class at that time.

I had already served more than enough time in grade to be promoted, but my position did not give me the right to receive the next higher rank. First class did give me the right for one step in rank higher.

Well, so now I was a captain. I continued to train, and now already the regiment’s pilots had begun to fly from Mukden airfield and conduct aerial engagements. I will tell you about that after I finish this part of the story.

On another occasion, “A directive came in to recommend the regiment’s personnel for promotion, for successful execution of the mission.”

So my division headquarters, and the regiment as well, again sent a recommendation for the rank of captain. Another time, already after the beginning of combat actions, they again summoned me to the command post. A directive concerning promotion had come in. Again the division commander smiled. Aleksandr Sapozhnikov was smiling again.

“I congratulate you on reaching the rank of major!”

I don’t know how this happened. But it happened.

Did you have to drink for your stars, as a general rule?

No, no. We drank for other reasons. So I became a major, and quickly they appointed me as a squadron commander. We were flying our first combat sorties from Mukden. It was far away. We did not have drop tanks. We would fly out and hang around for five minutes, and then fly back. Later the Chinese began to slap together drop tanks, from tin plate that was intended for tin cans. They were a piece of trash. You took off, and behind you was a trail of kerosene coming out of your tanks.

In the literature, you constantly encounter assertions that our pilots were ordered to converse with each other in Korean.

I will tell you the real story. This all happened. It actually happened. Pepelyaev talked about this and more. When we began to fly combat missions, we were required to study the Chinese language. I passed an exam in the Chinese language.

It began with one, two, three, and later “chzhou yuan,” then some other kind of “yuan.” Left turn, right turn. Well, in general, we studied the required aviation terminology. Perhaps we did not pronounce it correctly, but they understood us. When we began to fly, they said to us, “You need to limit conversations in Russian.”

They did not forbid us to speak Russian. But they said to us, they warned us, they advised us. No one reprimanded us or cursed us. And, of course, we spoke only when necessary.

From right to left: Sosna, regiment commander’s driver-Korean, Ovsyannikov behind the wheel, Grigoriy Timofeev Garkavenko

Did you transition the Chinese pilots, and later move to Mukden and yourself begin to fight?

When they began to put pressure on us, they took the training mission away from us. They made the Mukden airfield ready and our entire regiment flew there. Our first primary mission was to cover the bridge and dam at Andun, the Supkhun hydroelectric station. I don’t remember now, but I think it was January or February [1951].

Were you able to fly familiarization sorties in the area of combat actions?

As soon as we moved there, without any familiarization flights, we began combat patrols from the first day.

At what altitudes did our air forces operate?

At various altitudes. We intercepted Shooting Stars at low altitudes—500 to 1000 meters, and the B-29 somewhere on the order of 5,000 to 6,000 meters.

How often did the Americans fly against the bridge?

I can’t say how often. I had about 50 sorties there at that time, I don’t remember exactly. They sent us up fairly often, but more often we would hang out in the air. Sometimes they vectored us against fighters. I had perhaps five or six engagements with bombers there.

How were pilots selected for temporary duty in China? Did they simply send the entire regiment? Or was there some sort of selection? Or did pilots go as volunteers?

No, no. As volunteers. If you said, “I’m not going!” no one would send you. Some of our pilots — one or two — did not go. Why? I can’t really say.

What kind of mood did you have? How was your morale?

What kind of morale? Where they send you, you go. Wherever. It’s not the same as now.

One encounters assertions that ostensibly our pilots were not so eager in their first encounters with the Americans. In connection with the fact that just prior to this, they had been our allies. Later, when we began to suffer losses, we began to fight back in full force. Or did we genuinely fight with them from the beginning?

I don’t know who puts out this rubbish. If you take off, and someone shoots you in the ass with six machine guns, what kind of friend is that? No, we considered them to be enemies. Right now I consider America to be our enemy. Earlier, during the Great Patriotic War, I did not consider them to be genuine allies.

Whose aircraft armaments were better?

Soon after the war, the Americans in a book expressed an opinion of their pilots, who said about the MiGs, “If only we had such armaments!” I will continue. For ome time we sortied frequently. Around March 1951, they gave my squadron a rest. At that time we were housed in the palace of some Emperor Pu-I. It was an enormous palace, near Andun, perhaps 10 kilometers from the airfield. In Andun, we had right away begun to conduct combat actions—patrols. In the morning, only in daylight. We did not fight at night.

Two squadrons went to the airfield and we stayed behind. We each did our own thing—some played chess, and so on. Suddenly we heard the drone of aircraft. Of course, I picked up the telephone and asked, “What is going on? What? What should we do? Leave or stay here?”

They told me not to leave, and explained that [F-80] Shooting Star fighters were headed our way. Normally one could see far away, almost always away from the sun; contrails were visible. One four-ship flight, a second, and then a third. We would gain altitude over Chinese territory.

Someone was talking on the television, and was talking about how we shot them down over the airfield. When we were there, I recall a single case when the Americans crossed the Chinese border. I will tell you, there had been no border crossings before this. Normally we fought over Korean territory, but perhaps they just jumped the border. They flew across and then left.

There was a balcony around this palace. We went out onto the balcony. It was a large brick building. The roof was curved a bit.

So we are watching, and someone shouted, “Look, guys! Some MiGs are chasing Sabres at the airfield!”

Behind them was a pair. It was difficult from our vantage point to determine who was who. Suddenly we heard a burst of fire, like a tearing sound: “Tr-r-r-r-r!”

“Guys! That’s the Sabres chasing our airplanes!”

They fired a burst, then turned and departed. I got on the telephone again and asked what was going on. They said to me, “A Sabre hit and damaged Kolyadin.”

[This event occurred on 12 March 1951. The pilot who damaged Kolyadin’s aircraft most likely was Lieutenant Colonel Glenn Eagleston, commander of 334th Fighter Squadron, 4th Fighter Interceptor Wing. I.S.]

His wingman, Bushmelev, broke off and returned to base. Kolyadin arrived, as usual, went in for landing, and they shot him up. Thirty-two holes in his aircraft. There were holes everywhere—the tail pipe chambers, hydraulic systems, landing gear—he was not able to lower his gear, and landed on one wheel. But land he did, alive and healthy.

Did they repair the aircraft or write it off?

They repaired it. If somehow a pair of 23mm cannons rounds had hit the Sabre, it would not have been able to land.

Can you give us an example of our cannon strikes? Barsht said this about our cannons: “Was there any shortcoming? Here comes a Sabre, attacking someone. You lay out a burst of barrier fire, and it passes through between several shells.”

Well, how to say this mildly—he is lying. Some burst of barrier fire. Try to deliver it at a velocity of 900 kilometers per hour. And than try to see if he can pass through it. I don’t know. But I didn’t go around with heroes…

Tell us, please, did you work against ground targets?

No, only in the air.

The Americans write that they did not see MiGs over the ocean; did our commanders forbid you to fly out over the water?

It’s all invented. They said to us, “Guys! Do not fly over the Yellow Sea. If they shoot you down over the Yellow Sea, you’re done for! No one will come to your aid. The Americans are there.” They did not need to forbid it; they simply advised against it.

So there was no concrete prohibition?

There was no specific prohibition. [The prohibition was quite strict! And it was strictly monitored. As soon as they observed on radar from land that someone had crossed the coastline, they gave a command by radio to come back to land and return to base. They did not punish pilots for these violations, since a strict command came from the command post not to cross the coastline. They cursed only those who heard this order but did not execute it, but such violations seldom occurred. It happened in the heat of the moment that our pilots went beyond the boundary of the coastline, but with an immediate “reminder” from the command post they just as quickly executed the order to come back over land. Such excursions were strictly monitored! Perhaps this never happened with Ovsyannikov or they simply never violated this order and they never had occasion to be reprimanded for it. Therefore he has no memory of it. I.S.]

Did you cross the front line?

This also was not recommended.

Only “not recommended”?

They did not recommend it. Where was the front line? How was it marked?

The devil knew its location; there was hardly any line drawn on the ground, the more so in the mountains.

I will tell you about an engagement that I conducted with some B-29 bombers. They scrambled us and then informed us of the following: “Group of bombers. Look, they are there!”

“Where?”

“They are close by!”

I did not see them. Then “ground” gives the command, “Cease combat mission. Cease combat mission, return to base!”

At this time they appeared. Below us. They had already turned toward home. And I already could see the coastline of the Pacific Ocean. I radioed: “I see them!”

“Ground” did not issue any commands, so I decided to attack. While I was catching up, you understand, some time elapsed. Then I dropped down and we attacked them. I hurtled straight past the wings going down hill. The speed differential was significant: I was going somewhere around 1,000 kilometers per hour, and they were flying at 600 — 400 kilometers per hour difference.

Did you see your strikes?

Of course not. I fired a burst and radioed: “Make a quick turn and go back to base!”

I ordered all the pilots, “Do not assemble! Move independently!”

To assemble meant expenditure of more fuel. We gained altitude again and moved to our base. When we were perhaps 90 kilometers from the airfield, suddenly my wingman — Tolya Bezmaternyy (strange name [it means “motherless” in Russian] — he was a short, red-haired man) — transmitted, “I’m ejecting!”

Immediately I began to think, “How far did we fly?” I was the commander, and they ordered me to return! I did not execute the order!”

These thoughts were running through my head when I came in for landing. I touched down, taxied, parked in my spot, and looked around. One aircraft was taxiing, another was on final. There 12 crews in all, 11 had landed and one had bailed out. One combat loss. Suddenly, “Request permission to land? Support my landing…”

This was Tolya, coming in without an engine. He touched down, rolled out normally, then taxied. I said to him, “Were you trying to frighten me? Didn’t you say that you were ejecting?”

“Comrade commander! I looked out, and all around me was water. I thought about it; the Chinese would search for me. But the Koreans were also pressing in, and if they picked me up: who am I? Russian or American?”

While his fuel indicator hovered around zero, the engine was still working. Then he glided. This was the second such incident in our regiment. The first pilot’s name I forgot. The squadron zampolit intercepted a reconnaissance aircraft. He also ran out of fuel, and also glided in from 9,000 meters [altitude] and landed at the airfield.

[The engagement described here with the B-29s occurred on 25 February 1951. The pilots of Ovsyannikov’s group scored four downed B-29s. They landed at their airfield on the last drops of fuel. I.S.]

When did the Sabres appear?

The Sabers showed up almost right away. Yes, they were there immediately. But initially there were very few of them. Later they began to fly more often. Our first engagements from Mukden were with F-80 Shooting Stars, F-84 Thunderjets, and Corsairs. And even the propeller-driven Mustangs. [The first encounters between Sabers and MiGs occurred on 17 December 1950, and these were the pilots of the 29th Guards Fighter Regiment. On both occasions, the engagements ended without results for either side. The pilots of the 28th Guards Fighter Regiment did not encounter the F-86 until 11 March 1951. I.S.]

Can we ask a completely stupid question?

You can ask a stupid question, and you will get the same kind of answer.

How did you fight a MiG-15 against a P-51 Mustang?

Very well. Because I was the “king,” or whoever sat in my place. At any moment I could break away from him or do with him what I wished. Whatever speed he maintained — I could match it with the MiG-15. I think the Mustang was capable of 600 kilometers per hour. The MiG-15, it seems to me, was quite maneuverable.

It was one of my favorite airplanes. I did not like the MiG-17. The MiG-19 was even worse—solid like an oak tree.

Let’s return to Korea. What other aircraft types did you encounter?

The F-84 Thunderjet.

Did it have straight wings or were they already swept back?

They were just slightly swept back, like our Yak-17. [At that time the Thunderjet only had straight wings; therefore our pilots nicknamed it “the cross.” The G modification appeared in 1952; this variant had the backswept wing, but the pilots of the 28th GIAP naturally did not encounter it. I.S.]

When you shot something down, how was it confirmed?

After we conducted this attack, my wingman brought back a bullet in his wing leading edge. My wingman was the zampolit, Nikolay Pronin.

Is he the one who glided in without an engine?

No, it was another zampolit. I have corresponded with him. I think he has also passed on. What were we talking about?

[The zampolits in the squadrons of the 28th GIAP were: Senior Lieutenant Mikhail Petrovich Nasonov, and after his death Captain Ivan Filippovich Krivakov became the zampolit. Was it Nikolay Grigorevich Pronin, the zampolit for 3rd Squadron, who landed without an engine? I do know that Nikolay Alekseevich Nekrasov from 3rd Squadron landed in November 1950 at the airfield and heavily damaged his aircraft. Perhaps this is who Ovsyannikov had in mind. I.S.]

How was this mission scored?

We made the attack, came home, landed, and I reported, “We fought an engagement! I attacked four B-29s.” That was it.

In addition, the enemy spoke freely and put out over the radio: “At such-and-such location, our bombers were attacked by MiG-15 aircraft. As a result, one aircraft fell into the ocean. A second aircraft was damaged and crashed upon landing on Okinawa.

Then our gun-camera film was developed, and we looked at it. It showed me opening fire at very close range. And the others—some did and some did not. I got credit, that’s it.

Did you get credit for any Saber kills?

Yes. When I fired up a “cross” [F-84 Thunderjet], I saw that when I fired a burst, something flew off the wing. He went over like this [gestures] and then I lost sight of him. What he did after that—I don’t know. I departed upward as usual. [Officially, Ovsyannikov was credited with one F-86, which he shot down on 30 March 1951. The other two fighters that were credited to him were F-80s. I.S.]

Were the battles quite heated? Or did they vary in intensity?

If they were with fighters, they were always normal. You put everything into it.

So one could compare it with fighting the Germans?

Yes, you could compare it to the Germans.

Who was a more steadfast foe, from your point of view?

I really can’t say. Who here is steadfast? Who? In what? If you got behind them, they turned; if they got behind you, you turned.

In general, were the American pilots good?

Yes. They had an enormous amount of flight hours.

Generally speaking, when you were in China, were you preparing for combat?

We were preparing. In our training battles we emphasized cohesiveness in group combat and performed simulated aerial battles.

What were the largest American formations in the air?

I recall, I think, 45 bombers at one time. Against the dam. This was before Kozhedub replaced us. They had a very large covering force of Thunderjets. They had direct escort. There was another group of fighters whose mission was to “clear the airspace.” This group was made up of Sabers. There may have been as many as 150 aircraft in the entire group. We put up, I think 18. That’s all we had available.

[This was on 30 March 1951. On this day, 16 aircrews from the 28th GIAP and 8 aircrews from the 72nd GIAP sortied. They encountered a group of 24 B-29s that were escorted by 40 F-80 and F-86 fighters. I.S.]

In the end, did many Americans make it to the target?

Not one of them reached the target. I don’t know how many of them there were. They told us that the total was 150.

I do not recall how many of our pilots scored that day. It was such a tangle, that I don’t know who scored what.

Did the Americans report the results of the raids on the targets you were covering?

They did not report. But they were unable to bomb the dam.

At any time did you use the capabilities of the sight on the MiG-15? How did this automatic sight work?

When you laid the sight on an aircraft that had an angle of displacement, the aimpoint shifted forward. You aim at the aircraft, and the sight calculated the lead angle. I can’t say. I did not use the sight in the fixed mode.

Many of our pilots, and the Americans as well say that it was simpler for them to use the fixed sight.

Perhaps, perhaps.

Was the F-84 Thunderjet capable of flying with the MiG-15 in a maneuver fight?

I did not dogfight with them. They came in, and I attacked them when they were bunched up. Like us during WW II, they were escorting their bombers. We had two groups: one group of immediate escort, and another so-called maneuver group, which engaged in combat. They did the same thing, used the same tactics. Those that were flying immediate escort were tied to the bombers; they were required to protect them. They only fended off attacks. And those that were covering this group could freely engage in combat.

Did you have G-suits?

There? I don’t think so. I have already forgotten. But it is a fact that based on the experience of the Americans, they later appeared.

I listened to the presentations of the pilots of Pepelyaev’s group, and one of them said, “The Americans had a special flight suit that helped them cope with gravity forces. In order to compensate for G-forces, we had to (he demonstrates) to align [our bodies] into a certain position to withstand the G-forces.

When G-forces are working on you, you can’t lift your arms or your legs. What alignment? I don’t understand it. Let’s not dwell on it. How can you overcome a G-load of four or six?

Six times your own weight—isn’t that a lot?

Perhaps it was even more. I did not have an instrument to measure the G-load. But to anticipate the force and to attempt to compensate for it? I don’t think so.

Were you able to see kills from the ground, how they fell?

I did not see any.

Did you ever see any captured Americans?

Americans, no. One time I did see some German prisoners. They led some prisoners through an airfield where we were stationed. Belorussian partisans were leading them. That was the only time.

What were your living conditions like? What did you do in your free time?

We had excellent living conditions. We lived in rooms, two or three men to a room.

Was some type of encampment built separately for you, close to the airfield?

No, who would do this? They were already there when we arrived. We fought at Andun in the period from February to May. [From February to 2 April 1951. I.S.]

Let’s go back to when you arrived in China.

We arrived there in July 1950, and left in October 1951. I participated in combat operations from February 1951. The regiment executed combat sorties from Mukden before my time. I only flew combat missions out of Andun.

What about your rations? Who were your cooks—our cooks, or Chinese?

I don’t know. But they fed us well. Perhaps it was our cooks. We had a norm for flight status and for instructors.

The rations were exclusively according to norm. But when we began to fly with the Chinese, some of them fainted from the G-forces. From hunger.

Ovsyannikov surrounded by Chinese cadets

Did this lead to crashes?

No, that didn’t happen. Only loss of consciousness. We began to investigate. They had their own cafeteria, and it turned out that they fed them a very sparse norm. The same as soldiers.

A bowl of rice.

A bowl of grass stems, not rice! Our command insisted that the Chinese begin to feed their men according to our norm. We did not hear about any fainting after that.

Pilots of the 28th Regiment observe the course of a soccer match between two Chinese teams in Leoyan, 1950

Did the Chinese and Koreans fought in the air during combat actions?

In addition to those whom we trained, there were none in combat. I did not see any. In our subsequent time in China we introduced several squadrons of Chinese pilots to battle. They were unsuccessful in their first aerial combats and suffered great losses. In the first battle they lost, I think, four or five pilots. They had no experience. Subsequently I do not know how they fought, and I will not speculate. We heard that they fought alongside Kozhedub’s division.

We know about three of our fallen pilots. Were there others?

Whom do you know about?

Vasiliy Fedorovich Bushemelev, Mikhail Petrovich Nosonov, and Sokov.

Volodya Sokov. I will answer this question. You are absolutely right. Nosonov died during a sortie from Mukden. They shot him up, wounded him in the neck. He landed at Andun airfield. He caught the aircraft shelter, and turned over. His aircraft nosed over and he died. This was a combat loss.

[Mikhail Petrovich Nasonov died on 11 November 1950 during a forced landing on Andun airfield, which was under construction. It is believed he landed in wounded condition, thus explaining his tragic end. I.S.]

Now Bushmelev and Sokov. By the way, Sokov was in my flight.

According to the records, the two of them collided.

I will tell you what really happened. We were on alert; my squadron was parked separately on one area on one side of the airfield. The other two squadrons were on the other side, near the headquarters. My squadron was farther away. We climbed down from our aircraft to take a break. We had an hour of readiness in the cockpit and than were allowed time for rest. At this time they sounded the alarm and launched aircraft. The telephone rang: “Prepare to launch! We are taking off for intercept; Shooting Stars are coming to attack Singisyu airfield.”

The town Singisyu was on the other side of the river; Korean pilots in Yak-9s were stationed at the airfield over there.

I sat in my cockpit, turned on everything, and waited for takeoff. But we did not take off. I saw a battle unfold over there, and somewhere at an altitude of about 2,000 meters, at a distance of, well, how many—10–15 kilometers—something like that, aircraft shining in the sun were visible.

This was around Andun?

Andun. We were parked at Andun. Nosonov died flying out of Mukden. This was now the second occasion. As we were watching, two aircraft collided. Bang! And the pieces flew everywhere. We thought it was two Shooting Stars.

When our aircraft returned, it turned out that this was two of our own pilots who, not seeing each other, were attacking one and the same enemy aircraft. They collided. [On 12 March 1951, Senior Lieutenant Vasiliy Fedorovich Bushmelev and Senior Liuetenant Vladimir Pavlovich Sokov collided in the air. I.S.]

Our regiment did not have any other pilot losses. Dubrovin was from another regiment.

Concerning the squadrons, how did you become a squadron commander? Whom did you replace?

I commanded, I think, the 1st Squadron. Whom did I replace? I think I came after Korobov, who moved up the chain of command. He became the deputy regiment commander, I believe.

[Initially Ovsyannikov was the deputy commander of Captain S. I. Korobov’s 3rd Squadron. In December 1950, Major Korobov became the deputy commander of 28th GIAP for operations, and Captain Ovsyannikov became the commander of 3rd Squadron. I.S.]

Did you ever have a feeling that we did not have enough strike aviation [in Korea]?

In what sense? What kind of strike? Bombers? I was not in command. Of course, the Americans had air superiority over Korean territory. They chased down every Korean vehicle in areas where we did not fly.

They wanted to plant us in Korea and build an airfield near Pyongyang, I think, somewhere around there. But as soon as a landing strip was built, an armada of B-29s would fly over at night and blow it away with bombs; they would make it useless.

What kind of aircraft did you see that the Koreans had? Il-2? Il-10? Tu-2?

They had various types. But I’m not sure what all they were. They were based on Korean territory.

Tell us, please, what did our MiGs look like?

Our MiGs looked good. They were silver. The air was painted, I think, all around. Ours [28th GvIAP] were white, and the 72nd’s were red. The recognition markings were Korean. We had a bort number as usual. My number? No, I don’t recall it.

Did they paint stars on them to acknowledge kills?

No.

What the composition of the squadron? Who arrived at the very beginning of the fighting? Who arrived later as replacements? Do you recall?

I had a replacement—Chernov. He was young. Bezmaternykh also was a replacement.

Whom did he replace?

Well, Gordeev, for example, left for reasons of health. He ejected when his aircraft was shot up. All who left us did so because of medical condition.

[The personnel roster of 3rd Squadron at the beginning of combat actions in Korean skies:

1. Korobov, Sergey Ivanovich – Captain, squadron commander;

2. Ovsyannikov, Porfiriy Borisovich – Senior Lieutenant, deputy squadron commander for flight operations;

3. Gordeev, Ivan Ivanovich – Captain, squadron zampolit;

4. Parfenov, Aleksandr Ivanovich – Senior Lieutenant, flight commander;

5. Pronin, Nikolay Grigorevich – Senior Lieutenant, senior pilot;

6. Motov, Nikolay Nikitovich – Senior Lieutenant, pilot;

7. Nekrasov, Nikolay Alekseevich – Senior Lieutenant, pilot;

8. Pokryshkin, Valentin Ivanovich – Senior Lieutenant, pilot;

9. Kuznetsov – Senior Lieutenant, pilot;

10. Anisimov, Viktor Vasilevich – Senior Lieutenant, senior pilot;

11. Krivulin, Aleksandr – Senior Lieutenant, pilot;

12. Bezmaternykh, Anatoliy – Senior Lieutenant, pilot.

Kuznetsov died in August 1950 of encephalitis; Korobov left for promotion; Gordeev, Nekrasov, Anisimov, and Krivulin went back to the Soviet Union ahead of schedule for reasons of illnesses and injuries or wounds. The following men arrived as replacements: V. F. Bushmelev and Viktor Grigorevich Monakhov (both from 72nd GvIAP), and also pilot Vitaliy Uryvskiy from the corps reserve. Bezmaternykh arrived from the regiment headquarters flight. I.S.]

Tell us, please, how did the political officers keep busy?

I don’t know. The squadron zampolit flew. But they still conducted meetings, and so on. They did what they were supposed to do.

The last time, you became quite indignant when we raised the issue of Smersh personnel. What is your perspective on Smersh?

I think this was an enormous effort devoted to the uncovering of enemy agent networks. I think that without them… well, I don’t know how to explain it to you. Who would do what they did?

Now there are many arguments about this, and we are openly asking you.

Arguments… right! Of course, they were necessary.

Now all of our films show that these “sons of bitches” and so on only thought about how and whom to cram into a penal battalion. On the other side was the good film, In August ’44.

What film? I haven’t watched any films lately. Anyway, in these films the Smersh officers are cursing, the types of faces they select for these roles! In our regiment we had a lieutenant, a modest guy; I have even forgotten his name. He had his own separate office, where he did his business. He was invisible to us, but his work was necessary.

Are there cases in your memory when a non-flying Smersh or political officer asked you to teach them how to fly?

We did not have any such cases. The Smersh men in general did not fly. I don’t know. The zampolits in the regiment, before they became political officers (in higher units), all flew, and later became “no-flying.” They did not fly after the war as well.

Returning to Korea, where and when did you fly your first sortie in Korea? How did it go?

How would I know?

Well, did you see the enemy?

I don’t remember. Gentlemen… how may years have passed? [It is likely that Ovsyannikov made his first sortie in February 1951, somewhere after the 10th, and had his first combat engagement on the 14th of February. I.S.]

With whom were you most often paired?

I flew in pair with my deputy, with Pronin.

The zampolit?

Yes. He was an outstanding wingman. With him, together we could fight effectively with the Sabers.

Did many men come down with fear-induced diarrhea?

It happened, it happened. You don’t know for sure, but…

Of the two regiments at our base, one regiment was formed. Monakhov came to our squadron from the 72nd GvIAP. As I now recall, he had a red intake on his aircraft.

We were in a dogfight with some Sabers; there was such a commotion and such G-forces. I was thinking to myself, “I’m alone.” Then I glanced around, and he was behind me. He was a remarkable pilot, if you please – the best of all my wingmen.

[A portion of the 72nd GvIAP was engaged in the training of Chinese pilots at Anshan, and did not participate in the February battles. However, when the pilots of the 28th GvIAP got in a bind, reinforcements began arriving in March from the 2nd Squadron, 72nd GvIAP of Major Bordun. Later another squadron of this regiment was sent to Andun. I.S.]

How would you grade your zampolit as a wingman? As a pilot?

Not bad. By the way, he brought my aircraft into his sight when he was attacking a bomber. It showed on the gun-camera film. It was very close. A casing from one of my rounds was stuck in his stabilizer. I was in his sight, he had one hole from a bullet from the bomber’s gunner and a hole in the stabilizer—this long, 10 centimeters. We landed. What was this? Did the Americans have a new weapon? We began to speculate. Later when they picked through the stabilizer, they pulled out my 37mm casing. When I fired, he was so close to me that it hit him in the butt end of the stabilizer. By the way, he was an aircraft technician during the Great Patriotic War, and transitioned to be a pilot. [Pronin was shot down in combat on 25 February 1951. I.S.]

How do you rate the rifled armaments of the B-29 bomber?

I would say they were very good. By the way, when they fired at us, they smoked, and you think, is the bomber burning, or is it machine gun smoke? That’s how it was.

At what distance did you open fire?

For me it was 600 meters. I did not even manage to pull away before I found myself between the wings of [adjacent] aircraft.

What about with fighters, with all their differences? Did you normally fire from the same distance?

Normally somewhere from 600 to 400 meters. They did not allow you to get any closer. The Saber could pull away from us in a dive. In a dive, it was the same as a Focke-Wulf 190 from a Cobra. We could not catch them in a dive.

In your opinion, what was the better airplane — the MiG or the Saber?

For me it was the MiG.

In what way was it superior to the Saber?

I don’t know. But I fought with them. And I got out of difficult situations. Does this mean anything? Either I was better, or the other pilot was not as good, or…

Well, how did you get out of it? Did you always use the same methods, or various methods?

I got out, as a rule, by climbing. We did not engage in pure turns. They taught us that in the regiment. In the first place, it’s difficult to hit someone while turning because it’s hard to stay on his tail. The bullets fly behind him.

Did you deploy your air brakes in combat?

I did not.

What kind of actions did you have to undertake in order to deploy your air brakes? Did you have to take your hand off the throttle?

No. You pressed a button on the stick [to deploy them], and when you released the button they retracted. The cannon button was on top, under your thumb. The machine gun triggers were on the front. But we reconfigured them under a single button. It was the same on the MiG as it was on the Cobra. You press on one trigger and everything fired.

The Airacobra was modified in many Soviet regiments to permit the firing of the nose-mounted 37mm cannon and two .50 caliber machine guns with a single trigger. [JG]

Did you have adequate ammunition in the MiG for combat?

Of course, we had enough. You asked if we could shoot down two aircraft. I don’t know; perhaps not. In the MiG we had enough for battle, for one engagement. But you did not want to go “dry.” They advised us not to fly “dry,” without ammunition. You never knew if you might not need it at any moment before landing.

Did you have an ammunition counter? Something that kept track of your shells?

No. The MiG was like the Cobra — not a large reserve. In my opinion, also 30–40 rounds. This was for the 37mm cannon. I think we had 120 for the 23mm cannons.

They taught us to economize and not fire up our ammunition supply totally. They trained this even in the Great Patriotic War. When you are arriving at your airfield, “keep your ears open.” Because you need to hold back some ammunition in combat in the event someone attacks you while you are landing.

Wasn’t there an order in the Great Patriotic War that you were to expend all your ammunition on the enemy?

No. They even cussed us out if we did. They used this short verse to teach us:

Don’t expend shells for nothing!

Get as close to the enemy as possible,

Press on the trigger

When the enemy fills half of your sight!

“Fills half of your sight” is about 200 meters or less.

What kind of coordination occurred between you and those who came to replace you? Did you prepare them? What did you explain to whom?

Yes. There was some type of hand-off, but in very brief form. I think even Pepelyaev was with me. Pepelyaev came to the position of the regiment commander, it seems, from the position of division inspector. I conducted a preliminary “ briefing of the pilots,” and there was an inspector from division, a major. I don’t recall his last name.

Did you leave Korea as a squadron commander?

Yes. My subsequent position was regiment commander.

In your opinion, was the unit that replaced yours a worthy one?

How did I rate it? First, the division that replaced us was commanded by Three Times Hero of the Soviet Union, the famous pilot of the Great Patriotic War, Ivan Kozhedub.

I have heard a lot about him, that he was called “Vanya-dub”? [Pilots thought Kozhedub to be as tough and stubborn as an oak tree. Ed.]

I don’t know. I do know that he was from our Chuguev flight school. He was an instructor. I learned from an order that on one occasion he flew with a female parachutist and during landing he damaged the aircraft. Well, so what! Later he became a Three-Times Hero!

You have, let us say, more than a few kills.

I will tell you honestly, as Melekhin, the regiment commander, taught me: “Accomplish your mission! If you are the wingman, you are responsible for the leader. It is not your job to get kills! Moreover, if you are escorting other aircraft, it is not your job to shoot down enemy aircraft; you are to protect the bombers! This is what they taught us. You fend off the attack! Beat them off, so they don’t shoot you down. Keep your place where you belong!”

He pounded this into me. My kills… they are a byproduct. During the Great Patriotic War, I had two Fokkers, and in Korea, four: B-29, a Saber, and two “Crosses” [Thunderchief]. Not much, but they are all mine! Of course, I was not able to confirm every kill. It seems to me I shot down one B-29, one Saber, and two “Crosses.”

[Regarding the victories of Porfiriy Borisovich Ovsyannikov: His official score for the Korean War is listed as seven victories, but a portion of them are indicated in the records as “probables.” (Not confirmed later).

Ovsyannikov’s first victory was recorded on 14 February, a B-29. However it is more likely that he (like other pilots at that time who claimed victories over B-29s), in the best case, only damaged several B-29s, which all returned to their bases and all were repaired. The Americans did not report any losses or damaged B-29 aircraft overall on this and the subsequent two or three days.

According to our augmented data, of the four claimed B-29 victories on this day, only one B-29 struck the ground, and more than likely it fell either in the sea or on South Korean territory. Therefore, the Americans did not report this loss. It is more likely that the regiment commander, Kolyadin (he fired from very close range) scored this single B-29 on this day; the rest of the pilots (including Ovsyannikov) fired at the B-29s from ranges of 1,000 meters and greater. Of course, in the best of circumstances they could only have lightly damaged an additional one or two B-29s, but certainly not down them, although victories were credited to all four. Thus it can be said with certainty that Ovsyannikov’s first victory did not occur, in light of the absence of experience of combat with such aircraft as the B-29.

His second victory was on the 23rd (!) of February 1951 (Red Army Day) over an F-80, confirmed by the American side. In this engagement Ovsyannikov seriously damaged one F-80. This was F-80 No. 49-1860 from the 8th Fighter Bomber Wing. Though it flew back to its base, it was destroyed during landing. Naturally, the Americans recorded this loss as “non-battle,” the aircraft ostensibly having been destroyed “for technical reasons.” In fact, it landed in damaged condition and during the landing suffered a catastrophic accident.

Ovsyannikov’s third victory was again a B-29, on the 25th of February. On this occasion, the errors committed in the previous battle with B-29s (14 February) were taken into account, and four B-29s were shot down. All of them were credited to the personal scores of our pilots as confirmed. The Americans acknowledged these losses, but only five days later. They acknowledged the loss of three B-29s and an additional damaged B-29. One B-29 went down on North Korean territory and crashed there, and an additional two flew back to their bases and landed. Because of the heavy damage they received, both were consigned to scrap. Only one of the damaged B-29s that returned to its base on this day was repaired. All three lost B-29s were from the 98th Bomb Wing of the USAF. Thus Ovsyannikov’s victory on this day was confirmed!

In the next engagement with B-29s on 1 March, our pilots claimed that they damaged (note—not shot down, but damaged) 10 B-29 aircraft. But according to photographic data, three confirmed B-29 victories were credited, two of which the Americans acknowledged: one B-29 was destroyed during landing in South Korea, and another was written off because of the heavy damage it received. The remainder were repaired. These again were B-29s from the 98th Bomb Wing, and it is most likely that B-29 No. 44-69977, which was destroyed in South Korea, was the work of Ovsyannikov (shot from close range). This victory can be credited to Ovsyannikov.

Ovsyannikov’s next victory is dated 2 March and is recorded as his first F-84. In fact in this engagement a group of MiGs of the 28th GIAP fought with a group of F-80s and F-84s. Initially our pilots were credited with three F-84s, but latter the record was corrected to two F-80 kills and one F-84 kill. Ovsyannikov shot down one F-80 in this engagement. The Americans confirm the loss of two F-80s from the 25th Squadron, 51st Fighter Bomber Wing, but three days later and because of damage received “from antiaircraft fire.” In fact, they were damaged by the fire of MiG cannons and thought they made it to their base in South Korea, both aircraft were written off as unrepairable. Thus this victory of Ovsyannikov also has confirmation.

Ovsyannikov gained his last two victories on 30 March—a B-29 and an F-86. The Americans confirm the loss of a B-29. This bomber crew was from the 28th Squadron, commanded by Captain Gallaher. He managed to limp his damaged B-29 No. 44-69746 to the base at Itazuki in Japan, but the aircraft was so damaged that it was consigned to scrap. Ovsyannikov’s second victory in this same engagement was not an F-86, but an F-80 from the 9th Squadron, 49th Fighter Bomber Wing. Its pilot went missing in action on this day, and it was mistakenly recorded as an F-86.

In the final tally, of Major Ovsyannikov’s seven claimed victories, six can be confirmed: three B-29s and three F-80s. If one speaks of confirmation from our side, then all claims of victories are based principally on statements of our pilots. In this period, the front in North Korea was not stable and a portion of the territory of the KNDR was still occupied by UN forces. Therefore our pilots were forbidden from flying deep over the territory of North Korea. Naturally, it was dangerous to send out search parties into the front-line zone and this was not done.

All victories were counted in this period exclusively based on photographic evidence and the observations of Chinese and North Korean ground forces, or on data from radio intercepts. As the above discussion makes clear, our claims in large part corresponded to reality and had confirmation from the American side, though to this day they have tried to hid their losses in battles with MiGs under various pretenses, such as: “equipment failure,” “ground fire,” “insufficient fuel,” “accident upon landing,” and so on. As a matter of fact, in this period the Chinese and North Koreans had so few antiaircraft units ( (our antiaircraft resources had not been deployed yet) Korean AAA artillery at the described time consisted of mostly 85mm guns, mostly located around Phenyan, and 12,7 DShK portable machine guns, also in a very low quantities. AA became a real threat for UN aircraft no sooner then 1952.) that it is laughable to read the American claims of losses of their aircraft, the more so jet-powered aircraft, “from antiaircraft fire.” I.S.]

Many years have passed. What is your attitude toward the enemy—toward German pilots, toward the Americans? If you were to meet them now, what would you say to them?

The pilots themselves are blameless. Those who sat in positions of authority are guilty. We both have a similar love for the air.

So in principle, upon meeting them, you could shake hands?

Why not? We fought. We are equals. Well, perhaps I would not be able; I refused to see an American who wanted to talk to me about Korea. Well, I could not do that. Even now I consider Americans my enemies. Oh, well!

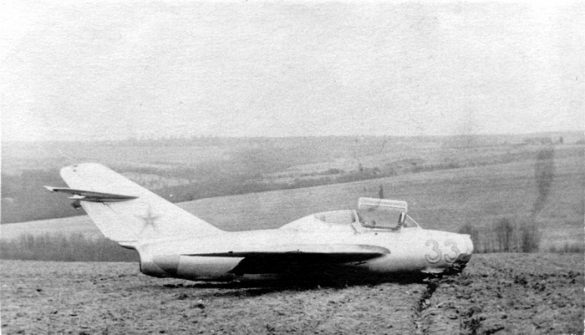

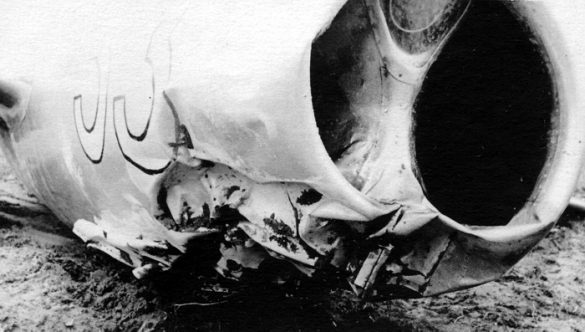

Even in peacetime, the aviation profession is dangerous. In my 33 years of flying duty, I had to execute a forced landing five times because of engine failures. Of these, on three occasions it was off the airfield, on my “belly,” with retracted landing gear. One of these belly landings was photographed. It was on 29 October 1956, when I was conducting a weather reconnaissance in a two-seat MiG-15 on the last flying day before my leave.

My fate decided

That I would live;

All the bullets passed me by.

It found level fields for me,

Where I could land,

Saving my life and the aircraft

In order to fly again,

With my hand at full throttle.

What did you fly after Korea?

In the MiG-17, then the MiG-17PF. But the MiG-15 was more maneuverable. The MiG-17 was less responsive. The same with the engine. The speed brakes—these were the same type of air brakes that the Saber had, but not quite as large.

The MiG-19, in comparison with the MiG-15—I don’t know—an oak [unresponsive Ed].

Enough of all of that. I want to confirm the opinion that exists among aviators that those who have associated themselves with the profession of pilot — and it’s not important if they are military or civilian — for their entire lives are afflicted with an incurable illness: nostalgia for the limitless expanses of the aerial ocean. It seems to me that fighter pilots suffer from this illness most of all. I have suffered from this illness for more than 30 years, and one time expressed my dream in verse:

Dream of a Former Pilot

It seems that not long ago I was in a MiG-15;

I plowed the expanses of the blue skies,

Already 30 years have flown by

Since the last time I held the stick in my hands.

In combat in MiGs in Korea we did not screw up,

And now in our old age we remember;

How in the skies we crushed “fortresses” [B-29s] there,

And their wreckage was falling down to burn up on the earth.

And how the Sabres scattered from our salvoes,

When we came up behind them in air battles…

How we frequently sortied on alert,

To cover the dam and Andun bridge.

Many years have passed, and my days of flying are gone.

It seems I can’t resign myself to this fate.

Still, even if just once, to climb upward in a MiG

And execute a cascade of aerobatic maneuvers.

Climbs so steep my eyes would grow dark,

Turn, loop, then an Immelman,

Where the G-forces press my body into the seat,

So that a thick fog comes over my eyes.

To complete the Immelman in a snap roll

And again streak down from great height,

With a combat turn to place points in the sky

And in this way spend the entire night: dream, dream, dream…

Now both the MiGs and I have grown old,

Missile-laden systems have come to replace us.

Its metal has become brittle and my eyes have grown weak…

But just the same, I’d love to go back to the old days one more time.

Footnotes

1. This was a jeep-like vehicle, named from its factory of production—Gorkiy avtomobilnyy zavod. [JG]

2. The Airacobra was modified in many Soviet regiments to permit the firing of the nose-mounted 37mm cannon and two .50 caliber machine guns with a single trigger. [JG]

By Oleg Korytov and Konstantin Chirkin ©

Transcribed by Igor Zhidov ©

Translated by James F. Gebhardt © and edited by Ilya Grinberg ©

Special thanks to Svetlana Spiridonova, Mikhail Bykov, and Igor Seidov (whose commentary is annotated “I.S.”)