Based on presentation at the International Scientific and Practical Conference, “The World War II Results and the Mission of Securing Peace in the XXI Century”, St. Petersburg, House of Friendship and Peace, April 27–28, 2000, with additions, corrections, and illustrations.

The events of WWII in the Northern Pacific by far remain largely unknown. This said, the data from the President’s Reports to Congress on the Lend-Lease Operations (1) clearly show that nearly half of the goods destined for the Soviet Union were shipped via the Pacific Ocean. The goods were directed across the Pacific Ocean to Soviet Far Eastern ports, and through the Bering Strait via the Northern Sea Route (1*). The shipments began as early as June 1941 (2, 3). Starting in December 1941, until the capitulation of Japan, they were carried out in the zone of the military operations.

With regard to naval and military activity in the Northern Pacific, a single source of comprehensive and reliable information simply does not exist. There are multiple accounts of the Japanese occupation of the Aleutian Islands of Attu and Kiska and the subsequent combined U.S. – Canadian campaign against the Japanese forces. Another well-known episode is the Battle of the Komandorski Islands in March 1943 (4). Other sources describe the raids by American bombers from the Aleutian Islands against Japanese fortifications on the Northern Kurile Islands, and from western China against the targets in Japan and Manchuria (5).

The obscurity is evident even in the President’s Reports to Congress (1), which declared no losses on Pacific routes, including the Siberian leg of ALSIB (Alaska to Siberia route for ferrying aircraft to the USSR). Such statistics are extremely difficult to believe. The only reasonable explanation is that the Soviet side simply refused to inform their allies about such losses. At that time, the GULag NKVD (The Chief Administration of the Camps of the People’s Commissariat of Internal Affairs) largely controlled Siberia, and any American attempt to visit the Soviet Far East would be highly undesirable for Soviet officials.

The wartime history of the entire Soviet Far East, as well as the history of the Soviet Pacific Transport Fleet operations, was placed off limits by the NKVD. Any information on the subject remained inaccessible, and thereby repressed for over half a century.

Altogether, the Allies sent almost 18 million tons of all sorts of aid to the Soviet Union using various sea routes (*2). Over a half of this cargo arrived via the Pacific Ocean. Pacific routes were generally safer than the Atlantic ones. About 500,000 tons were lost in the Atlantic, while the losses on the Pacific routes were one-tenth that large (2, 3). The military and strategic resource aid to the Soviet Union came mainly from the United States. The Lend- Lease Program was commenced on 1 October 1941, but some goods had been moved prior to that date under a “cash and carry” agreement.

Lend –Lease was a form of military assistance of the United States to its Allies in forming and fighting anti-Hitler coalition. It was the currency-free mutual exchange of goods and services where the payments would be postponed until after the war, and completed in installments over many years. Anything lost in battle or during the delivery was to be excluded from the calculations.

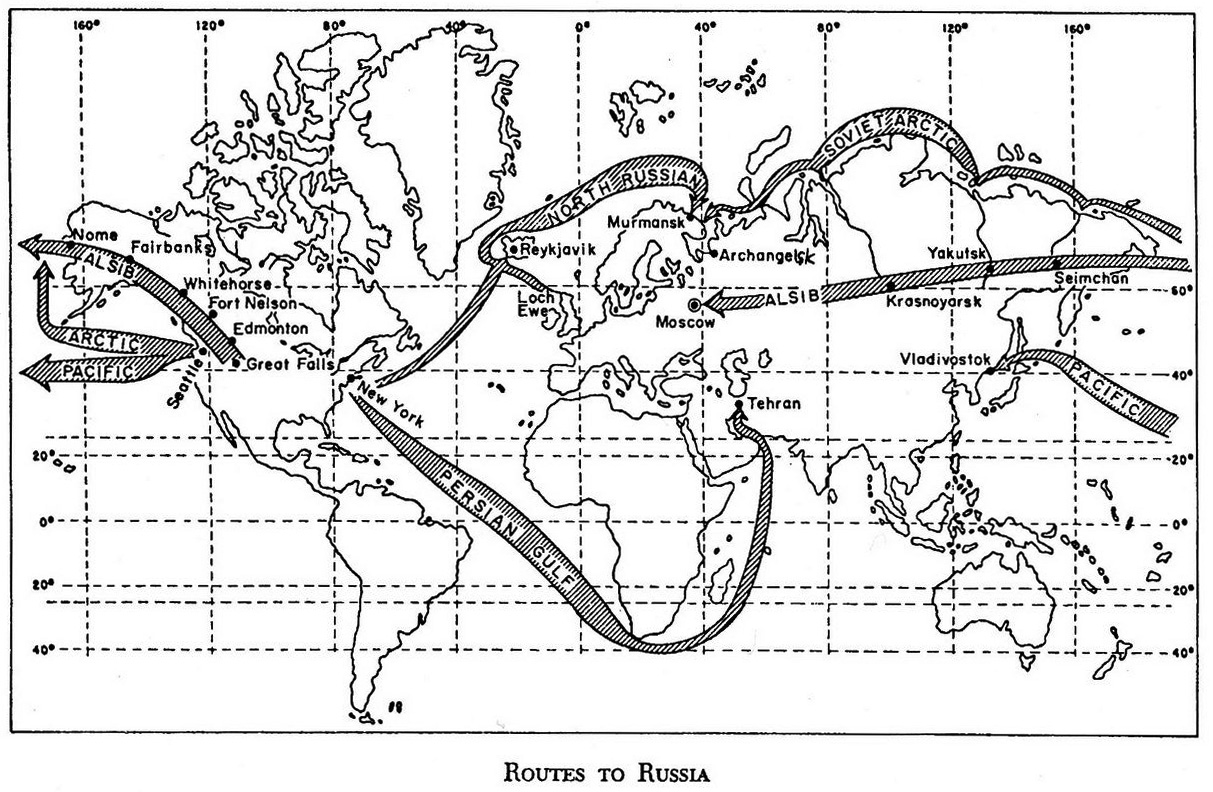

Following map by Robert H. Jones (2) depicts the distribution of the aid for the USSR among different routes:

Route / Volume, long tons*

North Russian 3,964,000

Persian Gulf 4,160,000

Black Sea** 681,000

Soviet Far East (Pacific) 8,244,000

Soviet Arctic 452,000

*Long ton is equal to 2,240 pounds or 1,016 kg

** The author’s remark: the route via Mediterranean and Black Sea opened up after the end of the hostilities in Europe in May 1945, and had been functioning until September 20, 1945

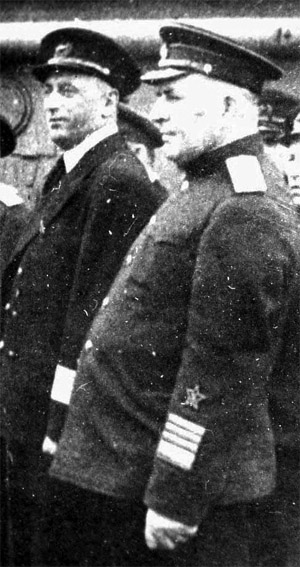

Alexander Afanasiev, the head of Far Eastern State Shipping Company at the beginning of the war (left), and Admiral Ivan Yumashev, Commander of Soviet Pacific Fleet

The most important men of the sea at the Soviet Far East: Alexander Afanasiev, the head of Far Eastern State Shipping Company at the beginning of the war (left), and Admiral Ivan Yumashev, Commander of Soviet Pacific Fleet. As of 1942, A. Afanasiev became a Deputy of the People’s Comissar of the Soviet Merchant Fleet and Authorized Representative of the State Defense Committee which entitled him to supervise the Soviet sea transportation in its entirety. After the war Alexander Afanasiev became a Minister of the Soviet Merchant Fleet, and Admiral I. Yumashev became the Commander-in-Chief of the Soviet Naval Forces. Photo from the author’s archive.

The Carriers of the Pacific Route

A good deal of controversy exists on the subject of who exactly performed the task of transporting the aid across the Pacific Ocean.

Michael N. Suprun, Professor of the Department of Native History of Pomorsky University in Archangelsk, states that the Americans carried out the delivery of the USSR-bound cargo to Soviet Far Eastern ports prior to the Pearl Harbor attack (6).

Richard J. Overy, professor of the New History of the London King’s College (*3), writes that after December 1941, almost all the shipments in the Pacific Ocean were carried out by the United States (7).

The truth of the matter is that only vessels under Soviet flag, manned by Soviet crews, carried out the entire USSR-bound Pacific shipping. Just as it was stated in the Report of the People’s Commissariat of External Trade: “Soviet steamers, exclusively” (8). There were no convoys. The vessels sailed across the ocean one by one without any escort, although many historians and officials still write about “Pacific convoys” in their publications.

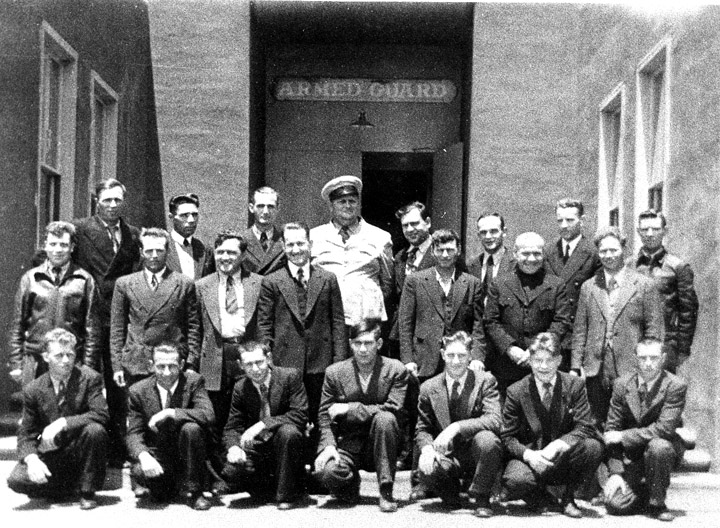

Just as it was the case with the Atlantic cargo vessels, the ships had protective armament and military squads aboard. Many Soviet merchant sailors obtained military professions in Armed Guard Center of San-Francisco.

A group of Soviet merchant sailors after completion of gunnery course at the Armed Guard Center of San Francisco. Photo from the author’s archive.

By November 1942, the Allies had officially refused the old and slow-going Soviet vessels to participate in Atlantic convoys. By then, the USA, Great Britain and Canada had established mass production of welded, heavy tonnage dry-cargo ships and tankers. From December 1942 onward, the Atlantic convoys were formed from those newly built ships. The inbound convoys now re-abbreviated “JW” from the previous “PQ”, operated during the polar nights only. As a result, the losses on the sea routes to Murmansk and Arkhangelsk had decreased considerably (15).

By the beginning of 1943, those Soviet merchant vessels that had not been destroyed or mobilized to the Soviet Navy, as well as those excluded from JW convoys, were transferred to the Far Eastern State Shipping Company (FESCO). In June 1941 there were total of 85 vessels in the FESCO fleet. During 1941–45, 39 more vessels were transferred to FESCO from other Soviet steamship companies. Lend-leased American ships began joining FESCO fleet beginning in 1942. At first, they were old American vessels, repaired under the auspices of the so-called Special Program. Beginning in January 1943, the Soviet Government Purchasing Commission in the USA started to receive brand-new heavy tonnage dry-cargo ships of the Liberty class and tankers. Altogether, 128 vessels were received in different U.S. ports under Lend-Lease Law (9).

Year /Number of ships received

1942 27

1943 46

1944 20

1945 35

“Krasnogvardeets” was the first “Liberty”- class freighter, purchased for FESCO. Pictured in the vicinity of Seattle by the U. S. Navy patrol plane. The wartime livery includes Red Soviet flag and Black letters “USSR” on White. At night these signs were lit with bright lamps, suspended from the sides. The vessel is flying identification signals “UOJC” in lieu of the name, which was painted over. Bow and stern guns are clearly visible. (via Boris Ilchenko)

Alexey Yaskevich, the first captain of “Krasnogvardeets”, photo from the author’s archive.

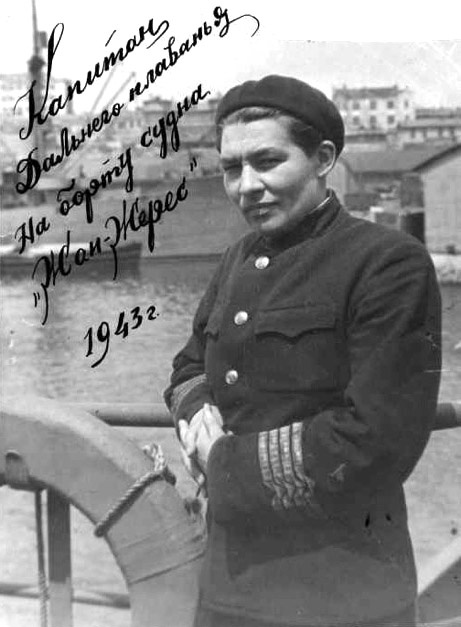

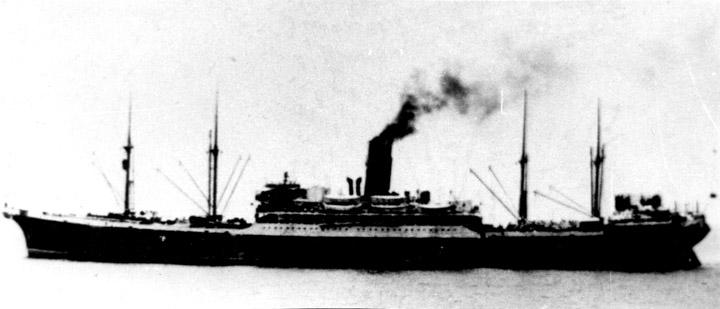

“Jean Jaurиs”, the second “Liberty”- class freighter, purchased for FESCO

and its captain Anna Shchetinina, photos from the author’s archive.

The fleet of Dalstroy NKVD (Far Eastern Gold Mining Company of the People’s Commissariat of Internal Affairs) also participated in cargo transportation across the Pacific Ocean. This fleet consisted of four heavy tonnages, high-speed vessels. They worked on the America – Vladivostok line throughout the war, and alone hauled close to 500,000 tons of cargo (10).

Flagship “Felix Dzerzhinsky”, photo from the author’s archive.

Steamer “Dalstroy” in wartime livery, photo from the author’s archive.

In accordance with the Lend-Lease Agreement, American and Canadian shipyards performed repair work on the Soviet vessels. Some 30 Soviet fishing and factory ships of People’s Commissariat of Fishing Industry were repaired under this program, and always returned home with Lend-Lease cargo aboard. Outside the fishing season, transport ships of fishing companies continued to function as cargo carriers. In addition, two refrigerated vessels of Vostokrybkholodflot (East Fishery Refrigerated Fleet) and a tanker of AKO Fleet (Kamchatka Joint-Stock Company) worked on the America – Vladivostok route continuously.

Factory Ship “Pischevaya Industriya”, photo from the author’s archive.

Freighter “Yakut” of AKO Fleet made three round trips across the Pacific Ocean during the war, photo from the author’s archive.

According to the data of the President’s Reports, the amount of cargo loaded onto Soviet vessels for crossing the Pacific Ocean during the war was 124 times the amount sent with the Soviet ships via Atlantic routes. Without much of exaggeration, this extraordinary effort could rightfully be called the Pacific Transport Йpopйe*.

*Йpopйe (French, from Greek εποποιία): a series of grand scale events, usually- military deeds, as well as literature, describing it.

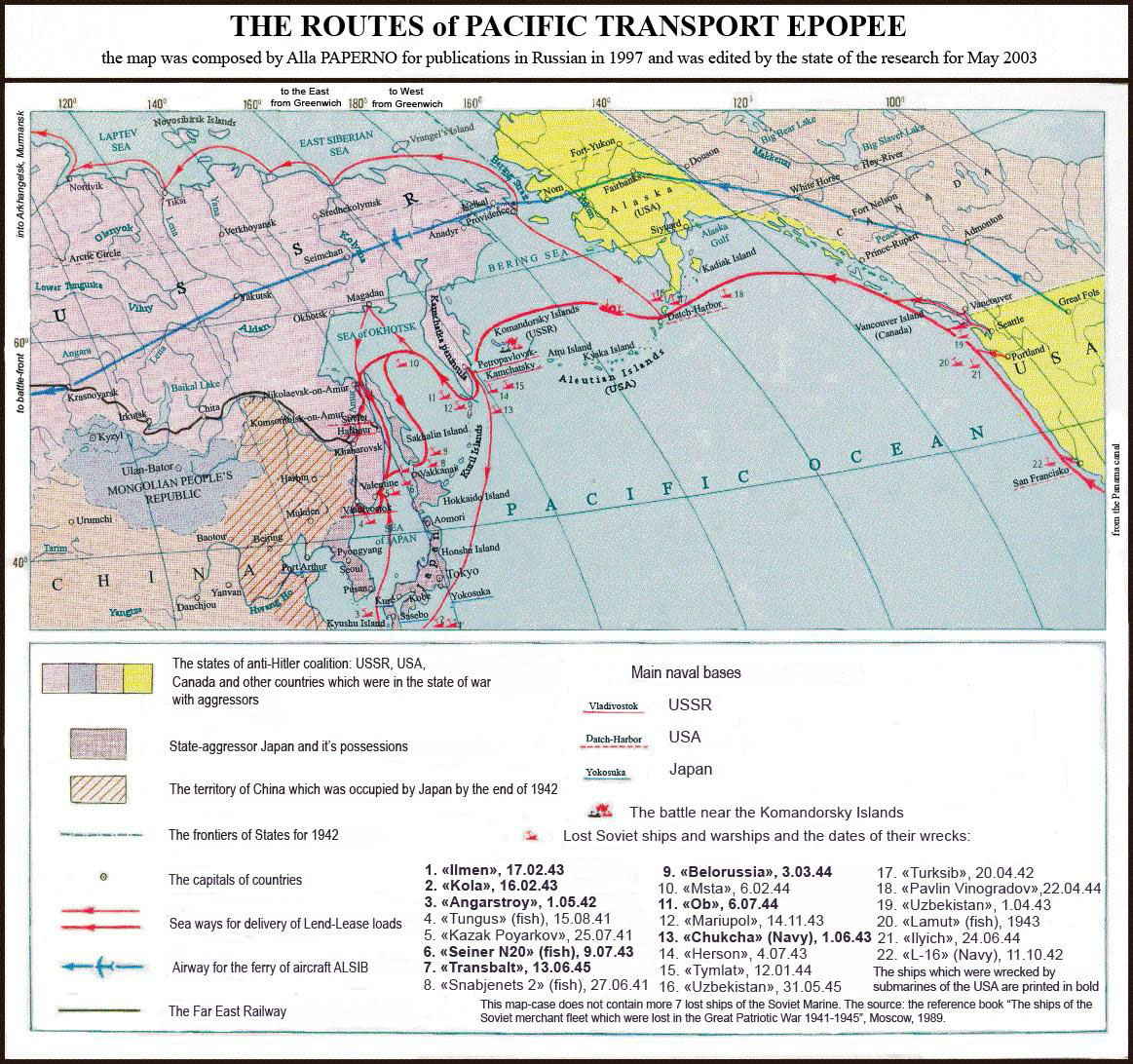

The following map “The Routes of Pacific Transport Йpopйe” («Маршруты Тихоокеанской транспортной эпопеи»), was published in my book «Lend-Lease. Pacific Ocean» (Moscow. 1998, p. 18) and in the Historical and Geographical Atlas «Kamchatka XVII—XX Centuries» (Moscow. 1997, p. 94). It was updated in accordance with new research discoveries in 2003.

The Routes of Pacific Transport Йpopйe

Lend-Lease cargo arrived to the Soviet Far East from numerous ports of the West Coast of the USA and Canada, as well as from the East Coast of the USA via the Panama Canal. The ships steamed north along the American West Coast, and then continued on westward toward the Aleutian chain. Near Unalaska Island, regardless of the season, they passed into the Bering Sea.

During the summer navigational season, a portion of the vessels sailed north from Unalaska to Providence Bay, the harbor on the southern coast of Chukchi Peninsula. This was the gathering point for Northern Sea Route caravans. Only ice navigation-proficient pilots could lead those caravans. They steamed via the Bering Strait into the Arctic Ocean. In the mouths of large Siberian rivers, the cargo was transferred onto river vessels and barges. This was the principal supply route for the Alaska-Siberian aircraft ferrying route. Therefore, ALSIB itself was a part of the Pacific Transport Йpopйe.

The majority of the vessels steamed west from Unalaska, then went around the Komandorski Islands, and continued south along the Kamchatka coast. Vladivostok was the principal port of destination due to the convenience of the Trans-Siberian Railway.

In the wintertime, traffic across the Sea of Okhotsk and La Perouse Strait to Vladivostok was halted by difficult ice conditions.

The Japanese closed the unfrozen Tsugaru Strait to Soviet navigation, although Japan and the USSR were not at war until August of 1945. The route around the Japanese Islands through the Korea (Tsushima) Strait took much longer and was more dangerous. In the winter the ships were fully unloaded in the port of Petropavlovsk-Kamchatsky, and returned to the U.S. ports for another load of cargo.

The Japanese Navy and Coast Guard inspected Soviet ships passing via La Perouse Strait. Only non-military cargo could be transported on that route. In the summertime the vessels with military and strategical cargo had to be partially unloaded in Petropavlovsk to reduce draft, and continued on across the Sea of Okhotsk, through the shallow waters of Amur Liman (*4) into the Strait of Tatary toward Vladivostok.

The cargo ships also entered the port of Petropavlovsk to coal, fuel, and replenish stocks of fresh water on board. They were often called in to await the resolution of frequent traffic congestion in the port of Vladivostok, especially during the first months of the war.

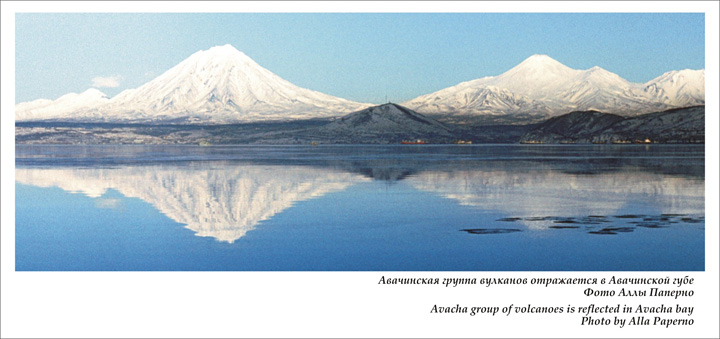

Port of Petropavlovsk-Kamchatsky. Koryaksky and Avachinsky volcanoes dominate the background, and reflect in the waters of Avacha Bay (Avachinskaya Guba) (photo by Alla Paperno).

Sea approaches to Petropavlovsk, Vladivostok and other Far East ports during the war were protected by minefields. Naval pilots navigated ships into the ports. In Kamchatka their station was located in Akhomten Bay, south of Petropavlovsk. (It is known today as Russian Bay). There, caravans of 3–5 vessels were assembled, and a naval pilot led them through the passages in the minefields to Avacha Bay. The station of the convoy officer was also located in Akhomten Bay. His function was to instruct the captains of the vessels on the route to their destination.

Freighters steamed around Cape Lopatka, then turned north along the western coast of Kamchatka. Vessels bound for Magadan continued from there to the port of Nagaevo. The remaining ships changed their course at the directed point in the northern waters of the Sea of Okhotsk. Vessels with military and strategic cargo aboard went along the Amur Estuary into the Strait of Tatary. General cargo freighters sailed via La Perouse Strait. From La Perouse, Tatary and Korea Straits, they proceeded to the Bay of Valentine. From there naval pilots took the lead of the 3–5-vessel caravans through the protective minefields to Vladivostok.

The cargo that was unloaded in Petropavlovsk and Magadan made its way to Vladivostok during the summer by the ships of Nikolaevsk-on-Amur Steamship Company, which operated only inshore navigation vessels.

Smaller number of freighters, arriving from the USA, unloaded their cargo onto river vessels and barges in the port of Nikolaevsk-on-Amur. Then the goods were delivered upstream on the Amur River to Komsomolsk and Khabarovsk. The construction of the railway from Komsomolsk to Sovetskaya Gavan (Soviet Harbor) was initiated during the war.

The Volumes of Transportation

During WWII, the port of Vladivostok turned over more than 10 million tons of cargo, 79 percent of it imported. The port processed 32,000 freighters; it loaded and sent on the Trans-Siberian Railway almost 400,000 railroad cars (covered and flatbeds). In comparison, during the same time period, the port of Murmansk handled just over 2 million tons of imported goods (11). The Arkhangelsk group of ports (5*) processed another 1.7 million tons (2, 11).

At the beginning of the war, the port of Petropavlovsk-Kamchatsky had a single wooden non-mechanized berth. Nevertheless, it processed the bulk of over 2 million tons of imported cargo, according to data from the State Archives of Kamchatka Region. To achieve such a result, a modern merchant seaport was built in Petropavlovsk-Kamchatsky during the war. It had the capacity of one million tons of freight per year with six mechanized berths. The construction took just over two years to complete.

A multitude of other Far Eastern ports, railways, airfields and roads were built or remodeled during the war.

Vladivostok and the Far Eastern Railway transported four times the amount of cargo of Murmansk and Kirovsk Railway, and five times of the Arkhangelsk group of ports and Northern Railway.

Losses of the Soviet Cargo Fleet

Many historians are contented with the notion that the North Pacific routes were very safe. But does this correspond with the facts?

During 1941–44, the Japanese Navy and Coast Guard stopped and detained Soviet transport ships 178 times for periods from several hours to several months (9, p. 197). Submarines of the combatant states patrolled the area. The great sea battle of Komandorsky Islands took place near the routes of Soviet vessels. A total of 23 Soviet ships were lost in the Pacific Ocean. Of those, nine were stranded on the rocks by storms, crushed by ice floes or blown in Soviet minefields. The remaining 14 were destroyed either by enemy action or friendly fire.

In December 1941, the Soviet freighters Krechet, Svirstroy, Sergei Lazo and Simferopol were undergoing repairs in the port of Hong Kong, when the Japanese captured the city. The vessels were destroyed by Japanese artillery.

In the same month of December 1941, the freighter Perekop and the tanker Maikop were sunk by Japanese aviation in the South China Sea and near the Philippine Islands, respectively.

Maikop (via Boris Ilchenko)

The Japanese submarine I-162 torpedoed the freighter Mikoyan, which sank on 3 October 1942 in the Bay of Bengal.

Many years later, after the end of WWII, it became clear that U.S. submarines sank six Soviet freighters and one fishing vessel near Japanese shores. The U.S. submariners’ battle slogan was: “Sink ‘em all!” They had sunk a lot of their own cargo ships in the southern Pacific zone of war operations. As a rule, Soviet vessels underwent American torpedo attacks in bad visibility conditions: in fog or at night.

Following is the list of the Soviet vessels that were lost to American submarines:

Angarstroy — May 1, 1942, East China Sea, to the U.S. submarine SS-210 Grenadier

Kola, Ilmen — February 16 and 17, 1943, Pacific Ocean, SS-276 Sawfish

Seiner #20 — July 9, 1943, Sea of Japan, SS-178 Permit

Belorussia — March 3, 1944, Sea of Okhotsk, SS-381 Sand Lance

Ob— July 6, 1944, Sea of Okhotsk, SS-281 Sunfish

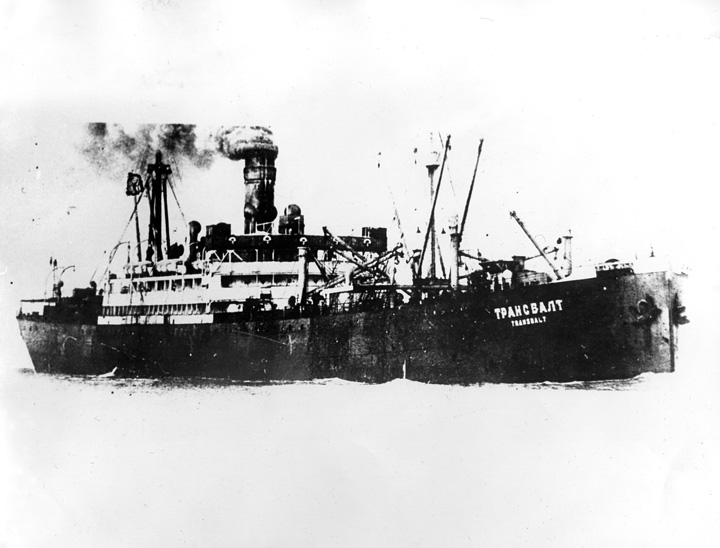

Transbalt— June 13, 1945, Sea of Japan, SS-411 Spadefish

“Transbalt”, photo from the author’s archive.

Memorial to the lost ships of Soviet Merchant Fleet, Vladivostok. “Transbalt” plate (photo by Alla Paperno).

According to the reference book of the USSR Merchant Fleet Ministry (12), a total of 240 crewmembers and passengers were lost on the Soviet ships that were sunk in the Pacific. 145 of them perished from the American torpedo attacks.

My extensive study of the subject in 1997–99, in collaboration with fellow researchers Richard Russell and John Alden from the USA, Professor Jьrgen Rohwer from Germany, and Professor Yoichi Hirama from Japan, revealed the following findings:

1. October 4, 1943: Liberty-class freighter Odessa was torpedoed on approach to Akhomten Bay at 00:22 a.m. board time. Most likely, it was attacked by the U.S. submarine S-44. The submarine itself sank soon thereafter near Paramushir Island. Odessa, with a large hole at the stern, was towed to Petropavlovsk-Kamchatsky. Subsequently the vessel was fully repaired at the ship-repair yard constructed before the war. Odessa was last seen in Golden Horn Bay of Vladivostok as late as 2003, before being cut for scrap.

“Odessa” in Vladivostok, 2001 (photo by Alla Paperno).

2. In the fall of 1942, six submarines of Soviet Pacific fleet sailed across the Pacific Ocean, Panama Canal, and Atlantic Ocean to Polyarny naval base near Murmansk. L-15 and L-16 departed from Petropavlovsk- Kamchatsky; S-51, S-54, S-55, and S-56- from Vladivostok. On October 11, 1942 L-16 was torpedoed by Japanese submarine I-25 on the approach to San Francisco while sailing in surface position, and sank.

Monument to L-16 in Petropavlovsk- Kamchatsky (photo by Alla Paperno).

3. April 22, 1944: dry-cargo ship Pavlin Vinogradov was subject to a torpedo attack in the Gulf of Alaska at 5 p.m. board time. Most probably, it was torpedoed by Japanese submarine I-180, which failed to return to its base. Since no reports of the attack exist, its certainty is not absolute. Just like the Mikoyan and L-16, Pavlin Vinogradov was torpedoed in daylight in good visibility conditions.

Until now, these three vessels were accounted as “sunk by unknown submarines” (15). New discoveries, made in collaboration with my international research colleagues, solved another mystery of WWII.

Losses on the ALSIB Route

133 aircraft were lost on the American section of the ALSIB, and 81 aircraft lost on the Soviet segment of the route (1, 13).

American Aircraft in the Soviet Far East

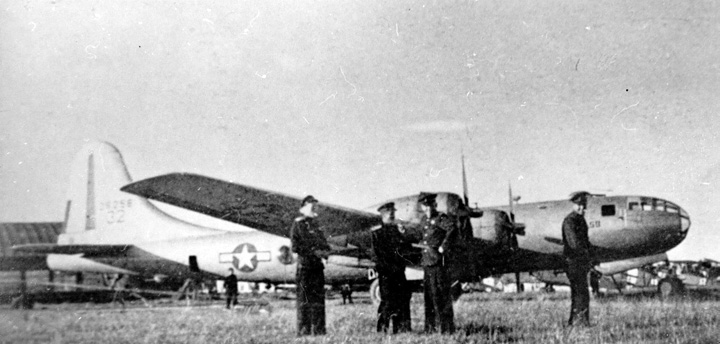

In the beginning of the war, the U.S. Government approached Moscow to allow the U.S. Army Air Corps to use Soviet airfields at the Far East for refueling after bombing missions to Japan and China. In the face of Neutrality Pact between the USSR and Japan, permission was not granted. In spite of Stalin’s prohibition, on 18 April 1942, an American medium range B-25 bomber landed at a Soviet airfield in Primorye region. That day 16 B-25s took off from the aircraft carrier Hornet and bombed targets in Tokyo, Yokohama, Yokosuka, Nagoya, Kobe and Osaka. The mission was secretly designed in response to the Pearl Harbor attack, and led by Lieutenant Colonel Jimmy Doolittle. Similarly to the Soviet bombing raid on Berlin in August 1941, it did not do much damage to the enemy, but had overwhelming morale-boosting effect for U.S. military personnel and the civilian population. The mission was nearly suicidal: the bombers neither could land back on the aircraft carrier nor could they return to the U.S. mainland due to the lack of fuel. After executing the mission, crews of 15 bombers reached China and either bailed out or crash-landed there. The only surviving aircraft was the one that landed at Soviet airfield in the vicinity of Vladivostok. In accordance with the wartime laws, the Soviet authorities interned its five crewmembers.

B-25B, AAF serial number 40-2242, piloted by Capt. Edward J. York, аt Soviet airfield near Unashi village in the vicinity of Vladivostok (via Ilya Grinberg)

During 1943–45, U.S. Army Air Corps and U.S. Navy planes regularly conducted bombing raids on Japanese fortifications in the Northern Kurile Islands from airfields in the western Aleutians. Thirty-two battle-damaged American bombers of B-24, B-25, and PV-1 types carried out emergency landing at Kamchatka, resulting in the internment of 242 American crewmembers.

Heavy B-29 “Superfortress” bombers operated from the airfields of western China against military and industrial facilities in Manchuria and Japan. On July 29, 1944, one of them landed at the Soviet air base near Vozdvizhenka village in Primorye region. Two other “Superfortresses” followed suit in November. Another battle-damaged B-29 crashed on the slopes of Sikhote-Alin mountain ridge. The crew bailed out over taiga, and wandered in the woods in separate groups for nearly a month. Eventually everyone was rescued by the combined efforts of crewmembers, local indigenous people and the VVS (Soviet Air Force).

B-29 in Vozdvizhenka (via Ilya Grinberg)

Colonel (then-Major) Solomon Reidel of VVS, ferried the interned B-29 to Moscow. Under the personal order of Josef Stalin, the aircraft was fully disassembled and reverse-engineered into the Tu-4, the first Soviet long-range bomber with nuclear-carrying capacities. The work was performed under supervision of famous plane designer Andrey Tupolev (Photo from the author’s archive)

All interned Americans were sent across Siberia to Uzbekistan, to a remote camp near Tashkent, which was established specifically for them. From there the NKVD staged four “escapes” of the internees across the border to Iran, then to the British occupation zone south of Tehran, and eventually to the USA. 291 American airmen returned home this way (5). Their return was a matter of utmost secrecy in order not to compromise the Soviet–Japanese Neutrality Pact, which was one of the fundamental conditions for uninterrupted use of the Pacific Route.

The Lend-Lease Debt

After the collapse of the Soviet Union the Russian Federation accepted the debts of all previous states that ever existed on its territory before. The Soviet Lend-Lease debt to the USA was among them. In 1975 it was 674 million dollars, but 30 years later this amount had inflated into a few billions (6*). In 1973 the Encyclopedia Americana published an article about lend-lease by Professor Warren F. Kimball with following statement: “Although all other lend-lease debts were canceled by the United States, the Soviet lend-lease debt remained as a minor irritant in Russian–American relations”(14). All the serious researchers admit that lend-lease was not an insulting form of aid. However, Professor Kimball’s point of view is rather insulting. According to his article, the Soviet lend-lease debt became not an economical, but an ideological one. The USA had canceled all Allies’ lend-lease debts, except for the debt of its ideological adversary of the time. The debt was not canceled even after the USSR ceased to exist, and the general political climate had warmed up.

At the end of October 1999, the United States Government suggested the Russian side grant them ownership of five buildings in Moscow, including the Spaso House mansion (the residence of the American Ambassador to Russia) to pay off of the lend-lease debt balance. This suggestion was not accepted. The Russian Finance Ministry’s letter № 01-02-03/26-65, signed by Deputy Minister Kolotukhin on February 12, 2003, said: “…the lend-lease payments are included in the Russian–American agreements on the restructuring of foreign debt of the former USSR signed with the Paris Club of Creditors on 29 April, 1996, and as of 1 August, 1999, … all the lend-lease payments to the American party are being paid according to the schedules of the above mentioned Agreements.”

In April 2006, the president of the Russian Federation Vladimir Putin declared that all the debts to the Paris Club of Creditors would be paid off ahead of the schedule by the end of the year. It meant that the lend-lease debt would be paid, too. In July, at the summit in St. Petersburg, it was declared that the payments would be completed in August 2006. It was done.

The lend-lease debt was paid off without acknowledgement of the fact that almost half of the losses of the Soviet transport fleet were caused by the activity of American submarines in the North Pacific.

Casualties in the Atlantic during the Lend-Lease Aid Transportation to the USSR

One more subject should also be mentioned here, even though it is not related to the events in the Pacific Ocean. It is the Allies’ casualties during the transporting of Lend-Lease aid to the USSR across the Atlantic Ocean (*7). The Americans performed most of Atlantic transportation, but only the Great Britain and the USSR calculated the exact number of their casualties.

On October 7, 1990, the Moscow News published an article “The Truth Does Not Diminish Your Sacrifice,” written by Australian journalist John Dale. He stated that over 30,000 British and American merchant seamen perished while delivering Lend- Lease aid to the Soviet Union. According to Sir Winston Churchill’s memoirs, the British merchant marine lost 829 men, while the Royal Navy lost 1,840 officers and enlisted men carrying out convoy escort duties on the North Atlantic route (15), (*8).

The Soviet Transport Fleet lost almost 1,500 crewmembers and passengers in the North Atlantic and the western part of the Soviet Arctic (12). Along with the casualties of the Soviet Transport Fleet in the Pacific Ocean, the total is almost 2,000 people.

The exact number of American casualties in the Atlantic during the transporting of Lend-Lease aid to Russia could not be found in reference books, or estimated by the American experts. Knowing the fact that American vessels transported 46.8 percent of all Lend-Lease aid sent to the Soviet Union, and the British ships constituted about 3 percent, the proportional number of casualties of the U.S. Merchant Marine could be estimated to be as many as 15,000 seamen. This number constitutes only a half of the 30,000 British and American casualties reported by the Australian journalist.

But let’s set aside John Dale’s number for a moment. Let’s suppose that the U.S. Navy losses were similar to those of American Merchant Marine: the total number of American casualties would then come up to 30,000 seamen (*9).

Additional information

A separate section of the International Conference in St. Petersburg in April 2000 was organized for my presentation of this article. The Vice-Consul of the American Consulate in St. Petersburg, Mr. Thomas Leary, attended it in person. At the opening ceremony, the representative of St. Petersburg City Administration promised to publish the materials of the Conference at the City Administration‘s official website. Unfortunately, it never happened.

After the International Conference, this investigation has been continued. In August 2000, the U.S. Navy PV-1 type bomber (Bureau Number 34641) and its seven-man crew were taken off the list of missing in action. I initiated this search in 1999 by sending videotape with a recording from the crash site to James G Connell Jr, Support Director for US-Russia Joint Commission on POW/MIAs. (Prior to that, Mr. Connell already had helped me to establish contacts with American military historians and researchers). The video contained images of the lost American bomber resting on the slope of Mutnovsky volcano in Kamchatka, with some supplemental information. Two subsequent U.S. expeditions to the site confirmed the identities of the perished crewmembers (*10).

In 2003, it was discovered, that Soviet navy cargo vessel Chukcha was sunk to the east of Paramushir Island by the American submarine SS-146 (S-41) on the night of June 1, 1943. Alexander Gruzdev, a member of the Professor’s Club of UNESCO, professor Jьrgen Rohwer, Sea Captain Anatoly Shashkun of Petropavlovsk- Kamchatsky, and myself were the principal participants of this investigation.

The Liberty-class steamer Odessa was sold for scrap metal in the winter of 2003–04. It was the last ship of the Liberty class in the former Soviet Union.

Bibliography

1. Reports to Congress on Lend- Lease operations. Messages from the Presidents of the United States, U. S. Government Printing Office. Washington, D.C. 1941–1957.

2. The Roads to Russia: United States Lend-Lease to the Soviet Union, by Robert H. Jones, University of Oklahoma Press. 1969.

3. The Persian Corridor and Aid to Russia, by T.H. Vail Motter, Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office. 1952.

4. The Battle of Komandorski Islands, March 1943, by John A. Lorelli, Naval Institute Press. Annapolis, Maryland. Third printing 1989.

5. Home from Siberia, by Otis Hays, Jr., Texas. A&M University Press. 1990.

6. Ленд-Лиз и северные конвои, 1941–1945 гг. (Lend-Lease and Northern Convoys, 1941–1945) (Мoscow, 1997, pp. 74, 79).

7. “Сотрудничество: торговля, помощь, технология” в сборнике Союзники в войне 1941–1945 (Cooperation: trade, aid, technology,” in the collection Allies in War, 1941–1945) (Moscow, 1995), p. 236.

8. АВП, ф. “Секретариат тов. В.М. Молотова” (Arkhiv Vneshney Politiki or Foreign Policy Archive), Collection of the Secretariat of V. M. Molotov, index 4, folder 104, sheet 96.

9. «ДВМП 1880-1980» DVMP 1880-1980 (Dalnevostochnoe Morskoye Parohodstvo or Far-Eastern Shipping Company), Vladivostok, 1980, pp.194, 237.

10. Государственный Архив Магаданской Области (State Archive of Magadan Oblast), Collection Р-23, including documents 4196, 4206, 4225, 4244, 4245, 4268, 4286, 4301.

11. РГАЭ (RGAE, Russian State Archive of Economics), Collection 8045, index 3, folder 1366, sheet 11.

12. Справочник «Суда Министерства Морского флота, погибшие в период Великой Отечественной войны 1941-1945 гг.» Suda Ministerstva Morskogo Flota, Pogibshiye v Period Velikoy Otechestvennoy Voyny 1941 – 1945 gg. (Reference Book “Ships of the Ministry of Merchant Fleet Lost During the Great Patriotic War 1941- 1945”), Moscow, 1989.

13. Доклад Главного управления Гражданского воздушного флота (ГВФ) при Совете народных комиссаров СССР от 8.01.1946 г. Doklad Glavnogo Upravleniya Grazhdanskogo Vozdushnogo Flota (GVF) pri Sovete narodnykh Komissarov SSSR ot 8.01.1946 g. (Report of the Main Directorate of the Civil Air Fleet (GVF) of the Council of Peoples’ Commissars of the USSR from August 1, 1946).

14. Encyclopedia Americana, Volume 17, New York, 1973, p. 200.

15. В. Черчилль, «Вторая Мировая война», сокращенный перевод с английского.

(W. Churchill, World War II, abridged translation from English to Russian, Volume 3), (Moscow, 1991, p. 621).

Translator’s remarks

*1. The Pacific Route is rather a general term often used in English literature on Lend-Lease. In reality, the delivery of aid to the Soviet Union via the Pacific Ocean was undertaken using several routes, described in details in this article.

*2. In original wording of President’s “Report To Congress On Lend-Lease Operations” the lend-lease aid was categorized as:

1) Munitions

(Ordnance, Ammunition, Aircraft, Tanks, Motor Vehicles, Watercraft)

2) Industrial Items

(Machinery, Metals, Petroleum products, Other)

3) Agricultural products

(Foodstuffs, Other)

4) Shipping and services

Source: Ninth report to Congress on Lend-Lease Operations For the Period Ended April 30, 1943. digitalcollection.smu.edu

*3. Currently Professor Richard J. Overy is with Exeter University

*4. Many Russian geographical names have more than one spelling variant in English. For example, the Strait of Tatary is often called the Strait of Tartary, while Amur Liman is russified translation of Amur Delta (Estuary). Similarly, the city of Arkhangelsk is often spelled as Archangel, especially in British literature.

*5. The Arkhangelsk group of ports includes Arkhangelsk, Bakaritsa, Economia, and Molotovsk, all located on the Dvina River within 50 km of the White Sea. The port of Molotovsk was renamed Severodvinsk in 1957.

*6. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics database and Consumer Price Index inflation calculator, 674 million dollars of 1975 would inflate to 2,526,620,000 U. S. Dollars by the year 2006. (data.bls.gov/cgi-bin/cpicalc.pl).

*7. Transportation of the supplies to the Soviet Union from North America, the United Kingdom, and Iceland via the Atlantic and Arctic Oceans and neighboring seas is commonly described in English literature as Arctic convoys, or the Murmansk Run.

*8. Hughes, Terry and Costello, John. The Battle of the Atlantic, (New York: Dial Press, 1977) indicate 30,132 casualties to personnel of British merchant ships in 1939-1945 from all causes. Miller, Nathan. Also, War at Sea – A Naval History of World War II (New York: Scribner, 1995) reports 5,151 Allied casualties in the Atlantic Ocean from 1939 to 1945.

*9. U.S. mariners suffered the highest rate of casualties of any service in World War II, but unfortunately, the U.S. Merchant Marine had no official historians and researchers, thus casualty statistics vary. The website dedicated to the history and statistics of the U.S. Merchant Marine http://www.usmm.org/, indicates a total of 171 damaged or sunk U.S. ships in the North Atlantic (1939-45). According to this source, the casualties in the North Atlantic from 1941–45 included at least 4,389 men, not counting German POWs on board the sunken ships. The data appears to be last updated in 2004–05.

*10. The events of the crash site investigation were described in details in Ralph Wetterhahn’s book “The Last Flight of Bomber 31” (Caroll & Graf Publishers; 1st edition, 2004)

Translated by Boris Ilchenko, MD with valuable contributions by James Gebhardt and Ilya Grinberg

2 comments

[…] the Second World War, the Pacific Fleet took part in operations to ensure the safe passage of US lend-lease aid to the USSR via the Pacific Ocean. Over […]

[…] the Second World War, the Pacific Fleet took part in operations to ensure the safe passage of US lend-lease aid to the USSR via the Pacific Ocean. Over […]