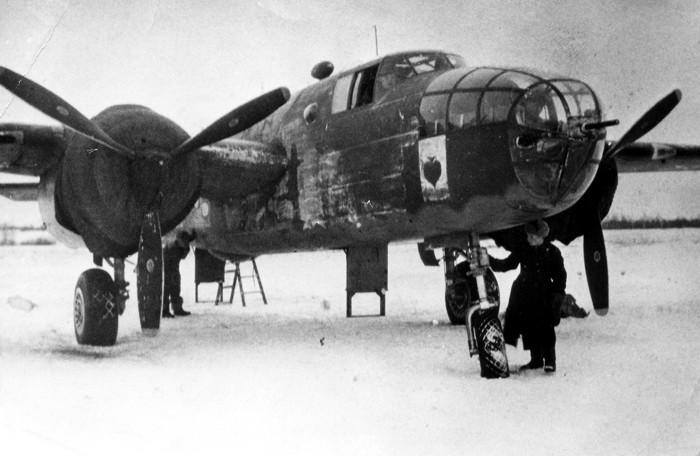

B-25 from 13 GBAP. Next to forward landing gear – right pilot Kozhemyakin.

Winter 1943-44, Novodugino.

Photo from A.Freydson archive.

My name is Aleksandr Abramovich Freydson. I was born in the city Vitebsk on 24 January 1923. My parents were in the medical field—my father was a doctor and my mother a pharmacist. Later she completed medical school.

— Where did you go to school?

I completed secondary school before the war, 10th grade. Later, in 1940, I was sent to Vol’sk Aviation-Technical School, which I completed in 1942. After that I initially ended up in a UTAP [uchebno-trenirovochnyy aviatsionnyy polk – training aviation regiment], and then in ADD [aviatsiya dal’nego deystviya – long-range aviation].

— What UTAP?

It was the 213d UTAP, which was located in the city Petrovsk, Saratov oblast.

— How were you called up [drafted]?

I was drafted in a special selection by Vitebsk gorvoyenkomat [city military commission – a local draft board].

— Tell us how you reacted to the start of the war? Did you feel it coming?

Various rumors were going around about the approach of war, but they were quite strict in the school. I even remember something that happened. We were all Komsomol members. And when one of the cadets began to express doubts, that soon there would be war, they called him before a Komsomol assembly. They wanted to kick him out of the school, just for this! But he was right; he sensed the fact, more than the rest of us, that war was coming.

We all listened to Molotov’s radio broadcast at noon on 22 June.

— And how did you react to that?

How were we supposed to react? War is war. But I think that the people did not have any idea.

— Was there enthusiasm?

Yes, some were enthusiastic, but people did not understand what war was. They did not comprehend what they would encounter when they found themselves in the active army.

— How did you end up specifically in ADD?

I came down on orders. After I completed my course at UTAP, they sent me to ADD headquarters. I arrived there, then they sent me initially to Monino, where at first I was in the ferry division, and later went to the 37th Aviation Regiment DD.

— Tell us more about your training.

At school we studied all types of technical support, the propeller-engine group, [electrical] generator group, air frame, and so on. They taught every technical specialty there. Later, in the UTAP, we studied piloting, navigational training. They graduated us as gunner-bombardiers—there was such a specialty, because we were all sergeants after completion of these courses of the 213th UTAP. Then there was a small break. They assigned me to an instructor company after graduation and held me in limbo for several months. Then they disbanded this group.

— What aircraft did you train on?

Our aircraft? The SB and DB-3. Of course we did not have B-25s. Who would use combat aircraft there? We also had Ar-2s. We had aircraft of various vintages there—we were using old stuff. I became familiar with the B-25 later, when I arrived in a combat regiment.

— Did you fly much?

We did not fly a lot. We were not involved with the pilot-training group—we worked with the navigator group. Therefore on the whole the flights were for training, and there weren’t many flights. They were conserving both equipment and fuel.

— Approximately how many hours?

I think somewhere around 60-80.

— Were they training already assigned crews? [crews that had been formed]

They trained assigned crews later, when the navigator school from Ivanovo that had been evacuated to Mari was reassembled. Then they trained assigned crews.

On the whole, we had two groups of air crews—pilots and gunner-bombardiers. And yes, the mechanics. But we were actually mechanics as well! Who pre-flighted the aircraft? We readied everything ourselves under the guidance of the aircraft mechanic. We did everything with our own hands.

— Was there some kind of special training for gunners?

In a manner of speaking, yes, but not much.

— Who was the regiment commander when you arrived?

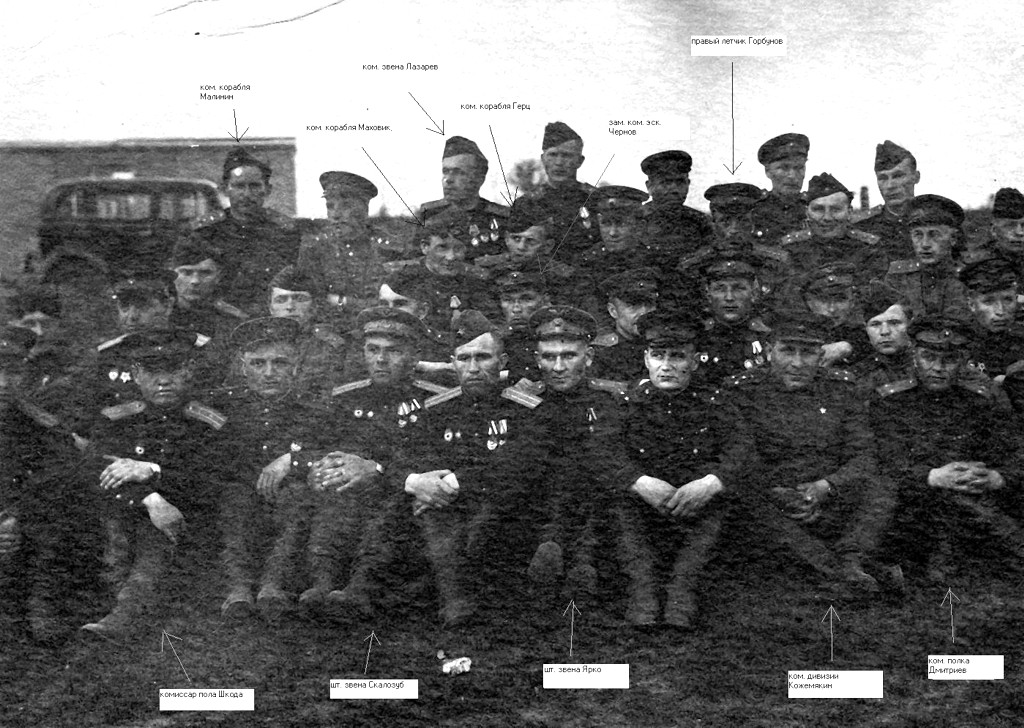

When I arrived, the regiment commander was Dmitriev. I got there in 1943. The zampolit was Shkoda.

I arrived with my orders, reported to the regiment commander. The commander looked at me, the deputy for flight operations (then it was Karasev, later Gudimov) looked at me. “You are going to 3d Squadron.” They sent me to the 3d Squadron, at that time commanded by Captain Martynov. The squadron adjutant was Seleznev. He showed me where I would live, what I should be doing, all the housekeeping issues associated with rations, accommodations, and training (not for combat, but initially for studying the equipment). We had to pass an examination on the equipment, then there were flights on a circuit, flights in the zone, and later combat missions.

— To what degree was the regiment combat-ready at the moment of your arrival?

I think that it was at 100 percent combat readiness.

— Was it fully manned with crews and did it have all its authorized aircraft?

Well, no. At that time there were 27-28 crews, because in this period before the Kursk-Orel battle, when I arrived in the unit, there had been relatively heavy losses during the attacks on airfields and railroad stations where the Germans were accumulating equipment. These places were well defended by PVO [protivo-vozdushnaya oborona—air defenses].

— What is a more precise date of your arrival at the front?

It was May 1943.

— How many crews and aircraft were in your regiment?

9 crews and 9 aircraft. We had no spare aircraft. There were two training aircraft, but they had already been “stood down”—their weapons had been removed. These aircraft had actually been taken off the property book, but you know how it was with the increase of engine hours. At first, as I recall, the regiment maintenance officer said, “Well, lets go 200 hours.” Because it was 100 engine hours on the Il-4. Then 300, 400, 500, 600, 700, 800, 900 (he laughs). The engines held up! Therefore the circuit flights and flights in zone were conducted not on combat aircraft but on aircraft that could be used for training, but which already were unsuitable for combat use.

— How do you evaluate your own training at the moment of your arrival at the front? Was it adequate?

I think I needed more training, because the equipment was new. We were not familiar with it. The speeds were so different from the old, slow-moving aircraft. This was very significant because a person had to become oriented and make decisions more quickly.

— And besides the training that you received in the combat regiment, was your general training adequate?

It was sufficient.

— How do you evaluate the general level of training of your regiment’s pilots?

I think that the pilot training was fully adequate. At a sufficiently high level. It was obvious that people took their training quite seriously. This included night flights, flights to various targets, and flights in various atmospheric conditions in which the crews might find themselves. And PVO coverage of targets, which was constantly strengthened. Sometime in the second half of 1943, the Germans began using radar.

— Excuse me, can you recall the names of your crew, your squadron, your squadron commanders, or other squadrons?

My crew commander was deputy squadron commander Guards Captain Chernov. Beyond that the names change. Sometimes we flew with two navigators. Sometimes Popkov, the regiment navigator, flew with us, sometimes Kimakin, the regiment deputy navigator—this was additional. Possibly this was because of conditions established by the command. But I don’t really know. We had several different navigators. The radio operators were Sergey Kochetov from Ivanovo, Kirin, Subotin. The squadron commander was Martynov. He was a special person whom we dearly loved. Kozlov was the 1st Squadron commander. Baymurzin later became the 2d Squadron commander. But I had three squadron commanders—Martynov died, then came Lazarev, and after him was Koryagin, who later became the division commander. At the level above them were Karasev, Gudimov. This was the deputy regiment commander for flight operations—they changed over. Kozlov also later became the deputy regiment commander for flight operations. The zampolit was Shkoda, who was a unique person. You know what surprised me? That the regiment commander conducted himself more correctly than the zampolit. The zampolit was always dissatisfied, always had a gripe about something. To this day I do not understand why he was this way. A zampolit should be a little more flexible than the regiment commander. They said that he and the commander were brothers-in-law, but I wasn’t privy to the details. I only recall that Shkoda was constantly unhappy. I had a friend, Ivan Yarkho. We were close buddies. He was a navigator, but not on our crew. He was on the crew of HSU (Hero of the Soviet Union) Mironov.

Because our crew was considered one of the best trained, we sometimes flew on special missions, but this was relatively rare. If there were difficult targets, we always participated in the combat missions. The aircraft commander was an excellent pilot and handled himself well.

— On what modifications of the B-25 did you fly?

C model. This aircraft was armed with . . . the on-board weapons consisted of one machine gun up front by the navigator, two machine guns by the commander and right-seat pilot, but they were fixed; a ball-turret mounting—by the gunner-radio operator retractable turret, and the gunner had an upper turret. This was the C-model. Later models did not have the same armaments. But these guns were not ShKASes, they were 12.7 mm [.50 caliber] heavy machine guns.

— How do you evaluate this aircraft’s engines?

I think that in their level of manufacture, these engines were significantly better than Soviet [engines]. It was a twin-row Wright Cyclone. I do not recall any failures. There were no failures. As far as the flight controls are concerned, I would say that they were at a high level as well. As for all the rest, I think that the level was adequate.

— What was the standard for engine hours?

The documents did not say. The engine hours were increased in connection with the fact that the aircraft withstood a number of flight hours. So it was like an experiment. The engine-hour ran for 200, 300, 400, 600, and 800 hours. They reached these numbers.

— Did you have cabin heaters?

No.

— How well was the aircraft equipped for winter?

Normally. But one had to warm it up. There were special methods for warming. If an engine did not start, the mechanics had to . . . It happened—a flight was scheduled and delayed, the engines were warmed, and later they had to be warmed by natural means, that is start them up, in order to maintain the temperature in the winter time.

— What was the complexity of taking off and landing and control in the air?

Well, I think that here the flight crew was sufficiently well trained. It was not just a matter of training—they gave serious attention to training in these matters at school. But here we had a conflict with our navigator personnel. Klochkov came to us (he died, and is buried at Uman’). . . Pavel Klochkov. He arrived from school, where he had worked as an instructor. He wanted to go to the front. We had conflicts with him because he lost orientation on more than one occasion, even during training flights in the zone. He got lost! He was used to low speeds. The speed of the B-25 was on the order of 450 km/h, and the SB—220-240 km/h, up to 300 km/h, no more.

— And what about the aircraft itself—was it complicated to control?

It was not complicated to control. In the first place, it had two pilots. Secondly, it had an autopilot. This was not the same autopilot mounted in the Il-4 sometime in 1943-44, but an autopilot that was built into the flight-control system. One could use it, but it was not recommended for use when the aircraft was loaded down with ordnance. There was a chance that the aircraft would come off of autopilot. I do not think that the pilots used it during the flight to the target. They used it on the return leg, but this also occasioned moments of danger. Because at that time, during the return from the mission, when we were still beyond the front line, a person to some degree dropped his guard. When the load was being dropped, you came into the zone of PVO fire, which placed no small amount of stress on a person. So a person wants to rest. Music on the radio, beaconing stations. Our communications were excellent. The beaconing station worked very well, and ground support was also outstanding. When we flew out on a mission, sometimes the target was illuminated or the direction to the target was indicated. Various means were used to accomplish this. So [on the return leg] one’s vigilance sometimes dropped and the Germans of course did not let the opportunity pass—night fighters shot down several aircraft, mainly beyond the front line. I have an impression that they (the Germans) were taught to use this to their advantage. Our crew relaxes, and the Germans start working.

— Compare the B-25 with our own ADD aircraft.

Our primary bomber for long-range aviation during the war was the Il-4. In its layout, I am comparing it visually, the B-25 was significantly better. Because first you had two pilots as compared to one. Secondly, the navigator was accessible through a passageway, he could come out of his compartment. During landing it was forbidden for him to be in his compartment—safety regulations had to be observed in these conditions. But these were not the most important things. The most important difference is that the aircraft [B-25] was more comfortable, if one can use that expression. It was laid out better; it was more appropriately built for flight from the point of view, first, of accomplishing the combat mission, and second, the aircraft was quite maneuverable.

Here is an example. Take the American Norden bombsight. This sight could not be used because when the aircraft came into the zone of PVO fires, we had to execute a counter-antiaircraft fire maneuver. When the bombardier turned on this sight, the aircraft was now guided “by the crosshairs” and you could get shot down. [The flight controls came under the influence of the bombsight, preventing the pilot from executing the required avoidance maneuver. JG]

Minimal time was allocated to the bombers for dropping the bombs. If you came into the zone of PVO fire, then several things could happen. Reshetnikov writes that they used one method. My commander did something else. When we were approaching the target, he tried to go higher. After gaining altitude he descended toward the target with engines throttled back. For example, if the bomb-run altitude was 4,000 meters, we went up to 5,000-6,000 meters. He came down into the target, accelerating the aircraft. The main mass of bombers had other flight parameters over the target—they went in on their engines, while he throttled back the engines and used altitude to gain speed. Bomb release was recomputed, we dropped our bombs, and quietly departed. He had just one unusual habit—he liked to observe the impact.

— I understand that Soviet bombsights were installed. You didn’t use the American sights?

We did not use them because they did not permit us to maneuver in heading or altitude and this could lead to tragic consequences. If one were struck in the bomb bay when they were open, the aircraft would blow up and everyone would perish.

— What other deficiencies could you identify for the B-25?

I think that the primary deficiency of the B-25 was the fact that it had less ceiling than the Il-4. And the second deficiency was range. Though Akvil’yanov, later to be the corps engineer, developed a special plan by which the aircraft expended a minimum amount of fuel at cruise speed. This was significant for extending the range. But aside from this, of course, the Il-4 had a greater radius of action than we did.

— Recall for us, please, your basing airfields.

Monino, Kratovo, then we flew to Novodugino. We were at Chkalovsk for a very brief time, then Konotop, Uman’, Kalinovka near Vinnitsa. And from there we flew to Poland and finished the war.

— What was your frequency of flight?

In regards to combat work, the following should be noted. We had a very serious problem—the fuel problem. Because the B-25 aircraft flew only on American B-100 gasoline. The Soviet Union did not produce this fuel and therefore they delivered this gasoline in small metal drums. For this reason I spoke with our chief of airfield service battalion, Major Notarius, whom I by chance met here in Yurmala many years later. I recognized him by his protruding ears. We talked about it. He said, “You can imagine how we scurried about, how we poured this fuel initially into a storage tank, then into a fuel truck, and finally into the aircraft.” This was a problem—we didn’t have enough fuel.

— So you had long breaks in combat work?

There were breaks. Especially when we were parked at Uman’. We flew to Kalinovka for refueling, and from their back to Uman’ and on a combat mission.

— What was the flight frequency when there were no fuel problems?

It all depended on the target type—close, far, or in between. If it was a close target, then we flew two sorties in one night. For example, during the Kursk-Orel battles we flew two sorties per night. After we moved to Uman’, we began to fly to deep targets: Constanza [Romania], Galats. Then, of course, one sortie per night. But all depended on fuel. The length of a sortie was 2-3 hours at a minimum, and 8-9 hours maximum.

— What was the maximum range of any sortie you had to make?

2,000 km there and back, sometimes even greater.

— What kind of target?

Koenigsberg, Tilsit, Danzig, Budapest, Galats, Constanza. Budapest was especially far. That is where they shot down Lazarev (D’or)—we were flying from Kalinovka.

— What kind of supplementary or drop tanks did you have?

We had only wing-mounted drop tanks. They were made from cardboard, specially compressed cardboard.

— What were your shortest flights? Did you conduct bombing along the front line?

Yes, we flew some of those sorties. Golovanov writes about this. These flights were connected with the breakthrough of the defenses by our troops in the west. When the operation in Ukraine began, there were sorties in the forward area, in specific regions where the Germans had fortifications, DOT, and where we used special ordnance. We used RRAB against airfields, 5-kg high-explosive or incendiary bombs that were contained in a special casing. This RRAB was dropped, it spun around, then exploded, and these bomblets were dispersed across the ground. This ordnance was very effective against airfields because it permitted the destruction of a greater quantity of enemy equipment.

— Bomb load: type of bombs, weight of bombs, total load, influence of load on range?

The normal total bomb payload was up to 2 tons. The closer the target, the more bombs we could carry so long as they fit into the bomb bays. We normally did not use [external] hangers, because that would have reduced our fuel load, and vice versa.

— What bomb load did you carry against distant targets: Koenigsberg, Tilsit?

A ton and one-half. We could not carry any more—it would not be enough fuel.

— And against the closest targets?

Two tons, guaranteed. But some carried two and one-half, although with some risk.

— Types of bombs?

FAB, SAB, if we went out as the leader, FOTAB if we went out as the photo aircraft, ZAB, concrete-busting bombs, bombs with double explosive force, so-called TGA, these are examples of the types. They came in various calibers [weights]. Sometimes 500-kg were hung, but this was rare, when we were going to a target like Koenigsberg, we used only 500-kg. The special TGA were used to break concrete reinforcements. We usually dropped RRAB on airfields because they had the greatest destructive force for conducting strikes against the aircraft that were located there.

— Did you (your regiment) conduct daylight bombing?

Our regiment began to fly daylight raids only in 1945. At first this was interesting. No one knew how to fly in the daytime—people were unprepared. Later we began to train for it—we walked around the airfield; they showed the crews how they would conduct themselves in the air. Flying to achieve a level of coordination was not performed. It seems they were conserving fuel.

— Was your first daylight raid on Koenigsberg?

Our first daylight raid was on Breslau. We made 5-6 sorties there, as I recall. But this fact is not the most interesting. The most interesting fact is that we worked on it for quite a long time. We had to fly to the targets by squadrons. And when we approached the target, then we actually dispersed. We were not used to flying “by squadron.” (laughter) Incidentally, Baymurzin was shot down there. A “Messer” or “Fokker” jumped up and cut into him. He landed his burning aircraft.

— Landed or bailed out?

Landed, landed.

— No one died in the crew?

No one died, but fact remains fact—he was shot down there.

— What improvements did the Soviets make to the B-25? You have already mentioned the sights. Did you make changes to the gun turrets?

No. But we did install Soviet electrical bomb-releases. The Americans had their approaches to this task, but it was believed that ours held the bombs more rigidly.

— What can you tell us about the navigational equipment?

I think that the navigational equipment was of quite a high caliber and supported both day and night flight. Especially night flights. Sometimes the aircraft entered conditions when we did not have visual orientation. We could have used astrological navigation, but the navigational equipment of the B-25 was good.

— Did you often stray from the navigator’s course?

There were instances of wandering off course, but they were very rare. If the navigator got off azimuth, the radio operator took a radio heading and we came to a specific point from which it was easy to reach our own airfield.

— Did you ever land at someone else’s airfield?

There were such cases, but they were very infrequent.

— What about aerial photo control? What cameras did you use?

We used Soviet cameras. We conducted aerial photography with the aid of FOTABs. But you are talking about the use of photographs to confirm the results of the regiment’s work. There were no cameras on regular aircraft. Only the regiment’s aerial photograph aircraft had cameras. It was required to photograph the target depending on a number of factors associated with altitude, heading, and the dropping of FOTAB, which sometimes themselves did not detonate. This forced the crew to go back over the target. As soon as the FOTAB went off, the photo element was opened, the lens was uncovered, and 8-10-12 photographs had to be taken. The time for this was very brief. The first pass, then the second pass—that was all. One could not make a third pass because the following regiment was coming and they were dropping SAB [illumination bombs]. Then all the photographs would be overexposed.

Because I had to fly on photographic missions with Baymurzin, I remember these times well. They were relatively serious and complicated. When we got to the target, it was quiet over the target. Our regiment had already dropped their bombs and left and we were coming in to take the pictures. As soon as we dropped the second FOTAB, immediately the enemy opened up with barrier fire in order to shoot down our photo plane. It was clear why they were doing this. We either had to depart or turn into the second circle. But sometimes it was simply impossible to commence the second circle because the [antiaircraft] fire had increased to greater levels. The enemy’s desire to shoot down the aerial photo plane was, I think, stronger than necessary. We needed to “thread the needle”, however shells were exploding nearby. The engines were working and you could hear a sound like BOOM-BOOM-BOOM—this meant the shells were exploding close. But we had to and did pass through it.

— Were there cases when the crew did not take the pictures?

I don’t know. It never happened with us.

— How many combat sorties did you fly?

Somewhere around 105.

— Were you ever shot down?

Suddenly, as if something was beginning to tear—you know that sound, like fabric ripping. And firing from the radio operator’s machine gun. What’s going on? The commander says, “They have shot us down! Bail out!” Well, we abandoned ship. I ended up in a medical battalion because I had a contusion. How they landed the airplane—I had no idea. Had the commander survived—we did not know. I spent about a week in the medical battalion. I saw terrible things there, of course, things that we rarely saw in aviation.

— Who was your commander at that time?

Our commander was Gerts—my last commander.

— What happened to him after that?

He safely landed the aircraft. On its belly. He made a classic landing; he himself was not injured. This was already in the morning, therefore it was already possible to orient oneself on the ground. I figure that is what saved him. Later they raised the aircraft up and flew it out. Naturally, the propellers were bent.

— Where did this happen?

It was while returning from Sevastopol. Sevastopol was the target.

— How do you evaluate the counter-actions of the antiaircraft guns and fighters?

The German PVO tactics varied. They included the following: there were three elements—antiaircraft artillery (MZA worked at low altitudes), fighters, and searchlights. The most important consideration was that the Germans worked very effectively on searchlights, but fired badly. This is an opinion shared by many, not only mine, perhaps (laughter). The first salvo was crucial. If the first salvo did not hit you, you were more or less safe. But if the first salvo struck, consider yourself already on fire. There was a main searchlight. They called it “Ivan”, “Vanyusha” [a diminutive of Ivan], or simply “Main”. It was the most powerful and conducted the search for aircraft.

When there were sound-distance stations, it was simpler for us. And when radar appeared, then PVO operated with good coordination. Fighters worked the approach and departure airspace if there were any based in the area, and antiaircraft gunners covered the area above the target. Or vice versa—they changed roles. If antiaircraft positions suddenly ceased firing during a combat sortie, it meant that there were fighters in the air.

— What kind of maneuver did you use to get out of the searchlight beam?

The escape maneuver was a sharp reduction in altitude with departure away from the target. This was the most favorable and successful way out.

— How do you evaluate the work of the enemy fighters?

I think that the enemy fighters were quite active. There were cases when they were engaged in “free hunt.” We used “free hunt” as well, but much less often than massed raids. Individual crews were sent out on free hunt—if there was a train moving or a small airfield (one could be shot down in an instant over a large airfield).

— How often did you have to conduct aerial combat?

I will not tell you that it was often, but there were cases. To some degree this was a kind of game.

— What type of fighters did you encounter?

Primarily Bf-109s.

— And the 110? [The Messerschmitt Bf-110 was the Germans’ primary night fighter.]

There were one or two encounters. You know how they turned out? The commander immediately threw the aircraft down and departed. He changed course, and then again returned to course. We somehow encountered a Ju-88—we came out of the clouds and there he was. He opened fire, we did the same, and we both departed in different directions.

— Tell us about the time when Krapiva shot down an airplane.

This is only based on stories I heard. He told it this way. “Returning from a combat mission, we suddenly came upon an active German airfield. Bombers were in the pattern—landing. I gave the command, ‘Get in the pattern.’ We began to close up on a bomber. They turned on their ANO and I turned ours on. I gave the command, ‘Fire!’ and opened fire from the forward machine guns. The navigator also began firing. And we shot him down.” This is what happened.

— What were your losses by periods?

Losses were relatively significant in the Kursk battle because the PVO over such targets as Bryansk, Orel, Seshcha, Balbasovo, and other places was very well supported by heavy antiaircraft artillery and fighters. At the same time, trains with reinforcements, equipment, and fuel were moving through station junctions such as Gomel’. The ADD staff correctly planned the conduct of strikes, but losses there were unavoidable because of the great strength of the PVO, especially fighters.

— And after that? During the liberation of Ukraine? Did losses increase or decrease?

Our losses decreased. Well, there was Sevastopol, which now is also Ukraine. We had significant losses there as well.

— What were your losses during sorties to long-range targets?

Danzig, Koenigsberg—there were losses, but not too many. 2-3 crews were shot down.

— What was the level of losses during daylight sorties?

Well, we had Gorlov blow up on the last sortie to Swinemunde. War is war—losses are unavoidable.

— But on the whole, losses did not increase upon the transition to daylight sorties?

No, they did not increase. They actually were reduced. Because Soviet aviation already had air superiority and the Germans had limited possibilities.

— Did your regiment participate in sorties on Helsinki? What were the targets? How do you evaluate the PVO of the city?

I will say this. We had strategic targets: industrial facilities, the port. But in no case the residential sections—it was forbidden to drop bombs there. Regarding the PVO, I made 5-6 sorties there. At first the PVO was disorganized. The [ground] fires were visible for 200-250 kilometers. Later the PVO worked more effectively, was more coordinated. But there were no fighters there, only antiaircraft positions.

Pilots from 13 GBAP, Kratovo, 1943.

Photo from A.Freydson archive. (Click to enlarge).

— Describe the relationships between crew members.

I can only tell you it was good. No scandals, no conflicts. And I’ll tell you the something else that is not recorded in any documents. If something happened within a crew or someone was guilty of something, then no one anywhere ever reported it on an official level. We had a situation develop in Novodugino. We took off, and 5-7 minutes later our radio quit working. As we returned to base the regiment departed on the mission. During our approach to the airfield the [aircraft] commander said to ground control, “Our radio quit working.” “Are you loaded with bombs?” “Yes.” By flight regulations we should have jettisoned our bombs in an “unarmed” condition. They gave us permission to land and we quietly landed [without jettisoning the bombs]. The radio mechanic repaired the radio and we took off on the mission. And no one knows anything about this incident. If we had jettisoned our bombs in an “unarmed” condition, it would have been a disaster. It would have been an uncompleted mission and our radio operator would have been hauled before a military tribunal.

Then there was Prokhorov. I remember this incident because our aircraft was parked nearby. He taxied to his parking spot, crawled out of the aircraft, drew his pistol and said, “I’m going to shoot them!” It turned out that the bomb handlers, when they hung his bombs, had forgotten to turn out the overhead light in the bomb bays. And when the navigator-bombardier opened the bomb bay doors, the aircraft became a beautiful target. But Prokhorov did not place anyone on report.

The happiest person in our regiment was navigator Aleksandr Rustamyan (unfortunately, he has passed on). At the most critical moments he could make a joke and brighten the mood, especially when someone failed to return from a mission. This is what happned with Gorbunov. When he received his third Order of the Red Star, he said, “Guys, why do they treat me so disgracefully? Why can’t they give me an Order of the Patriotic War?” Rustamyan stood up and said, “Kolya, you know why? Because you have red hair!” And indeed, he did have red hair (laughs).

— How did you accept the death of comrades?

It was a tragedy. We worried sick for them.

— Did you know pilots who were taken captive and returned after the war? What was your attitude toward them?

For example, our squadron navigator Semen Nechushkin, Lasarev’s navigator. He received 25 years as a traitor to the Motherland. The counterintelligence people were interested in making up his case. Attitudes toward prisoners of war were bad. There was also Rud’yev, Martynov’s gunner-radio operator. He also survived (but died later in an automobile accident in Aleksandriya). When I met with him I said, “Pasha, well, tell me what happened to you.” He simply broke down crying and did not say another word.

— This was the attitude of the authorities. What was the attitude toward them among their comrades?

I would not say that it was negative. On the contrary, it was positive. Concerning those who were shot down and not captured, what is there to say? They returned to us and flew again. But in regards to the captives, take Rud’yev, for example. They began to say that he ostensibly completed some [German] intelligence school, but I could not imagine that a person who had fought almost through the entire war could do something like that.

— Tell us about the death of Lazarev.

I only know bits and pieces of the story. We were flying to D’er, in Hungary, to bomb a railroad station. How did this happen? I really can’t say. No one expected it. When we arrived back from the mission the radio operator reported that Lazarev had been shot down. No one knew the details except his navigator, who survived but was captured.

— And the rest of the crew?

We heard nothing about them.

I was acquainted with Lazarev’s son. He came to meet with us and wanted to learn where his father’s grave was located. We raised the question regarding Lazarev’s grave, and also about Nechushkin. When it was revealed that Nechushkin had been convicted by a special session [of the tribunal], it became clear that he was guilty of nothing.

— Did you ever have to fly with serious damage: on one engine, with damaged flight controls?

It happened a couple of times. An antiaircraft round struck an engine over the target. The engine seized and we continued on the other engine. But, thank God, this was not too far from the front line. We landed on one engine—it was a normal landing.

— How was the aircraft controlled with one engine?

The aircraft commander feathered the propeller and attempted to hold the aircraft on heading with the aid of the trimmer, but we lost altitude. One can do this with sufficient altitude.

— And were the controls heavy?

Yes, heavy. But the most important moment was in the landing. Normally in such cases the flight director issued the command, “Everyone clear the pattern! A damaged aircraft is coming in.” And this opened up the way for a straight-in approach and landing. This was the correct decision. Don’t even think of making a normal approach from a circle. One could rollover or get into some sort of an accident [with damaged plane].

— Tell us about your most interesting flight.

I think this was the flight to Budapest. When we arrived at the target, the city was lit up [as in “not observing” blackout]. They did not anticipate the arrival of bombers. Even when the leader dropped an SAB [illumination bomb], they did not turn out the lights. When we began dropping our loads, then the antiaircraft guns began to fire. But they were shooting wildly, not organized at all. The searchlight operators were in panic mode—there was no unified air defence system for the city.

— What airfield did you fly from for this mission?

From Uman’. It could have been Kalinovka, but it seems to me that it was Uman’.

Then there was Radom airfield. What was interesting about this sortie? The Germans had concentrated 250 bombers there, according to some reports. Our division and two regiments of the neighboring division operated against it. The peculiarity of this target was that the airfield was relatively large in territory and our aircraft were concentrated in regiment-size formations. Each division and each subordinate regiment was assigned specific area targets. They were illuminated by various SAB, for example SAB with green, SAB with red, SAB with yellow—and the crews knew which target was theirs. The altitude and course heading for the target were determined in such a manner as to prevent mid-air collisions. The timing of the attack was also calculated. This was all very interesting. Resistance was not anything special, though the antiaircraft crews, of course, did fire at us.

— And the results?

150 aircraft were destroyed.

There was another incident, most interesting. It was at Osipovichi. There in the woods, according to reports from partisans, was a front-line artillery depot. We flew there three times. And three times the photographs showed burning tar barrels and nothing else. The corps commander gathered all the men together: “Comrades, why can’t we find it?” The depot was located in the forest and it was impossible to find it from the air.. We had a deputy regiment navigator, Ivan Yevstaf’yevich Romanov, among the most experienced navigators. He stood up: “Comrade General, may I say something?” “Yes, what do you suggest?” “I will go as lead navigator.” “Well, an old horse won’t spoil the furrow.” “And it plows deep.” Well, Ivan Yevstaf’yevich, you will earn the Order of Lenin if you come out precisely at this target.” This is how the conversation went. As the members of his crew described it, it was a very interesting sortie. They arrived over the target, the division was in the air, the time of the strike had not been set because the SAB were not burning. The leader flew a square and at each corner dropped a single SAB. No reaction. Well, perhaps a battery of antiaircraft guns opened up, but this was not an indicator. Then he decided to cross on a diagonal. He flew across, again nothing. He turned around 180 degrees and made another pass, dropping an SAB. It all began there. Then he dropped a whole series of illumination bombs. The very first bomber made its pass. You know how the sun rises? That is the kind of explosion that resulted. The rest of the bombers simply dropped their loads, but it already did not matter where they fell.

— Did you participate in the dropping of diversionaries?

Lazarev primarily carried out General Staff missions. But we sometimes executed these sorties as well. There were flights to Germany, to Poland, a pair of flights to Romania. The conditions were the following: when the aircraft was to go on a special mission, the regiment commander summoned the aircraft commander and said, “Today you are flying to . . . “ Everyone else cranked up their engines and they asked us, “What are you doing?” “We’re resting. Something is broken.” They all taxied out to the launch point and then took off. When they had all left, then the regiment commander came over, trailing a closed bus. There were 2-3 persons on the bus that we were to drop. An officer arrived with them. Right then and there our aircraft commander received the mission: drop at such-and-such location, at that place would be some kind of signals, and nothing more. These people normally sat in the navigator’s compartment. There were several instances when these people opened fire on the crew. Therefore the right-seat pilot was to be on guard. We arrived at the target, where we spotted some kind of light signals or fires, generally some type of burning spots. We dropped them on a single pass or on two passes, first their cargo on parachutes and then the passengers themselves.

— Talk about operations to supply the Slovak uprising.

This is a special story. The operation unfolded in the following manner. Some kind of crates and boxes, covered in canvas, arrived at the airfield. Later talk went around that we would be flying a special mission. Where? For what? No one knew anything. The best crews were selected out. Some khaki-colored cigar-shaped bags containing ammunition, medications, and weapons were loaded up. They stowed them in the bomb bays, hung them on the electric bomb releases and these were to be dropped over the target. But there was a complication. Zvolin airfield, Tri Duba as the locals called it, was on terrain located in the mountains. We flew from Kalinovka airfield; this was September-October 1944. In order for us to reach the target, one crew was sent out to mark with SAB the pass where we could get through the mountains. Later we gained altitude above the mountains. We came out, turned 90 degrees, and there was Zvolin airfield. We could not drop the cargo from high altitude on parachutes for two reasons: it could be damaged upon landing, or it might fall on enemy territory—the Germans were nearby. Therefore the aircraft spiraled down, dropped its cargo, and departed in the same manner. Normally there was a leader over the target who directed specific crews by radio command. This was to prevent mid-air collisions. Although the operation was rather complicated, we did not have any losses there.

— How did you get along with the “osobist”?

We lived with one unfortunate woman in the village Sliznevo, 22 kilometers from Novodugino airfield (or Sychevka, they called it both). They drafted her son. This had been occupied territory, and then a particular procedure was followed. The military commission sent all the men of draft age to the front, where they died for the most part. And this woman asks me, “When will you go into the barrel?” Into what barrel? I did not understand what she meant. “Well, you’ll see, all the pilots now are going into the barrel.” We knew nothing. It turns out that our counterintelligence agent [osobist] reported to the regiment commander that in the forest tract, where we went to dance, ostensibly Vlasovites had appeared and we have to set up a stakeout. On the edge of this village (a small, poor Smolensk village) stood two bottomless barrels. They began to stand guard at this barrel. Well, who did not know about this? In the village everyone knew everything! (laughs) Then on some night, at 4:00 in the morning, firing! Well, everyone ran to the headquarters, where the regiment commander lived. Dmitriev ran out, it was winter, in his great coat, hat, fur-lined boots, and underpants. He had not managed to put on his trousers. (laughs) The officer on duty at that time was this same counterintelligence officer, Captain Kolomiyets. His hands were shaking. He said, “Comrade Guards Lieutenant Colonel, Vlasovites came at me and I fired!” The regiment commander walked straight over to the barrel to see what had happened there. There were two friends in the stakeout—Prilepko and Trotsenko. They are sitting in the barrel and smoking. “Guys, what happened?” “How would we know? The duty officer walked over, we were walking, we looked around, there was no Vlasovites. And suddenly firing! What’s going on? We did not understand what was happening.” The men will make up such a story, you know how . . . And it turns out that when they saw that the captain was coming (he used a flashlight at night), they crawled out of the barrel, hid behind the barrel, took a limb from the woodpile, and when he crawled to the barrel and began to call them, they began to beat on the barrel with the limbs—this made a thumping noise and the captain opened fire. The regiment commander said, “Comrade captain, how you have misled us. . . Well, was this possible?” (laughs) This actually happened! Our relationship with the osobist developed from this. Reshetnikov writes that they were beasts. But ours conducted himself more quiet than water, lower than grass. In general he did not interfere in our business. There were times, men have said, when he invited someone “to tea”, but what kind of information could they have given him? About what? What could they have said? What kind of a mindset people have? Well, someone loves to drink—things of this nature. (laughs)

There was a case with Subotin, born in 1926 [a reference to his youth—18 years old in 1944], gunner-radio operator (now he is a colonel-engineer, lives around Moscow). He had just arrived in the regiment and he made his first combat sortie in our crew. Afterwards, we had already arrived on Studebakers from the airfield, and were sitting around the table. We had already drunk our 100 grams [daily vodka ration] that the squadron adjutant had given us. Our aircraft commander had a bottle, our “crew ration”, that was used as a de-icing fluid. He poured us a drink, but not the radio operator. “Commander, what about me?” “This was your first combat sortie, there is no extra for you. You already had the vodka, so be grateful for that” But he bragged and bragged, so the commander poured him a little glass. When he had drunk this alcohol, he became exceedingly drunk. His first sortie made quite an impression on him! When he got up from the table, the osobist sat in the corner at a small table. This radio operator was a big man. He knocked over the osobist and his table. The osobist ended up on the floor. On the next day, at formation, the squadron commander Martynov says, “Sergeant Subotin, two steps forward!” The sergeant stepped out. The squadron commander says, “Sergeant Subotin, did someone die?” “No one, Comrade Guards Major.” “Perhaps someone is ill?” “No.” “Perhaps you have fallen in love with someone?” “No.” “Well, how was it you did not notice our esteemed captain?” (laughs) The entire squadron broke out in laughter. This happened.

— Were there any superstitious signs at the front? Had you ever been confused by the number of your regiment?

Concerning the number of our regiment, there was some talk. Well, 13th Guards. Everything was OK. (smiles) There were signs. We went to the airfield by bus—we did not take a woman with us, otherwise someone might be shot down. We wouldn’t shave before a sortie—we might be shot down.

— How did you accept subordination of ADD to frontal aviation?

I think that this was humiliating. The humiliation consisted in the fact that we did not know the reason for this decision. People have written various things about it. But I think that this was not correct. Subsequently ADD was reestablished.

— Do you remember any peculiarities about the aircraft painting? Camouflage, numbers, their place, size, color? Were there stars on top of and under the wings, painted propeller hubs or leading edge of the tail assembly? Guards emblems on the sides, orders, emblems, drawings [as in “nose art”], and so on.

Guards emblems we had, and camouflage. In winter we painted the aircraft with a weak solution, not quite pure white, like oil-based paint. We did not paint the propeller spinners—they were normally black.

— What about emblems?

All sorts of emblems.

— What did you have, for example?

We had an eagle. It’s still funny—a “wet flying chicken.”

— What else was there?

I remember a lion. Lazarev had a ballerina. This was a gift of American artists to Soviet pilots; they had given it this name—Ballerina. There were many other emblems. Everyone thought of some kind of wild beast for their emblems. On one side was the guards emblem and on the other—a drawing.

— Was there a system for assigning bort numbers [not the factory-painted tail numbers we are familiar with, but the unit tactical number, normally between the cockpit and the tail]?

The regiment HQ was responsible for this.

— Could the pilots select their own numbers?

No. The command determined this number. The aircraft number was its call sign during conversations over the command frequency. Each aircraft was named “Falcon”: “Falcon-9,” “Falcon-10,” and so on.

— Did you receive later modifications of the B-25?

We did not have “Dragons,” but we did get the C model. That is what Lazarev flew. [According to the photographic record this regiment was equipped with B-25D and B-25J aircraft as is evident from Red Stars 1 and Red Stars 4 books. Another example of this is http://lend-lease.airforce.ru/english/photogallery/b-25/b-25_09.htm, where the serial 42-87594 was allocated to B-25D-30 –I.G.]

— Did you have any aircraft that were completely painted in black?

No.

— Were your auxiliary fuel tanks only cardboard? Did you have any that were mounted inside the fuselage?

No.

— Do you remember any specific cases when diversionaries [saboteurs] fired at your crew?

They talked as if there was such a case, when during the delivery of a special group to a target area, one of the members of this group opened fire on the crew. And after this incident, an order was issued that during the insertion, when the hatch was opened, the right pilot should exit with a pistol in his hand and escort the passenger(s) from the aircraft.

— Who were the HSUs [Heroes of the Soviet Union] in your regiment?

Kozlov, Lazarev, Baymurzin, Zhuravkov, Tyurin, Taygunov, and I’m not sure about Mironov, whether he received it while assigned to our regiment. And Krapiva. Eight men, I think.

[Editor’s note: Iosif Dmitriyevich Kozlov (13 March 1944), Ivan Aleksandrovich Lazarev (5 November 1944), Gayaz Islametdinovich Baymurzin (5 November 1944), Mikhail Vladimirovich Zhuravkov (19 August 1944), Leonid, Fedovovich Tyurin (19 August 1944), Nikita Andreyevich Krapiva (5 November 1944). Taygunov and Mironov not found.]

— Where were the crews trained: in a UTAP, ZAP ? [UTAP is a training aviation regiment and ZAP is a reserve aviation regiment-translator]

At that time we had a special school in Central Asia where they trained crews for ADD. This school where they trained crews was created on the initiative of Golovanov. I did not get training there.

— Did everyone you trained with at the UTAP go to another place?

Yes.

— How long did you have B-25s in your regiment after the war?

It was somewhere in 1949-50.

— Did people come to the regiment who had flown on the Il-4, Er-2, Li-2?

In my experience, this is how the crews were made up. A portion arrived from civil aviation, pilots of GVF [civil air fleet]. And military pilots who had completed flight school. Navigators? Our navigators were from the Chelyabinsk navigator school.

— Did crews come in from other regiments?

Not normally.

— Was there anyone left in the regiment who was there at the start of the war? Chernov, for example?

Chernov was in another regiment. But he flew with us all the time, from the moment when the regiment was equipped with the B-25.

— But was there anyone left in the regiment who had flown on the SB?

Dmitriyev was a political officer—our regiment commander. He was in Kuybyshevka-Vostochnaya, where the regiment was based in the Far East, and arrived at the front together with the regiment. There were just very few others who stayed behind and survived, because on the whole the regiment lost its entire complement of personnel.

— Were the corps’ formations based in close proximity to each other?

I think so, on two-three airfields. Only not the corps but the division. The corps only appeared at the end of 1943. Just the same, we were not far from each other: we were stationed at Uman’ and they were stationed at Kalinovka (neighboring division), and the headquarters was in Vinnitsa.

— Did you exchange visits with the pilots and ground crews of other regiments?

Absolutely, we co-mingled with the pilots of other regiments and even form other divisions. Here is an example. At Kratovo, a regiment of TB-7s was on our left side, Pusep was remarkable. By the way, Vodop’yanov served there, whose sons were mechanics on his aircraft. They had a saying, “Well, Mikhail Vasilich, why aren’t you protecting your sons ” His response was, “This is my guarantee, since they are with me—it means my aircraft will be in tip-top shape.”

— Did you sortie on a mission in a mixed group?

No.

— Did the work with foreign equipment raise the general “technical culture,” as one would think it would?

I think so, yes. It improved.

— How about flight clothing. What did you fly in?

That’s an interesting story. The Americans sent the aircraft with a complement of flight suits—jacket and pants—made of monkey fur.

— Monkey fur?!

Yes, monkey fur. But we largely did not receive this clothing. It was a rare person who had the American gear. We flew in our coveralls with high boots. Then there were helmets as well. Many said, “Look at me, I’m putting on my helmet.” We didn’t have anything like it. You wore earphones and on top of them a simple hat. It was more comfortable. When you wore a helmet, your ears were pinched. It was uncomfortable.

— Whose helmets?

Ours, ours. They issued us fur socks as well—“untyata” they were called.

— So this means that lend-lease didn’t quite make it to you?

Well, we saw that when some higher brass arrived—they were walking around in these leather suits.

— Did you fly in your coveralls in the winter?

In the winter. And in the summer we flew in lighter coveralls, they were made of quilted fabric, I think, and in boots.

— What other lend-lease equipment did you encounter? Trucks?

The Willys were for the leadership. They hauled us around in the Studebakers, normally to the airfield and back if it was any distance.

— Radio equipment?

Of course. Our radio operator had Bendix radios with removable blocks.

— The Norden was considered to be a quite modern sight. Why was it not used, at the very least by the leaders?

The Norden sight was an automatic sight, and as a result of its use the aircraft could not make a genuine counter-antiaircraft maneuver. The aircraft could be simply shot down.

But the leader flew in the lead and they opened fire on him when he dropped the SABs.

We often worked as part of a division. The regiment might be the leader, another time we could go as number 2 or number 3. Then antiaircraft artillery worked everyone over. Therefore the Norden bombsight was seldom, if ever, used.

— You have met Golovanov [Commander-in Chief of ADD]. How do you evaluate him personally and his activities as a commander?

Well, what can I cay about Golovanov? Reshetnikov [HSU, Il-4 pilot, in 1970 – 80’s – Commander-in-Chief of Long-Range Aviation, author of several memoirs] has written that in some respects, here comes someone whom we did not know. I don’t find these remarks very convincing. He was, after all, the commander. And there are contradictions in Reshetnikov’s book. On the one hand he writes that we are “long rangers” and here is someone who came out of the GVF [civilian air fleet]. And on the other hand, he writes something else—first that Golovanov built ADD on a broad base and second, with Golovanov’s arrival and the creation of ADD, the aircraft were transitioned to night flights, which sharply reduced our personnel losses. Some people say that you can see during daylight and see nothing at night. Rubbish! One could see at night as good as in the daylight if there was good illumination of the target. Now about Golovanov himself. Take his book, Dal’nyaya bombardirovochnaya [long-range bomber (aviation)], which was published in the journal Oktyabr’, I think sometime between 1967 and 1972. They did not publish the book. He very objectively, very correctly, very fairly and honestly wrote about what happened. I believe that his book is one of the best books written by an air army commander. This is an indisputable fact.

— Tell us about your meetings.

I will tell you about Konotop. This was very interesting. During the daytime pre-flight preparation, the aircraft stood in a line, and this line was located alongside the landing field. Suddenly an aircraft landed with the number “1” and a red and gold stripe. Everyone was bustling about: “Golovanov has arrived! Now the fun will begin!” At this time they were feeding us rice three times a day at Konotop. Rice soup, rice porridge, and so on. The pilots spent several hours in the air and rice will cause constipation – there is nowhere to go during the flight. Golovanov taxied to the parking area and came over to check on us. He asked us: “Comrades, how are your accommodations?” “Everything is fine, comrade commander.” “How about your rations?” No one said a word. Well, he was no fool. He understood that everything was not fine in the rations department. Then it came time to go to dinner. They fed us in two shifts—the dining hall was small. A crowd of men walked into the dining hall with Golovanov in the lead. As we later found out, Golovanov had forbidden the flight operations officer from informing the division commander of his arrival. And now a crowd has arrived at the dining facility. There sat Prilepko, who at the time, I think, was a Starshiy Leytenant. He was getting ready to eat when someone slapped him on the shoulder. Prilepko [apparently not looking up] said, “What? You want to eat?” Someone slapped his shoulder again: “Comrade Starshiy Leytenant!” Prilepko turned around: “Comrade commander???” Golovanov tasted the first course and then the second course. Then someone reported to the division commander that Golovanov had arrived. The division commander ran into the dining facility and commanded: “Attention!” To which Golovanov replied, “Comrade Polkovnik, they do not issue that command in a dining facility. At ease! Airfield service battalion commander, report to me!” This officer reported. Golovanov asked him, “Comrade Mayor, what are you feeding my pilots?” “According to the fifth norm, Comrade Commander.” “Stop serving this meal! And prepare a normal meal according to the fifth norm!” Then, in a quiet voice, without shouting, he said, “Comrade Mayor, if you repeat this practice, you will find yourself in a penal battalion.” That settled that!

[Translator’s note: During the war, rations were allocated to units in accordance with their assignment and proximity to the front. Front-line units ate at the high end of the ration scale and rear-echelon units at the low end.]

Here is what happened after dinner. They assembled us at an open stage, where there were long wooden benches. They set up a presidium, a table with a red tablecloth. General Gur’yanov, who was a member of the ADD Military Council, and the adjutant sat there. The adjutant had some kind of bag. Golovanov sent the division commander and regimental commanders away. Kozhemyakin asked, “Comrade Commander, why do I have to leave?” “Comrade Polkovnik, I said ‘You are released.’” He did not shout; in general he did not have a habit of raising his voice. Quietly and calmly he repeated himself and the commander left the area. Golovanov stood up at the lectern and asked, “Comrades, what are your questions?” No one said a word. “Comrades, does anyone have any complaints?” That is how it was: he first asked for questions, and then complaints. A hand was raised. “Comrade Commander, Leytenant so-and-so. My aircraft commander has completed [a stated number of] combat sorties, and he has such-and-such awards.” “Repeat his last name!” The officer stated his commander’s name again. “Come up here!” And at this time the member of the military council wrote something down. Then he said, “In the name of the Military Council of ADD, I award you with the Order of the Red Banner.” He presented the officer with the award. He dispensed additional awards using this public forum. Then they invited the division commander back. He asked, “Why did you give out these awards? That is my responsibility!” To this Golovanov replied, “Polkovnik, I do so because you are not fulfilling your responsibilities.” Kozhemyakin was very stingy with awards. This was the first time I had laid eyes on Golovanov. But I did not have the opportunity to speak with him.

The second time was after the war. I was on vacation in Moscow. I arrived at the office of General-Polkovnik Shchetchikov on Leningrad Prospect, at the Directorate of the Ministry of Civilian Aviation. I gave him my book that I had written in Latvia as a gift. He asked me, “Will you stay for tea?» We drank tea. Then he said to me, “We will go for a drive now.” But he did not say where we were going. We drove in his car, somewhere on the Volokolamsk Highway, I think. Perhaps I am mistaken, but I recall precisely that we went away from Moscow. We arrived at a courtyard. “Let’s go in.” We climbed up to the second floor. He opened the door. I looked in, and there sat Golovanov. At that time, it turned out, Golovanov was working as the supervisor of the flight-test station of the Civil Aviation Research Institute. We had a conversation. Shchetchikov said, “Aleksandr Yevgen’yevich, I have brought you one of your airmen. He is an author . . ..” We greeted one another and became acquainted. Golovanov asked me, “What do you think – should the history of long-range aviation be written? The time has come. Who should write it?” I said, “I believe that only that person who created and commanded it can write the history of long-range aviation. Who else could write it? I can write only about that which I saw in the regiment.” And Golovanov said, “Khrushchev thinks I should write that he commanded long-range aviation.”

— Khrushchev???

Yes. Golovanov said that Khrushchev wanted it to be written that he, Khrushchev, commanded long-range aviation. This was completely absurd, since Khrushchev had no connection whatsoever with long-range aviation.

And then Golovanov told me this story. “In 1941, they appointed me division commander in place of Vodop’yanov. At this time the division was subordinated to the Supreme High Commander. I sat in his office. Stalin sat behind his desk, with his telephone at his right side. It was a system that allowed me to hear everything. Zhukov called and reported: «Comrade Stalin, the Military Council of Western Front has made a decision regarding the disposition of the front’s forces. . . ” And he reported in greater detail on the locations of the units. Stalin listened to this and said, “Comrade Zhukov. Do you have shovels?” There was a pause. After the pause, “Yes, Comrade Stalin! What kind of shovels?” “Hand them over to the members of the Military Council, so that they can take the shovels and dig themselves graves! Stalin will never leave Moscow!” Golovanov told me about this incident.

After Golovanov’s death, when the question arose about the publication of his book, General-Leytenant Fedorov, who was the chairman of the ADD veterans council, told me that the book needed to be published, but there was resistance from the Central Committee [of the Communist Party] and Ministry of Defense because Golovanov wrote much about Stalin in the book. The book was not published for many years.

Then I met with Taran at a meeting of ADD veterans. We were talking. “Pavel, you are a Twice Hero of the Soviet Union; why are you only a General-Leytenant?” Someone said to me, “You know, fellows, why he is only a General-Leytenant? Because he is Taran! Because he never bow-towed to the bosses.” After the meeting, I said to him: “Pavel, let’s go sit down and talk.” “By all means!” We walked into a restaurant, ordered a bottle of vodka and in the process of drinking it began a conversation. “Pavel, you are aware of this humiliation—they don’t want to publish a book about Golovanov.” “What do you suggest?” “I recommend that you write a letter to the appropriate authorities recommending publication of this book, but it should be signed by Heroes of the Soviet Union.” “Who?” “Well, you should be the first, as a Twice Hero.” And we wrote this letter, and circulated it around. I have saved a copy of it. I further asked him, “You should speak out at a session of the council of veterans and say that this attitude toward Golovanov is disgraceful!” Taran spoke out with very sharp criticism of the leadership of the council of veterans regarding [problems with publishing] this book. I met with Golovanov’s daughters—they thanked us and cried. Since that time, for many years I have known Ol’ga Aleksandrovna Golovanov. The book was finally published.

Golovanov – what kind of a man was he? I think that Novikov [Commander in Chief of the VVS] was not even a close match to him!

Translated to English by James F. Gebhardt